CA Sports was founded in 1958 in Sialkot by Charaghdin Abdulrasheed. The company’s name refers to the first initial of its founder’s name, as well as his son, Abdul. At present, Zahid Javid, Abdul’s son and Charaghdin’s grandson, is at the helm of the company. “CA Sports started out manufacturing wooden tennis rackets,” Javid explains. Graphite rackets were introduced in 1975 and thereafter, the production of traditional lawn tennis rackets declined. By 1978, CA started production of cricket bats and sponsored their first cricketer, Salim Malik.

The finished bat is adorned with the CA Sports logo before it is ready to leave the factory. PHOTOS : SA’ADIA KHAN

Javid says the demand for cricket bats has been on the decline, particularly as the game is not played at club level and fewer children take up the sport at club and regional levels. However, the sales of ‘tape ball cricket bats’ has increased. A ‘tape ball’ is a tennis ball wrapped in electrical tape and used to play street cricket. This kind of cricketing kicked off in Pakistan in the 1980s especially in cities like Karachi, Lahore, Faisalabad, Rawalpindi, Peshawar and Sahiwal. Tape ball cricket has developed into an integral part of the game in Pakistan and the format is played in virtually every sports group or club; pacers such as Shoaib Akhtar and Wasim Akram developed and refined their bowling line and length from the bounce and speed generated by the bounce of the tape ball.

Tape ball bats can vary in length, width and weight as compared with regular cricket bats, and they are more curved. CA produces 40,000 to 45,000 regular bats every year and up to 500,000 tape ball bats. “CA is the pioneer in tape ball bats,” Javid explains. The bats are only sold in Pakistan and Bangladesh and the wood used for these bats comes from Mansehra, Peshawar, Abbotabad and Rawalkot.

The ‘gentleman’s game’

The first references to cricket date back to the 13th century, with historians saying it started out as a children’s game. By the 18th century, the sport gained popularity with the English aristocracy, evolving to be played ‘in a gentleman’s manner’ — with no sledging (insulting or verbally intimidating other players), hostility or bodyline bowling (an aggressive form of bowling pioneered by the English team in the 1932-1933 Ashes tour of Australia).

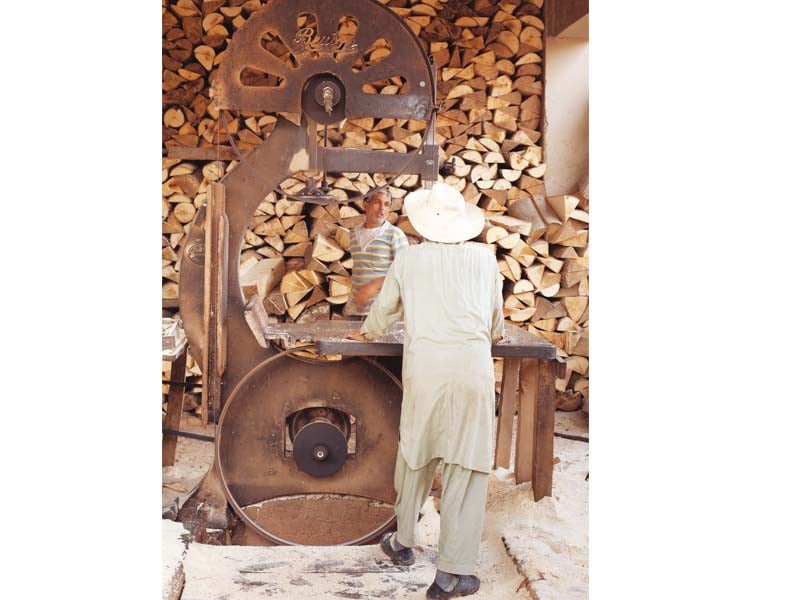

After the willow wood has been dried, a stencil is used to mark the piece of wood for the cleft to be cut out. PHOTOS : SA’ADIA KHAN

In 1771, it was determined that the width of the bat would be 4 ¼ inches, which has remained the measurement since. The oldest bat dates back to 1729 and a bat cannot exceed the length of 38” (965mm) and must weigh anywhere between 2lb 6oz to 3lb 2oz. “Our family has been manufacturing cricket equipment and clothing for three decades now,” says Javid. CA is the official supplier to the Pakistan Cricket Board and sponsors the national cricket team.

Bat-making is historically known as ‘pod shaving’ and traditionally, cricket bats are made from willow wood, specifically from a variety of white willow called ‘cricket bat willow’ or ‘Salix alba var. caerulea’, which is tough yet pliable. This type of willow is cultivated only in England or Kashmir and the trees are usually harvested between the ages of 15 and 20 years. This soft fibrous timber of the willow possesses the perfect characteristics — balance, power and durability — to perform in a cricketing environment due to its stringy wood fibres that give the wood elasticity, the key to its performance.

The narrower the grain — the growth rings of the trunk, which can be seen on the bat’s face — the longer the tree has grown before being harvested. The more grains the better the performance of the bat; a bat with six or more grains is considered to be ‘good’ and 10+ grains means the willow is excellent, Javid explains. The willow used by CA arrives graded and ready to go to production.

Making a bat

Each bat has to be carefully cut with its face along the radius of the tree trunk; a piece three quarters of a metre long is cut and the willow is placed in direct sunlight to dry. A cleft is cut at the top end, where a dried cane handle glued together in sections is carefully inserted and glued into place. This handle is reinforced by binding and coated with an extra layer of rubber glue to prevent the twining from unraveling. The willow wood blade flexes enough to deliver a good hit and the cane handle absorbs that energy protecting the player’s hand.

The cane handle takes shape before it is reinforced with twining. PHOTOS : SA’ADIA KHAN

Once the handle is fitted, a tool called the drawknife shapes the bats. Ghulam Muhammad, one of 500 workers at CA, says that the shape and curve of each bat he lays his hands on is identical — that’s the beauty of his craft. “Skilled craftsmen are used throughout the manufacturing process,” explains Javid. These craftsmen are able to create the exact curvature required for each bat weight and specification.

The workers use tools called metal hand planes to flatten the edges of the willow bats, making sure to strike just the right balance. If the edges are too cured, the blade will not perform well. Then, a pressure machine with a curved roller applies three tonnes of pressure to the bat face and compresses the wood. Finally, the bat is sanded down with an air-filled drum sander and polished against a cotton wheel.

All the bats end up in the hands of Mustafa Ali, a 26-year-old man responsible for the adornment of the bats with the official CA logo. “Each bat is first stamped with the company logo and weighted,” he explains. “Then I put stickers on the bat with information about its weight and so on.”

The craftsmen at CA are seasonal workers and many maintain farms or livestock in down periods.

Eliminating the process of ‘knocking-in’ with a mallet, this machine compresses the bat without changing its initial shape. PHOTOS : SA’ADIA KHAN

Using a mallet — a hammer-like tool — bat-makers would traditionally knock on the bat’s wood and the softer the sound, the softer the wood and therefore, the better the bat will play. At CA Sports, however, as is the case at many sports manufacturing companies, the mallet was left behind years ago. Now, a cricket bat has to withstand three tonnes of pressure applied by a machine with a curved roller that rounds off the bat’s face and compresses the wood up to one centimetre.

CA Sports was founded in 1958 in Sialkot by Charaghdin Abdulrasheed. The company’s name refers to the first initial of its founder’s name, as well as his son, Abdul. At present, Zahid Javid, Abdul’s son and Charaghdin’s grandson, is at the helm of the company. “CA Sports started out manufacturing wooden tennis rackets,” Javid explains. Graphite rackets were introduced in 1975 and thereafter, the production of traditional lawn tennis rackets declined. By 1978, CA started production of cricket bats and sponsored their first cricketer, Salim Malik.

Javid says the demand for cricket bats has been on the decline, particularly as the game is not played at club level and fewer children take up the sport at club and regional levels. However, the sales of ‘tape ball cricket bats’ has increased. A ‘tape ball’ is a tennis ball wrapped in electrical tape and used to play street cricket. This kind of cricketing kicked off in Pakistan in the 1980s especially in cities like Karachi, Lahore, Faisalabad, Rawalpindi, Peshawar and Sahiwal. Tape ball cricket has developed into an integral part of the game in Pakistan and the format is played in virtually every sports group or club; pacers such as Shoaib Akhtar and Wasim Akram developed and refined their bowling line and length from the bounce and speed generated by the bounce of the tape ball.

Tape ball bats can vary in length, width and weight as compared with regular cricket bats, and they are more curved. CA produces 40,000 to 45,000 regular bats every year and up to 500,000 tape ball bats. “CA is the pioneer in tape ball bats,” Javid explains. The bats are only sold in Pakistan and Bangladesh and the wood used for these bats comes from Mansehra, Peshawar, Abbotabad and Rawalkot.

The ‘gentleman’s game’

The first references to cricket date back to the 13th century, with historians saying it started out as a children’s game. By the 18th century, the sport gained popularity with the English aristocracy, evolving to be played ‘in a gentleman’s manner’ — with no sledging (insulting or verbally intimidating other players), hostility or bodyline bowling (an aggressive form of bowling pioneered by the English team in the 1932-1933 Ashes tour of Australia).

In 1771, it was determined that the width of the bat would be 4 ¼ inches, which has remained the measurement since. The oldest bat dates back to 1729 and a bat cannot exceed the length of 38” (965mm) and must weigh anywhere between 2lb 6oz to 3lb 2oz. “Our family has been manufacturing cricket equipment and clothing for three decades now,” says Javid. CA is the official supplier to the Pakistan Cricket Board and sponsors the national cricket team.

Bat-making is historically known as ‘pod shaving’ and traditionally, cricket bats are made from willow wood, specifically from a variety of white willow called ‘cricket bat willow’ or ‘Salix alba var. caerulea’, which is tough yet pliable. This type of willow is cultivated only in England or Kashmir and the trees are usually harvested between the ages of 15 and 20 years. This soft fibrous timber of the willow possesses the perfect characteristics — balance, power and durability — to perform in a cricketing environment due to its stringy wood fibres that give the wood elasticity, the key to its performance.

The narrower the grain — the growth rings of the trunk, which can be seen on the bat’s face — the longer the tree has grown before being harvested. The more grains the better the performance of the bat; a bat with six or more grains is considered to be ‘good’ and 10+ grains means the willow is excellent, Javid explains. The willow used by CA arrives graded and ready to go to production.

Making a bat

Each bat has to be carefully cut with its face along the radius of the tree trunk; a piece three quarters of a metre long is cut and the willow is placed in direct sunlight to dry. A cleft is cut at the top end, where a dried cane handle glued together in sections is carefully inserted and glued into place. This handle is reinforced by binding and coated with an extra layer of rubber glue to prevent the twining from unraveling. The willow wood blade flexes enough to deliver a good hit and the cane handle absorbs that energy protecting the player’s hand.

Once the handle is fitted, a tool called the drawknife shapes the bats. Ghulam Muhammad, one of 500 workers at CA, says that the shape and curve of each bat he lays his hands on is identical — that’s the beauty of his craft. “Skilled craftsmen are used throughout the manufacturing process,” explains Javid. These craftsmen are able to create the exact curvature required for each bat weight and specification.

The workers use tools called metal hand planes to flatten the edges of the willow bats, making sure to strike just the right balance. If the edges are too cured, the blade will not perform well. Then, a pressure machine with a curved roller applies three tonnes of pressure to the bat face and compresses the wood. Finally, the bat is sanded down with an air-filled drum sander and polished against a cotton wheel.

All the bats end up in the hands of Mustafa Ali, a 26-year-old man responsible for the adornment of the bats with the official CA logo. “Each bat is first stamped with the company logo and weighted,” he explains. “Then I put stickers on the bat with information about its weight and so on.”

The craftsmen at CA are seasonal workers and many maintain farms or livestock in down periods.

The market

Javid fears that cricket is losing its appeal with the younger generation in Pakistan. Additionally, the manufacturing market has been greatly impacted by the exile of the sport to the United Arab Emirates after the attack on Sri Lankan cricketers in Pakistan in 2009. “Our cricket team needs to [play at] home,” Javid says.

He says business was also affected in the lead-up to the 2015 Cricket World Cup (CWC) as a black market selling clothing and kits thrived. “Even though we are the official manufacturer and distributor of the 2015 CWC goods, it has had little to no impact on accelerating CA Sports’ growth,” he points out. Exports of cricketing goods rose by 15% during the World Cup period and Pakistan earns roughly Rs3 billion annually from total exports of cricket goods.

Cricketing vernacular

Blade: The main body of a cricket bat is called the blade. It is generally flat on the striking face and with a ridge on the reverse (back) which concentrates wood in the middle where the ball is generally hit. Some cricket bat blades are covered with hard plastic to protect the wooden surface from wear and tear.

Sweet spot: The centre of the blade is known as the sweet spot, although batsmen will use different parts of the blade to play different shots.

Handle: The blade is connected to a long cylindrical cane handle, similar to that of a tennis racquet, by means of a splice. The handle is usually covered with a rubber grip and made from white willow wood or cane, bound with fine twine to further enhance grip.

Shoulders and toes: The top part of a cricket bat closest to the handle is called the shoulder. The toe of the bat is the bottom of the blade and the part of the bat that rests on the ground as the batsman waits to hit the ball.

Sa’adia Khan is a freelance photographer based in Islamabad. She tweets @IM_SaadiaKhan

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, March 29th, 2015.

Javid fears that cricket is losing its appeal with the younger generation in Pakistan. Additionally, the manufacturing market has been greatly impacted by the exile of the sport to the United Arab Emirates after the attack on Sri Lankan cricketers in Pakistan in 2009. “Our cricket team needs to [play at] home,” Javid says.

He says business was also affected in the lead-up to the 2015 Cricket World Cup (CWC) as a black market selling clothing and kits thrived. “Even though we are the official manufacturer and distributor of the 2015 CWC goods, it has had little to no impact on accelerating CA Sports’ growth,” he points out. Exports of cricketing goods rose by 15% during the World Cup period and Pakistan earns roughly Rs3 billion annually from total exports of cricket goods.

Cricketing vernacular

Blade: The main body of a cricket bat is called the blade. It is generally flat on the striking face and with a ridge on the reverse (back) which concentrates wood in the middle where the ball is generally hit. Some cricket bat blades are covered with hard plastic to protect the wooden surface from wear and tear.

Sweet spot: The centre of the blade is known as the sweet spot, although batsmen will use different parts of the blade to play different shots.

Handle: The blade is connected to a long cylindrical cane handle, similar to that of a tennis racquet, by means of a splice. The handle is usually covered with a rubber grip and made from white willow wood or cane, bound with fine twine to further enhance grip.

Shoulders and toes: The top part of a cricket bat closest to the handle is called the shoulder. The toe of the bat is the bottom of the blade and the part of the bat that rests on the ground as the batsman waits to hit the ball.

A guide to willow grading

Grade 1+ willow — This is the best willow that money can buy. The blade is unbleached with eight to 12 straight grains and is blemish-free to a large extent. Full-sized blade: over £350 (over Rs53,282)

Junior blade: over £150 (over Rs22,835)

Grade 1 willow — This is high quality unbleached English willow. It has a slightly broader grain and sometimes a slight red edge.

Full-sized blade: £250 — £300 (Rs38,046 — Rs45,670)

Junior blade: £120 — £150 (Rs18,268 — Rs22,835)

Grade 2 willow — This is unbleached English willow with some minor blemishes, red wood on the edge and a slight irregular grain.

Full-sized blade: £200 — £250 (Rs30,448 — Rs38,046)

Junior blade: £100 — £120 (Rs15,223 — Rs18,268)

Grade 3 willow — Some of these bats will be bleached English willow to cover up a more irregular grain and more blemishes.

Full-sized blade: £150 — £200 (Rs22,835 — Rs30,448)

Junior blade: £75 — £100 (Rs11,418 — Rs15,223)

Grade 4 willow — This will be bleached English willow which is often covered up with a protective facing and sold as ‘non oil’.

Full-sized blade: £100 — £150 (Rs15,223 — Rs22,835)

Junior blade: £50 — £75 (Rs7,612 — Rs11,418)

Source: Talent Cricket

Sa’adia Khan is a freelance photographer based in Islamabad. She tweets @IM_SaadiaKhan

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, March 29th, 2015.

1713904359-0/burn-(1)1713904359-0-270x192.webp)

1713853507-0/MalalaHilary-(2)1713853507-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ