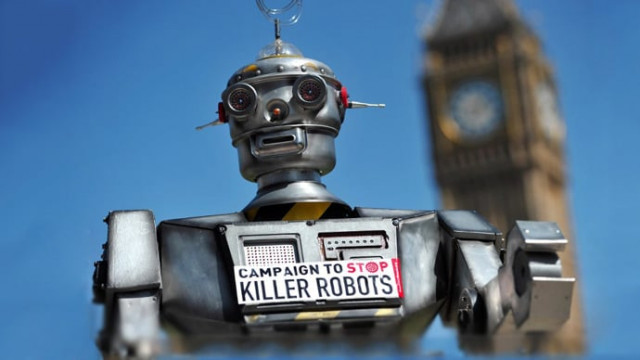

UN talks take aim at 'killer robots'

"I urge delegates to take bold action," said Michael Moeller, head of the UN's Conference on Disarmament.

"The central issue is the potential absence of human control over the critical functions of identifying and attacking targets, including human targets," said Kathleen Lawand, head of the ICRC's arms unit. PHOTO: AFP

That dark vision could all too easily shift from science fiction to fact, with disastrous consequences for the human race, unless such weapons are banned before they leap from the drawing board to the arsenal, campaigners warn.

On Tuesday, governments began the first-ever talks exclusively on so-called "lethal autonomous weapons systems", though opponents prefer the label "killer robots".

"I urge delegates to take bold action," said Michael Moeller, head of the UN's Conference on Disarmament.

"All too often international law only responds to atrocities and suffering once it has happened. You have the opportunity to take pre-emptive action and ensure that the ultimate decision to end life remains firmly under human control," he said.

That was echoed by the International Committee of the Red Cross, guardian of the Geneva Conventions on warfare.

"The central issue is the potential absence of human control over the critical functions of identifying and attacking targets, including human targets," said Kathleen Lawand, head of the ICRC's arms unit.

"There is a sense of deep discomfort with the idea of allowing machines to make life-and-death decisions on the battlefield with little or no human involvement," she added.

The four-day meeting in Geneva aims to chart the path towards more in-depth talks in November.

"Killer robots would threaten the most fundamental of rights and principles in international law," Steve Goose, arms division director at Human Rights Watch, told reporters.

"The only answer is a pre-emptive ban," he added.

UN-brokered talks have yielded such bans before: blinding laser weapons were forbidden by international law in 1998, before they were ever deployed on the battlefield.

Automated weapons are already deployed around the globe.

The best-known are drones, unmanned aircraft whose human controllers push the trigger from a far-distant base. Controversy rages, especially over the civilian collateral damage caused when the United States strikes alleged Islamist militants.

Perhaps closest to the Terminator-type killing machine portrayed in Arnold Schwarzenegger's action films is a Samsung sentry robot used in South Korea, with the ability to spot unusual activity, talk to intruders and, when authorised by a human controller, shoot them.

Other countries at the cutting edge include Britain, Israel, China, Russia and Taiwan.

But it's the next step, the power to kill without a human handler that rattles opponents the most.

Experts predict that military research could produce such killers within 20 years.

"Lethal autonomous weapons systems are rightly described at the next revolution in military technology, on par with the introduction of gunpowder and nuclear weapons," Pakistan's UN ambassador Zamir Akram told the meeting.

"In the absence of any human intervention, such weapons in fact fundamentally change the nature of war," he said, warning that they could undermine global peace and security.

The goal, diplomats said, is not to ban the technology outright.

"We need to keep in mind that these are dual technologies and could have numerous civilian, peaceful and legitimate uses. This must not be about restricting research in this field," said French ambassador Jean-Hugues Simon-Michel, chairman of the talks.

Robotics research is also being deployed for fire-fighting and bomb disposal, for example.

Campaigner Noel Sharkey, emeritus professor of robotics and artificial intelligence at Britain's University of Sheffield, underlined that autonomy is not the problem in itself.

"I have a robot vacuum cleaner at home, it's fully autonomous and I do not want it stopped. There is just one thing that we don't want, and that's what we call the kill function," he said.

Supporters of robot weapons say they offer life-saving potential in warfare, being able to get closer than troops to assess a threat properly, without letting emotion cloud their decision-making.

But that is precisely what worries their critics.

"If we don't inject a moral and ethical discussion into this, we won't control warfare," said Jody Williams, who won the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize for her campaign for a land-mine ban treaty.

1726734110-0/BeFunky-collage-(10)1726734110-0-208x130.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ