This wish would make his mother, Raisa, unhappy. "If you go into the army, you'll be away from us and won't take care of us when we are old," she would tell him.

Farooq gave up his wish and did not join the armed forces. Yet for most of his life, he was forced to stay away from his parents.

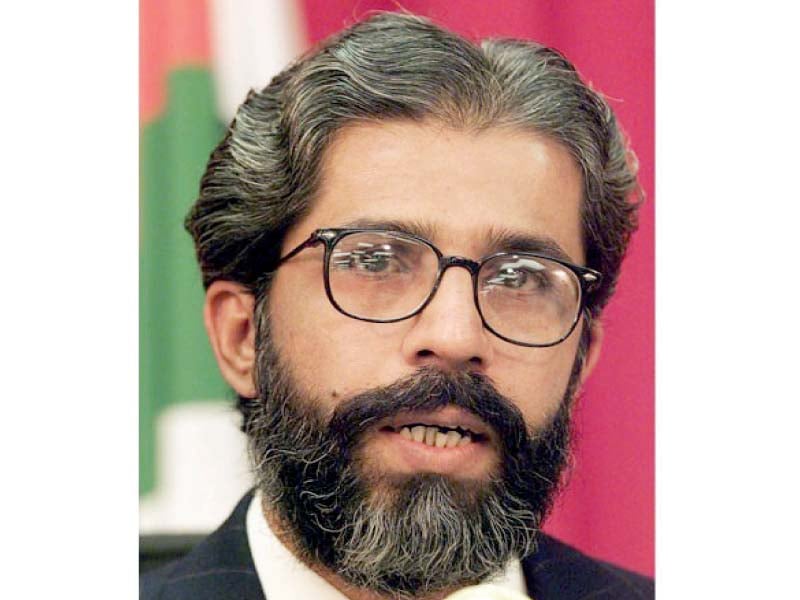

The slain leader of the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) was stabbed five years ago — September 16, 2010 — near his home in London, after he went into hiding during the 1992 operation against the party and resurfaced many years later in the UK, where he lived in exile until his death.

His family marked the death anniversary at their house in Sharifabad on Wednesday. There was a tent erected outside the house, where women read the Holy Quran and prayed on beads. Inside, his mother sat in the drawing room with red walls, which carried a smiling picture of Farooq. A bag of rose petals was also kept aside for the men to spread over his grave later.

Read: 5th death anniversary: Scotland Yard renews pledge to arrest Dr Imran Farooq’s killers

The grieving mother has faith that her son's killers will be traced. "I have trust in Allah and I have confidence in the Scotland Yard," she told The Express Tribune. "They'll arrest whoever was involved."

With some murder suspects in the custody of the local authorities and suspicion falling on the MQM being involved in the murder, Raisa said she suspects no one. She recalled how her son shared the same sentiments.

Farooq, who was a close aide of MQM chief Altaf Hussain and was the party's only convener, claimed he never felt threatened by anyone, even when he severed ties with the MQM four years before his death. "This is London. Nothing will happen to me here," he would tell his family.

Born in Liaquatabad in 1960 as the third of nine siblings, Farooq studied at Anjuman School. His mother was so keen for him to finish school that there was a time when he attended class four in the morning and took class five lessons at another school in the afternoon.

As a child, he liked to wear white clothes. He would put the Pakistani flag outside his window every morning and put it away at night. He always paid attention to his appearance and would never step out of the house without his hair brushed, Raisa remembered.

Farooq was a book lover and was an ardent fan of Ibne-Safi's detective novels, Imran Series, the digest Sab Rang, and the writings of Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Saadat Hasan Manto.

On his mother's wish, he decided to become a doctor. It was during medical school that he joined the student wing of the MQM, the All Pakistan Mohajir Student's Organisation, even though the family opposed the decision. "I told him not to join because his studies would get affected," said Raisa. "His father also told him that politics was dirty."

However, the young and passionate Farooq did not listen. "This is not politics. This is a tehreek, a struggle," he would respond.

Read: People may have helped murder Imran Farooq 'unwittingly': Met Police

During the operation in the 1990s, he went into hiding for seven years. "I didn't meet him for seven years but I would pray for him all the time," said the mother. "He didn't leave for London as the rest of them did. He stayed behind with the workers and didn't abandon anyone. Workers were everything to him. The party was everything."

Choosing not to delve deep into Farooq's political career, Raisa does recall how her husband and other relatives were tortured by the authorities to give details about his whereabouts. "The operation back then was a different one than today's," she said. "The Rangers are doing a good job today by arresting criminals and not harassing their families. Back then, it was different."

Farooq's commitment to the party was reflected when instead of his mother, the party chief chose his bride, Shumaila. His widow and their two sons continue to live in London after his death.

"I met him in London when he was there," said Raisa. "I would cook for him every day. He liked ghobi qeema." Outsiders would consider Farooq to be a reserved person but Raisa remembers him always joking around with the family. She said her son did not want to spend his entire life in London and wished to return home. But his passport was with the authorities since he applied for asylum, she said.

When he did come back to his home country upon his death, Raisa was unable to see him. "We didn't see the body," she sobbed. "We were told it was in a bad shape. But I feel he is with me, here all the time, smiling at me."

Published in The Express Tribune, September 17th, 2015.

1732437695-0/drake-and-charles-(1)1732437695-0-165x106.webp)

1732434981-0/BeFunky-collage-(10)1732434981-0-165x106.webp)

COMMENTS (3)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ