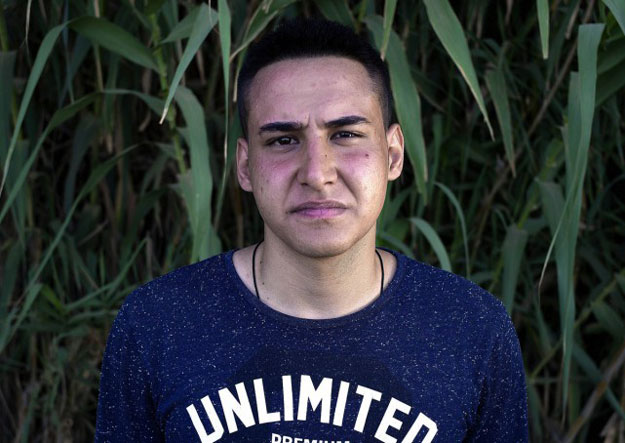

Ahmadi looks no different from other Afghan kids betting their futures on new lives in the European Union: he wears jeans and a t-shirt, and his backpack carries all his worldly possessions.

But as he and his friends trudge up from the shore of Lesbos island -- their first European steps in a journey that is far from over -- it's obvious this gawky teenager is a little out of the ordinary.

The first sign is an almost obsessive love of languages that has given him a startling ability to jabber away in rapid English, French or German.

Read: Walls and violence will not solve migrant crisis - EU Commissioner

Then there is the sheer scale of his ambitions. Ahmadi wants to become an inventor -- "like the Japanese who invented robots" -- in order, he says, to show "appreciation for what the Europeans will do for us".

Top of his to-do list: designing a new drone to detect and destroy explosives. A device that could have saved the friend he lost in a car bombing.

"I know that sometimes when you are small, people are not going to take you seriously," Ahmadi tells AFP, his own young face deadly serious.

"I need to learn a bit more about programming and designing the device. If I go to Germany and someone helps me, it will take me between six months and one year."

Ahmadi loves the idea of Germany. For him, there is no limit to what he will be able to do if his asylum application is accepted there.

"The thing I love about Germans," he says, "is they respect your talent and they believe in you."

Ahmadi is hoping his love of learning will go down better in Germany than it did in Herat, western Afghanistan.

The son of a dairy worker, he had polished his English chatting to American soldiers, despite his mother's worries they would teach him how to smoke.

Two years ago he began giving informal lessons to younger kids in his bedroom -- basic computer skills, painting, and his beloved languages. "I wanted to share what I know. I didn't charge them -- I could see the ray of hope in their eyes. That was enough for me."

Then, he says, local Taliban militants heard what he was doing.

"They told us, 'You're infidels because you're teaching the kids foreign languages,'" says Ahmadi, his voice shaking with bitterness. "They told me they would stone my sister and mother because of me."

It is one of two times during the teenager's long conversation with AFP that he appears close to tears.

The other is when he talks about the chubby little brother -- so fond of learning the English words for foods -- whom he misses so much.

Ahmadi says he shut down his "classroom" in late 2014, his family terrified by Taliban death threats. It was then that he made up his mind to head to Europe. The rest of the family has stayed behind.

Ahmadi left Afghanistan more than 50 days ago, an odyssey that has seen him get beaten by Iranian border guards, walk at one point for 24 hours straight, and work in a supermarket in Turkey for a month to save up "for a rainy day".

Read: Chief of Germany's besieged migrant office resigns

In his more cheerful moments, Ahmadi speaks with the optimism of someone who knows they are bright and determined enough to have a promising future.

For some, he is exactly the kind of youngster who could turn Europe's refugee crisis into an opportunity rather than a burden. Germany's central bank chief said Wednesday the influx of workers could be just what the country needs to maintain its status as the EU's powerhouse.

But when Ahmadi talks about why he left, how difficult and dangerous this journey has been and how easily his "German dream" could slip through his fingers, he looks exhausted.

"This trip gets you old," he says suddenly.

Ahmadi worries incessantly about whether his asylum claim will be accepted and that, even if it is, he won't fit in.

Ahmadi likes Western pop music -- Taylor Swift and Katy Perry -- but most of what he knows about Germany comes from history books.

One thing he is aware of is that while Germany is set to take in up to a million refugees and migrants this year, not everyone is welcoming them.

"We are the new guys," he says. "We are coming from new cultures, new traditions. And it will absolutely make a lot of problems for the local guys, whether you are in Germany, whether you are in France.

"If they like us, I understand them. If they do not like us I understand them better, because they have every right to feel threatened by the presence of the foreigners."

Ahmadi has vowed one day to write a book about this journey.

"Everything is in here," he says, tapping his head. "It is the story of a young kid who starts his journey from his own country in order to get to Europe.

"It is the memory of a group of people who are escaping from pain."

1719660634-1/BeFunky-collage-nicole-(1)1719660634-1-405x300.webp)

1732276540-0/kim-(10)1732276540-0-165x106.webp)

1732274008-0/Ariana-Grande-and-Kristin-Chenoweth-(1)1732274008-0-165x106.webp)

1732273396-0/Copy-of-Untitled-(72)1732273396-0-270x192.webp)

1732269802-0/Copy-of-Untitled-(71)1732269802-0-270x192.webp)

1732261957-1/Copy-of-Untitled-(66)1732261957-1-270x192.webp)

1732258132-0/BeFunk_§_]__-(26)1732258132-0.jpg)

COMMENTS (2)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ