Unintended consequences of medication

It’s a devastating diagnosis because there is no easy cure to stop the body’s joints from weakening. It turns out that Osteoarthritis is the side-effect of a pill Afshan began taking a few months ago, after she returned from Umrah. If only Afshan had known the possible dangers of taking the pill, she might not have taken it; or might have taken a substitute. But she didn’t know and, in fact, had no way of knowing.

The name of the pill she took is Primolut-N. It is used to regulate menstruation, said her doctor, Shazia Tahir. “Most doctors do not make the effort to inform their patients of a medicine’s side effects that sometimes occur in the long term,” she said adding that, “the pill works on the female hormone and its effects varied from person to person.” This problem of ‘not knowing’ is not unheard of. An overwhelming majority of people use traditional medicine or medicine that has dangerous side-effects to cater to their health needs but the safety and efficacy of these medicines is not something that is told to patients.

Perhaps the biggest problem is a lack of time and a desire for efficiency – at the cost of patients health. Busy doctors spend a very small amount of time with each patient and do not have the time to discuss the side-effects. “The medical profession has now largely become a business , doctors do not try to understand how the medicine they prescribe could have a possibly adverse affect,” says Dr Tahir. She adds that they did not spend enough time determining what caused these symptoms.

Dr Tahir says that patients avoid follow-up visits to doctors once they think they are cured. This makes it difficult for doctors to monitor their patients’ reaction to the medication – especially reactions that may not be immediate and that only show up over time. Drugs that commonly cause adverse reactions include antibiotics, anti-neoplastics, anti-coagulants, cardiovascular drugs, hypoglycemic, antihypertensives and CNS drugs.

Consistent use of drugs to control high blood pressure can result in a gradual drop in haemoglobin levels and lead to fluctuations in weight. Other side-effects of medicines also include skin problems that most doctors also often ignore. “Even commonly prescribed painkillers such as Aspirin can have side-effects. They can cause ulcers,” adds Dr Amir Raza Abidi, Secretary General of the Pakistan Medical Association.

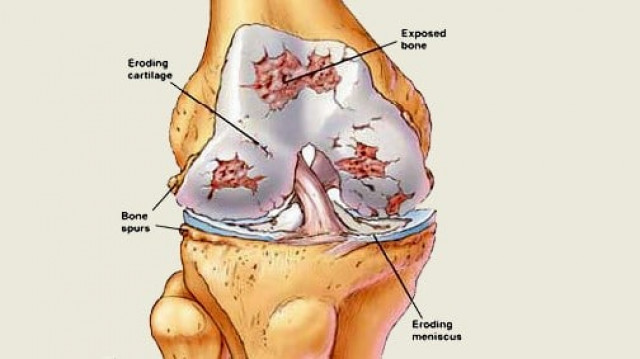

Similarly, cortisone injections – a steroid used to treat inflammation – may not have the same effect on a patient if used after regular intervals because his body becomes resistant to the drug. Once the effect of a regular dose wears off, doctors increase the dosage without informing the patient of its adverse effects. This can be dangerous as multiple steroid injections can lead to weakening of bones.

Dr Javed Rashid of Schering- Plough Pakistan, a medical research company, conducted a study on adverse drug reactions in Pakistan. He highlighted that Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR) account for five per cent of acute medical emergencies and is the 4th to 6th leading cause of death among hospitalised patients across the country, a staggering figure.

These reactions can be both mild and severe and vary from person to person. “Some effects are related to abnormal interaction between the patient and drug and some are dose-related effects that can be toxic in nature. Other side-effects are associated with longterm use of a certain drug or a sudden withdrawal as well,” says his research.

Unethical practices

Experts say that adverse drug reactions can be prevented if doctors play their role responsibly. It is common knowledge that there are certain medicines doctors push because various national and multinational pharmaceutical firms sponsor them. Some doctors are even taken abroad to attend workshops – all on the pharmaceutical company’s payroll.

“Yes we do take doctors (abroad) because this educational exercise is essential and they don’t get these opportunities or support in Pakistan. They need to keep themselves updated. But this does not mean we pressure them to promote our drugs,” says Maria E. Rizvi, Manager Regulatory Affairs Getz Pharma Limited. Dr Maqbool Jafary, who has served in the pharmaceutical industry for 32 years, says that this practice is difficult to monitor owing to the poor implementation of the Drug Act 1976 and the Ministry of Health’s disinterest in monitoring the use of drugs that are known to have adverse effects.

“There is also an unwritten code of ethics that doctors are supposed to follow,” says Dr Jafary. “One of them is respecting the autonomy of the patient, under which the doctor is liable to take consent before prescribing a certain drug. But that obviously isn’t happening because most of the doctors, especially in neighbourhood clinics, do not spend enough time with their patients to explain the effect of each drug prescribed.”

Though doctors make an easy target, this issue is further complicated by the fact that most patients are illiterate. This means that they are unable to refer to the information leaflet that comes with the medicine pack and are forced to rely solely on the doctor’s word.

In such a scenario, Maria Rizvi suggests establishing independent drug information services at hospitals that can inform patients of the side effects prior to dispensing medicine. Currently, such a facility only exists at the Aga Khan University Hospital and the Jinnah Post-Graduate Medical Center. In the final analysis, the problem comes down to accountability. Until and unless someone – the Ministry of Health surely – holds manufacturers and doctors responsible, tragic cases like Afshan’s will continue to happen.

*Name changed to protect identity.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ