Afghans in Pakistan: Their home and heart belong here

Many Afghan families living in Karachi are unable to explain the hostility with which they are looked upon

Many Afghan families living in Karachi’s neighbourhoods are unable to explain the hostility with which they are looked upon. Even though their second generation has put down roots here, they are still not considered Pakistani. “In any other country, we would be citizens,” laments Abdul Haleem, a young scarf seller who lives in what is known as the Afghan Basti of Karachi.

Raheemullah, now 50, arrived as a single man in 1979 after he lost members of his family due to war. He got hitched in Karachi and all his eight children were born here. But now people like him and Abdul Haleem fear for their future. They feel they are being targeted as the country reels from last December’s deadly assault on the Peshawar Army Public School.

Last month, a group of girls, clad in white, condemned the December 16 attack during a presentation in a Sohrab Goth seminary, and then on cue from their teacher, joined boy students in singing the national anthem. The words “Pak Sar Zameen…” came out effortlessly. They sang with fervour and ended the anthem by bowing their heads in respect. For these children, Pakistan is the only home they know.

At the Jamaluddin Afghani school, the only one in the locality, girls

furiously scribble out answers for a chemistry paper in a room without chairs or tables. There is moaning over their fate – in fact, they are only too happy to get a chance to study. Most of them know they wouldn’t have gotten such an opportunity in Afghanistan.

So when their loyalty is questioned, they feel insecure and hurt. “We will forever remain grateful and obliged to Pakistan. But Pakistanis should trust us. We will never harm them,” says Haji Abdullah Shah Bukhari, a representative of the refugees.

Many insist that they are not a burden on Pakistan because they earn a living through their businesses, which vary from carpets to garments, leather and threads.

According to the Afghan Consulate’s Refugees and Prisoners section, there are more than 66,700 registered Afghan refugees in Karachi in addition to the 250,000 unregistered ones.

But things are changing fast. There are growing complains about raids, arrests and ill-treatment by law enforcement agencies.

Inside Al-Asif Square at Sohrab Goth, notorious in its heyday for weapons and drugs, the market buzzes with activity. Shops here are stacked with garments, electronics and footwear, while roadside hotels attract customers with their green tea and traditional Afghani pulao.

Elders complain about the raids. “Since the attack, police officers have been picking up men even those with proper registration cards. They release them only after bribes ranging from Rs5,000 to Rs 10,0000,” one man pointed out. In January, up to 25 people were caught. By the first week of February, however, the number of arrests rose. Some 500 men were arrested from Afghan localities by the police. All of them had legal documents.

“This is hurting us. We are poor people, and we are now afraid to leave our homes fearing that we might be arrested,” said another.

Youngsters like Abdul Haleem who were born in Karachi, see no reason why they should be made to go back. “I was born and raised here. I went to school here. I have never been to Afghanistan. I am a Pakistani.”

Where Haleem lives and works, around 3,750 Afghan families mostly from places as diverse as Kunduz, Mazar-e-Sharif and Kabul, are settled. The locality, which is known different names like Jadeed Camp, Afghan Basti or Afghan Muhajir camp is located on the outskirts of Karachi. Since 1986, it is the only official camp for the refugees in the province.

People live in pitiable conditions: mud houses without power or gas, and water supply only recently installed in some parts, the colorful chadars on the doors hide the poverty within.

Rosy-cheeked girls and boys run in the garbage-strewn and sewage-filled lanes, half-dressed. But most aren’t complaining.

Purdah is strictly observed and women and girls venture outside in blue-colored “shuttlecock” burqas. Urdu is not spoken. In one such house, Resa Gul and her two daughters are busy weaving a brown and white rug. “It is difficult work and takes ten days to make one,” she speaks in Dari, as her husband, who works in a factory, translates for her.

Resa Gul’s daughters have few options when it comes to education. Course Wahadat School is one school in this locality but students from grade 1 to 6, study under a thatched roof and sit on broken chairs. There is no government here either.

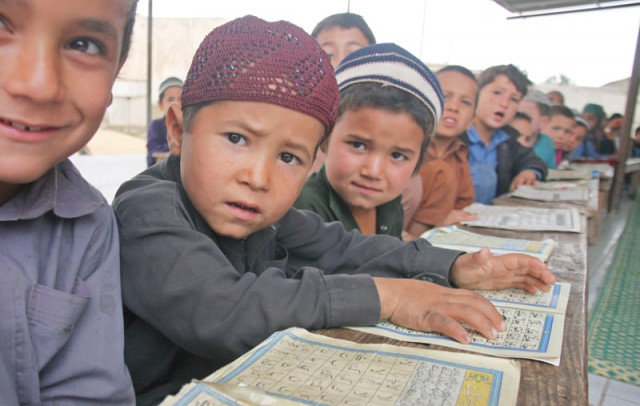

People here say that there are 36 mosques and madrassas impart education, nothing else as in the absence of formal schools, this is where many children go. At the Umer Farooq madrassa, boys sit cross-legged reading verses of the Holy Quran. Their teacher, Raheemullah, says that this is not where extremism is taught.

It is funded by children, whose families pay Rs100 for every child taught per month.

But the seminaries have come under observation as officers from the police’s special branch have started inquiring about what is taught here.

At another madrassa where 400 children study, Qari Faizur Rehman Madani asks why would they support terrorism when they themselves have been its worst victims. “They don’t want to go back.” Madani adds.

Seventy-year-old Haji Zia originally from Kunduz came here in the 1980s. He has not gone back ever since. “My wife and daughters make threads and I sell them. What will I do there?” asks Zia, showing his warehouse stocked with raw cotton for yarn and threads.

The few relatives that returned to Afghanistan have recounted stories of lawlessness and uncertainty. “At least we are safe here,” Zia says. His statement may sound ironic to most Karachi residents. But Zia swears by it.

Published in The Express Tribune, March 2nd, 2015.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ