Learning statehood: Importing lessons in tolerance

Academics outline national strategy for combatting extremism.

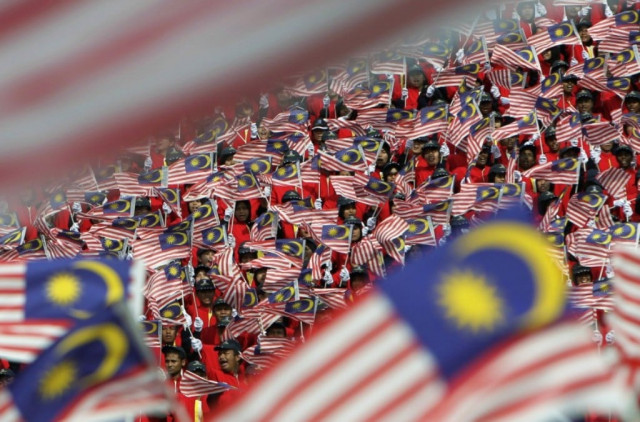

Malaysians celebrate the 48th anniversary of Malaysia Day as well as the 54 years of Independence Day, in Kuala Lumpur. PHOTO: REUTERS

Perhaps it is because of the dire state of religiously-motivated violent conflict in Pakistan, or our collective inaction about the violent crises we face. But Pakistanis often look towards other countries as exemplars for tackling similar problems somewhat successfully.

Islamabad-based think-tank, Centre for Research in Security Studies (CRSS) and the German nonprofit organization, Heinrich Boll Stiftung (HBS) Pakistan on Friday hosted two Malaysian academics to find out more about how Malaysia has been attempting to find a balance between state, religion and democracy.

Centre for Defence and International Security Studies’ Director at the National Defence University Malaysia, Professor Ruhanas Harun and University Utara Malaysia professor Dr Karmarulnizam Abdullah presented the Malaysian perspective at the discussion forum.

Harun said that Malaysians have avoided or managed the potentially violent conflict that may emerge when religion and state engage in a confrontation. Citing the Malaysian experience, she said “co-habitation between religion and politics is possible, provided that each respects the overarching framework of governance as well as one other’s existence”.

Violent conflict could be avoided through “harmonisation”, and the prevailing (socioeconomic) conditions in the country have aided Malaysian authorities in controlling excesses done in the name of religion, said Harun.

However, she said that conditions for harmonization differ from country to country, and so, one country’s example could not be perfectly replicated in another country.

Harun’s words could not be truer because, according to her, Malaysia would like to keep both the identity of being a “secular democracy” and the identity of a “Muslim country.” And yet, there is a deep contradiction in this statement because Malaysia does not allow Shiite Muslims to practice or promote their brand of Islam openly. In October 2013, a Malaysian court also barred non-Muslims from using the word “Allah.”

These actions are arguably against the spirit of secularism and would be difficult to even consider for implementation in a multi-religious, multi-ethnic country such as Pakistan.

The panellists also went over the Malaysian Internal Security Act, which was repealed last year after decades of enforcement. The law was used by Malaysian authorities to tackle potential threats of violent conflict. It allowed the authorities to arrest any person who would be considered a threat to national security and allowed detention without trial for 60 days, according to the Malaysian academics.

The act’s contents sound similar to the Pakistan Protection Ordinance, an anti-terror law which was approved by President Mamnoon Hussain in October 2013, but was later rejected by a standing committee of the national assembly. The ordinance was slammed by human rights groups and civil society representatives for being draconian.

There were, however, some positive messages from the talks given by the two Malaysian academics. According to them, the Malaysian government in the 1980’s used a three-pronged strategy to deal with religious extremism which included accommodation, co-optation and confrontation where necessary. The first two prongs of this strategy allowed for an environment of “tolerance” to take root. However, the way Malaysians define tolerance might be problematic.

Perhaps, what Pakistan needs is its own brand of tolerance, and in good quantity.

Published in The Express Tribune, January 19th, 2014.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ