Back in 1967 during the Six-Day War, the USS Liberty, an American technical research ship stationed in the international waters of the Sinai Peninsula, was attacked by Israeli Air Force jets, who killed 34 crew members and wounded 170 more. Controversy surrounded the attack: was it a mistake or a purposeful strike designed to draw America into war against Eygpt?

Nevertheless, the Israeli government subsequently paid out millions of dollars in compensation to the families of the men killed in the attack, as well as money for the wounded and to repair the catastrophic damage to the ship. The incident nearly derailed the relationship between the two allies. Even though it remains a source of controversy forty years later, America accepted Israel’s explanation that the attack on the ship came about due to mistaken identity under the duress and confusion of being at war against its Arab neighbours.

The lesson to draw from this incident is that mistakes happen in war; when huge blunders are committed by vital allies, cover-ups also happen; and that apologies are as powerful a tool as physical weaponry in the modern arsenal of international relations.

Governments have apologised for many of their past mistakes over the last sixty years: Germany apologised over the Holocaust, took full responsibility, and paid reparations to the families of Jews murdered by the Nazis in World War II. The United States paid reparations amounting to $20,000 to each Japanese-American person sent to the Internment camps during the same war. In 2008, the Australian government formally apologised to its indigenous Aboriginal population for its past wrongs, but did not include compensation as part of their apology.

In contrast, the Catholic Church has had a checkered history with apologies to people who suffered sexual abuse at the hands of its priests, apologising for some cases and retracting apologies in others, and Turkey has never officially apologised for the Armenian genocide of 1915.

Political apologies and restitution, when sincere, serve a powerful purpose in government and diplomatic relations. They show contrition and a desire for reconciliation as a means of nation-building. They can show a government’s willingness to distance itself from past policies. They can assuage negative public reaction in reaction to the event in question. And they can normalise relations between two governments or entities in dispute or conflict. (“Apologising For the Past - Does History Matter?”)

On the occasion of America’s 236th Independence Day, America has finally apologised to Pakistan over the attack at the Salala border post, in which NATO forces killed 24 Pakistani soldiers. The attack and the subsequent damage to US-Pakistan relations saw the closing of Nato border supply routes; these routes have been re-opened and Pakistan will not charge transit fees now or in the future.

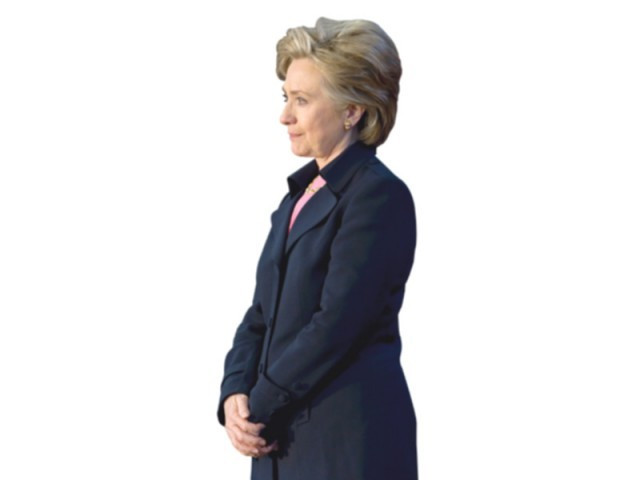

The wording of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s apology holds clues as to the intent of the United States in issuing this apology. She said that she wished to express America’s “deepest regrets” for the Salala incident, and sent “sincere condolences” to the families of those killed in the attack. She said the United States and Pakistan are “committed to working together... in pursuit of shared objectives on the basis of mutual interests and mutual respect.”

These words were not chosen hurriedly or at random; they were agonised over by a team of diplomats, each word carefully selected to show that the United States acknowledges the damage done to the US-Pakistan relationship and wants to get things back on the right track.

Pakistan’s decision to not charge transit fees shows that it has been stung by Leon Panetta’s claims that it shut the Nato supply routes only to wrangle more money out of the United States. This concession has been met with cynical surprise by those who believe a backdoor deal has been cut with the United States that will ensure money reaches the hands of the army in some shape or form. America has matched this concession with one of its own: lethal equipment will not be transported over the supply routes except what is needed to equip the Afghan National Security forces. Compensation to the families of the soldiers killed has not been outlined in the statement; it may well be an under the table deal as well. Yet, this kind of negotiation should not surprise anyone. It may be an undiplomatic thing to admit, but foreign policy is all about a country’s needs and interests; Pakistan and the United States need each other more than they hate each other at this point in time.

The significance of this apology is huge; in international relations, apologies of these types can be interpreted as an admission of guilt. Another reason for exercising care over the wording of apologies is that once offered, they become legal statements, on the basis of which victims can sue for reparations under international law. Already under pressure by the victims of drone attacks in northern Pakistan, the United States would have wanted very badly to avoid a series of high-profile international court cases from the Salala killings.

But instead of looking at the United States’ apology for the attack at Salala as a triumph merely for Pakistan and a humbling of the United States, we Pakistanis should step back and see the bigger picture. As the ruling PPP party has been painting it; the apology means that the relationship between the two countries has been acknowledged and accepted as vitally important to both. It is too important to allow it to be ruined over this incident.

Sincere apology also has a powerful psychological effect on both the offender and the offended person. According to an article in Psychology Today (“The Power of Apology”, Beverly Engel, 2002), apologising for past wrongs promotes emotional healing and allows the offendee to feel that the perceived threat from the offender has been removed. It allows for mutual empathy and the dissipation of anger and sorrow. Finally, it is a humbling process: when you find the courage to admit your wrongs, and work past the resistance to apologise, you are well on the way to developing both self-respect and mutual respect. This is something that the relationship between Pakistan and the US has lacked for a very long time.

Intention and attitude mean everything when governments apologise for a past wrong. When it is truly heartfelt, it can be a life-changing experience for both the apologiser and the one being apologised to. Whether or not the United States has been earnest in its apology and intends to correct its past mistakes can be debated all day and all night (and will be, by everyone in Pakistan), but the truth remains that, saying sorry and making amends is not an admission of weakness, but of strength.

Apology is the only action that can engender true forgiveness between nations. Perhaps for this reason, in the lexicon of diplomatic relations and foreign policy, “sorry” may be the most powerful word of all.

Read more by Bina here or follow her on Twitter @BinaShah

The power of 'sorry'

Is the United States' apology and their making amends an admission of weakness, guilt or strength?

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ