Praise did not come easily to Shaikh Ayaz — the grand doyen of Sindhi literature and a one-time contender for the Nobel Prize. He wrote fiery polemics against his contemporaries and critics in retaliation. Through his essays, he managed to settle old scores and even flared up a few others.

But even he was unable to withhold his praise for Attiya Dawood’s poetry. She was never made a target of ridicule. On the contrary, he reserved for her the best compliment she could be given. Each and every poem, Ayaz wrote, “is lustrous like a pearl”.

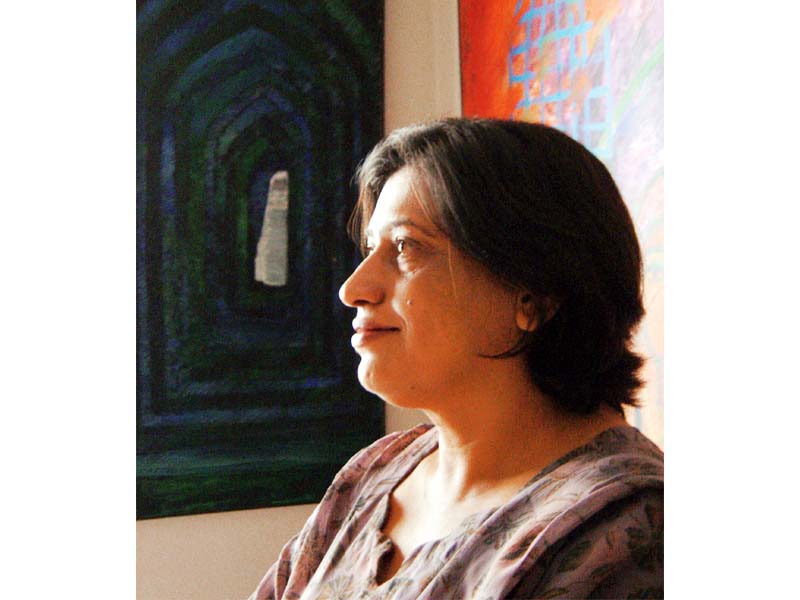

For nearly four decades now, Dawood has ensured that the hyperbole of Ayaz’s compliment reaches appropriate justification. She has firmly consolidated her image as a Sindhi and Urdu writer.

However, the journey has not been an easy one. Some of the metaphors that are synonymous with Dawood’s work are the product of a torturous journey of self-discovery. She has written about “frantic fingers which undo a tattered chaddar wrapped around the head” and “hands reaching for the door-latch of a cage kept in a man’s courtyard”. But every word she has written came at a personal cost — an undeniably painful one.

When she was first published in 1980, she found herself at the receiving end of tremendous hostility from her brother. Born into a conservative family in Moladino Larik, a small village in Sindh, Dawood struggled to break through the shackles of a narrow-minded society that deprived her of the opportunity to discover her own identity. She once wrote that her childhood milieu was built “on the skulls of what were [her] ambitions”.

Dawood recalls her first visit to a millstone in her village.

“I was only six years old,” she says. “I went there to grind five kilogrammes of wheat. It was a task reserved for men only because the millstone was far from home. No girl had dared to flout accepted norms and go to the millstone. But I did it anyway and felt great.”

Unfortunately, the inner courtyard was not the only sphere where Dawood had to face criticism. Her first anthology attracted a morass of angry letters from readers. At the same time, Dawood’s work brought her into the limelight as a fearless voice from the subcontinent.

Dawood now lives in Karachi with her husband and two daughters in a sunny apartment that faces the sea. Memories of her blinkered childhood in a small village are distant and unthreatening. She has sheltered her daughters from the turmoil she faced as a child. Unlike their mother, Dawood’s daughters do not have to reach for door-latches to find their quotient of happiness.

The writer is a student at the Institute of Business Administration and takes an interest in English, Urdu and Sindhi literature.

Published in The Express Tribune, October 4th, 2015.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

1722586547-0/Untitled-design-(73)1722586547-0-165x106.webp)

1732326457-0/prime-(1)1732326457-0-165x106.webp)

1732308855-0/17-Lede-(Image)1732308855-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ