We need Manto more than ever

Curricula at universities must include his writings and an active effort must be made to salvage his legacy.

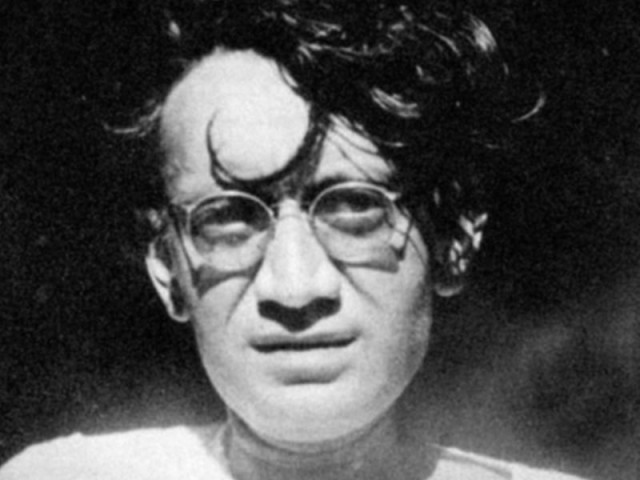

Clearly, a writer who places ‘sinful characters’ on morality pedestals will not be celebrated by a state which has propagated values of an exact opposite nature to preserve its statehood. PHOTO: FILE

It is true that Manto’s fiction puts out some very unorthodox ideas, but the claim that such ideas aim to damage moral sensibilities is questionable. Manto made no secret of being averse to didactic fiction. His training as a journalist meant that he had a penchant to tell it like it was, with no intention of preaching. Hence, arguing that the writer sought to advocate anything is problematic. Countless critics have argued that the unorthodox content in Manto’s works did not serve to weaken moral fibres as most of it was strictly matter-of-factly and devoid of the ponderous metaphors which were characteristic of Urdu fiction produced during the time: it was all simply a mirror of reality. The need of the time is to embrace the legend that Manto was. Curricula at universities must include his writings and an active effort must be made to salvage his legacy.

Published in The Express Tribune, January 19th, 2014.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ