Teaching in English may harm your child’s future

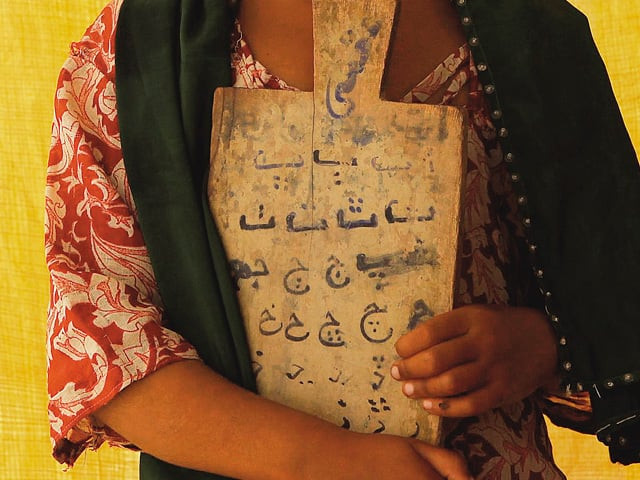

Teaching in an unfamiliar language can also cause alienation between home and school.

University of Leeds UK Honorary Senior Research Fellow, Hywel Coleman, explained that teaching in an unfamiliar language can also cause alienation between home and school, poor educational achievement, poor acquisition of foreign languages, such as English, ethnic marginalisation and long-term decline of indigenous languages.

Coleman was quoting his report during a lecture, which was part of the policy dialogue organised by the British Council and the Society of Pakistan English Language Teachers (Spelt) to discuss 'Language in Education in Pakistan' at the Department of English, University of Karachi, on Wednesday.

Dream policy for Pakistan

In his report on the dream policy for Pakistan, Coleman has suggested that the child's first language should be the medium of instruction up till class III, Urdu should be the medium till class IX and English should only be used as a mode of teaching from class X and beyond. Through this scheme, he proposes a bilingual face to education.

However, not all participants at the seminar agreed with Coleman's model. Prof Fauzia Shamim, Department of English, believed that bilingual education in Pakistan will be hindered by a lack of materials in vernacular languages, limited support for high quality language instruction and the "ambivalent" attitude towards the value of vernacular languages.

Shamim pointed out that in the presence of more than 70 spoken languages, it will be difficult to identify major languages of instruction. English is "a tool for individual and national development" and it can only be acquired easily if it is learnt in the early years, she said, supporting her argument with the example of India and South Africa, where such policies failed.

On the other hand, Dr M Memon, professor and director of the Institute of Educational Development at Aga Khan University supported Coleman's model.

"I studied in Urdu till Intermediate and still managed to learn English later," he said. Making English the teaching language may work for people whose families also speak it but those from poor socio-economic backgrounds, whose native language is the home language, may have to struggle to express and think in one language, he explained.

Dr Hina Kazmi supported the use of English by saying that none of the native languages, including Urdu, have the literature, research, translations and terminology of modern scientific advancements to become teaching languages.

English in Pakistan is seen as a language to help you progress in your studies as well as jobs, said Spelt programme committee coordinator Fatima Shahabuddin. According to the language policy of 2009, English has been made compulsory for primary classes, Shahabuddin said, stressing that there is a dire need to produce English language teachers.

Meanwhile, Tony Capstick, English adviser at the British Council referred to the role of his organisation in the education sector. "Having commissioned Coleman to carry out extensive research across Pakistan, we felt that it was important to use this as a starting point to consultation [on education]," he said.

Research cited by the researcher

According to Coleman, there are more than 70 languages spoken in Pakistan with over a million people speaking each of the six major regional languages. Urdu is the first language of only seven per cent of the population but spoken by the greatest number of people.

In his research, Coleman divided the schools in Pakistan into four types: private elite (English medium), private non-elite (nominally English), government (Urdu) and madrassas (Urdu). Since around 95 per cent children in Pakistan do not study in their home language, their results are poor, except for children attending private, elite schools.

In conclusion, the foremost priority is to contribute to bilingual education through policy debates and raising awareness on the importance of mother-tongue education in the early years of schooling, Coleman said.

Published in The Express Tribune, October 14th, 2010.

1724319076-0/Untitled-design-(5)1724319076-0-208x130.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ