The art archive: Sublime feeling

There is a way in which sublime feeling no longer fits with contemporary visual experience.

There is a way in which sublime feeling no longer fits with contemporary visual experience. This may be especially true for big city life. A landscape established by human density (ethnoscapes) — or a great visual vitality borne of multiplicity, juxtaposition, occasional excrement — it has in its bombast simply no time for the solitary refinements of the sublime. Or so it seems.

We use the word at leisure. In colloquial terms ‘sublime’ is used synonymously with ‘great’. We acknowledge at first a sensory experience, a rare savour, almost noble, almost divine (another colloquialism), a refined, ingested pleasure in the absence of theistic experience.

This re-placed idea, from sacred to secular, has a history of evolution in the field of aesthetics over two centuries long. It has been foundational to the idea of western art, both in the sense of creation and in the sense of its value and appreciation. According to theorist Paul Crowther, the ‘legitimising discourse of art’ is based on the idea that an art object is something whose meditation elevates one’s self, expands one’s consciousness through insight, has positive effects via a contrary affective mode we may call ‘the sublime’.

Greek rhetorician, Longinus, first coined the term (first century AD) in order to think through the tools of persuasion for public speech. Influenced by early Christianity, Longinus was trying to get at a certain kind of rapture, inherent to language, but sourced in that grandeur of spirit which is not of this world. This other-worldliness, elsewhere-ness, and passage into its ecstasies, was later taken up by Edmund Burke, Immanuel Kant during the 18th century, and by derivation, Jean-Francois Lyotard in the 20th. In each case, intellectual effort has been applied to demystify the transcendent function of the sublime — that is, the frightening and pleasurable crossing from this to that world. Or at least such has been the attempt.

With Lyotard, a French postmodernist thinker, ‘that world’ comes to an end in the idea of indeterminacy. If sublime experience, and by extension the sublime aesthetic, is to have contemporary relevance, it must occur in the here and now. This shift brings up two concerns. The first is an inclusion of all things injured, defective, monstrous even, a particular description of human form. And the second implies the acknowledgment of an intrepid blind spot or absence.

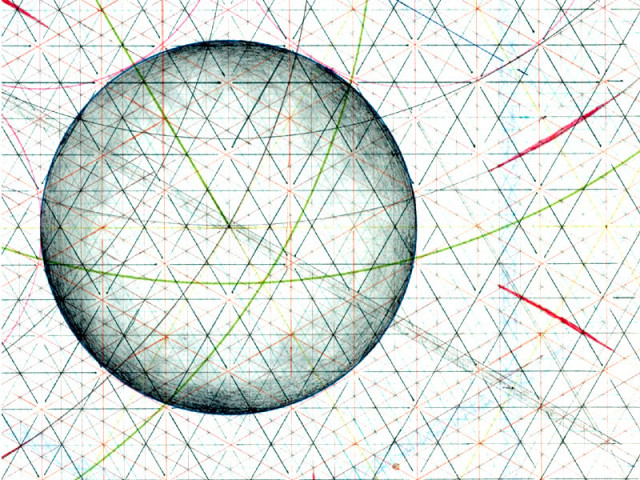

Following Lyotard’s trajectory, for western art this meant a thinkable evolution from awe-inspired Romantic landscapes (the key site of sublime intercourse) to avant-garde or modernist experimentation. It implied an organic movement from principles of mimetic art, or art as a window to, in commemoration of visible reality, to the impetus for genres such as minimalism and abstraction. At the core of Lyotard’s persuasion rests the notion that we live in an age of indeterminacy. Alongside a deformation of classical aesthetic values (reference, perspective, dimensionality etc) the witnessing and registering of that which is unknown forms a key aspect of art practice. It is, in his words, the energy of the ‘inexpressible’ or the ‘non-presentable’ which frames the broadest gestures of modern art. Lyotard is thinking about the power of abstract art in particular.

This backdrop has perhaps curious relevance for art production in Pakistan. It may provide a lens for considering art education, practice, and reception, especially within an urban context. One may add to this a cultural milieu ethically questioned by aniconic religious-aesthetic doctrine, and, wherein ideas of sublimity and beauty are not deemed oppositional categories but cohere within the singular aspirational term ‘jalal’.

A sympathetic congress of ideas may be found in contemporary non-figurative art and in the work of women artists in particular. Here, I am thinking of a multigenerational exploration, an aesthetic where the lines of figurative and abstract expression have been blurred or crossed over by its practitioners in the course of their painting. Meher Afroz, Nahid Raza and Mussarat Mirza immediately come to mind, as do Lalarukh, Naiza H Khan, Ayesha Qureshi, as well as Shahzia Sikander’s work with geometric abstraction. The question of a sublime aesthetic and its relationship to the feminine may be usefully unravelled, despite distinct concerns and distinctly separable practice in the latter selection of artists. I am thinking of a powerful gallery of images, and an extended essay that allows for such meditation.

Published in The Express Tribune, May 12th, 2012.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ