The Reluctant Fundamentalist

The Reluctant fundamentalist re-informs global debate on relationship of Pakistanis-Americans in post-9/11 world.

Mira Nair’s latest work based on Mohsin Hamid’s book re-informs the global debate on the relationship of Pakistanis and Americans in a

post-9/11 world. PHOTO: ISHAAN NAIR & QUANTRELL COLBERT

More than a decade since that day Pakistanis still find themselves on the defensive. In many cases, the makers of our art, literature, music and film too have to first extricate themselves or rise above the tiresome dichotomies spawned by 9/11. And even as our artists break free from these restraints, their work is still often helplessly informed by them — by sheer virtue of trying to overcome them.

Take this example: Mira Nair, the director of The Reluctant Fundamentalist that has just opened in cinemas, recalls the effort that went into turning Mohsin Hamid’s 2007 book into a film script. One potential scriptwriter had advised: “First off, we’re going to have to drop the title. You couldn’t drag me to see a film with the word ‘fundamentalist’ in it”. Deciding to keep the title became a question and its answer turned into an act of rebellion and submission at the same time.

Whether you liked Mohsin Hamid’s book or not, we would still highly recommend watching Mira Nair’s interpretation of it. For she takes us back to the Question of what 9/11 has done to us. No matter which side you were or are on, whether you cared or not subsequently and especially if you are fed up of it all.

The plot

At its heart, The Reluctant Fundamentalist is a thriller but one that is less about well-choreographed fights. It is propelled by the classic conflict-crisis-resolution formula embedded in one man’s experience as he is thrust into a world where you were either with them or against them.

PHOTO: ISHAAN NAIR & QUANTRELL COLBERT

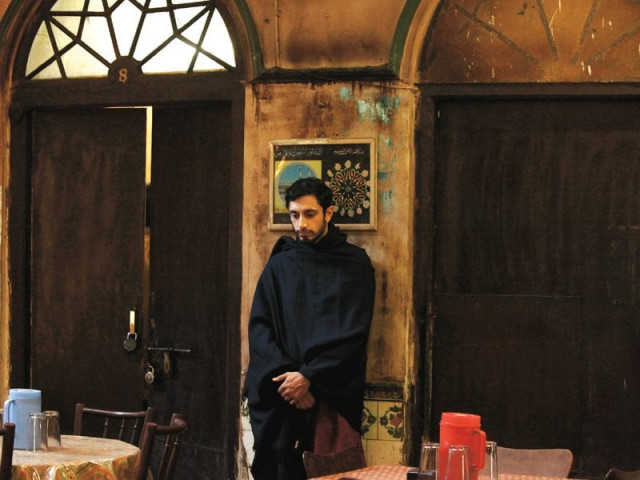

That character is Changez, who we first meet as a young professor in Lahore, played by the impossibly beautiful Riz Ahmed.

When the film opens Changez is being interviewed by a thickset American journalist by the name of Bobby Lincoln (Liev Shreiber) in ‘Lahore’ (recreated in Old Delhi). Bobby believes that Changez was involved with the terrorists who recently kidnapped his friend, an American academic at the university.

The American journalist’s perceptions of Changez are used to cleverly strip stereotypes: young fiery-eyed Islamist intellectual with a beard who rejected living in America after studying there (He must be a terrorist or at least a sympathizer). But as Changez keeps warning Bobby and us: Looks can be deceiving. I am a lover of America.

Mira Nair doesn’t stop there, though. She drives her point home repeatedly by making even us doubt Changez, right till the end. And then we are ashamed we ever did. This is one of the film and book’s strongest lessons: the stereotypes are hard to shake off, especially the ones we have about ourselves.

Changez agrees to talk but only if Bobby is willing to listen to his life story. This was another clever message — first you have to listen, to the whole story. Indeed, is this inability for the two sides to listen to each other not part of the problem? And is art’s job not to remind us?

We are pulled in to Changez’s transformation from an ivy-league school graduate to what he is today. We can all guess what made him go home after 9/11 even though he was working as a financial analyst and had a beautiful girlfriend who is a photographer (played by Kate Hudson who didn’t quite look right for the role). The strip searches, the police harassment, the widening schism caused by interpretations of the act of terrorism did not help. That is not what will interest you. It is how Changez reasons through the crisis that will surprise you.

Isn’t it an irony that the word ‘changez’ in French means change?

The great debate

Other filmmakers have taken on the vexing faultlines created by international terrorism. Karan Johar’s My Name is Khan aimed to re-analyse the identity of Muslims but its patina of Johar’s signature superficiality killed it. Pakistan was not at the centre of this story anyway.

Then there was Shoaib Mansoor’s Khuda Kay Liye, a film that played a seminal role in the rebirth of Pakistani cinema. It also tried to deconstruct the post-9/11 Pakistani identity as well. In a way, The Reluctant Fundamentalist is Khuda Kay Liye done right with a bigger budget and by a much more experienced director.

In the end, Mansoor failed to take a side. (This did not necessarily dent its popularity). Khuda Kay Liye was unsure of its own central message and failed to persuade that it had really understood the issues it was trying to tackle. For many it thus emerged as an apologist film. The audience feels some form of catharsis but the debate is not driven forward. We do not learn anything new.

This is where Mohsin Hamid and Mira Nair are right on the money. They lay out the unfair treatment meted out to many Pakistanis after Sept 11 but do not pander to their bruised egos. This would have reduced them to ‘victims’ and the film would have become a victim to the very black and white thinking it wants to move away from. (It failed on one front though, by demonizing the Americans towards the end)

There is a fine tightrope to tackling ‘victimhood’. The writers come really close to making us feel sorry for Changez when he says to Bobby: “You picked a side after 9/11. I didn’t have to. It was picked for me.” It is only Riz Ahmed’s non-whiny tone that allows this line to skim past by the skin of its teeth.

Riz Ahmed does a brilliantly restrained job of revealing his anger and frustration inch by inch as Changez’s life starts to unravel in New York. When his girlfriend Erica picks him up from the airport after he has been strip-searched, she incredulously asks how, just how could something like the terrorist attack have happened? Changez’s answer is curt but quiet and comes after the slightest of pauses: Why do you think I would know?

This kind of writing is the strength of this film.

When Erica and Changez are courting, their couple’s inner joke is: I had a Pakistani. But when Erica uses this line as part of her photography exhibition its double entendre ruins it because of a wider context in the post-Sept 11 New York. Was she reckless to use her shared private life with Changez to make a political point or was it simply a case of just another American not quite understanding just exactly what 9/11 was?

The performance

It took Mira Nair over a year to find the right man to play Changez, a Pakistani who spoke colloquial Urdu but dreamt in English and who was just as much at home at a Wall Street bash as a Lahori dhaba. British actor and rapper Riz Ahmed may have been a risky choice but he delivers through and through.

PHOTO: ISHAAN NAIR & QUANTRELL COLBERT

This is why the film is flooded with close shots of his face, treating us to a dizzying spectrum of nuanced emotional states. The secret lies in his wide eyes and their black pupils that dilate and narrow at the right times. Yes, he has been given five different looks and three beards, but the cosmetics would not have been able to carry a hysterical performance.

We encounter him as an eager young Princeton graduate, open-faced and full-lipped, almost Grecian in profile, a young prince in a world for the taking. He transitions from this, without the slightest of facial muscle flickers, to darken his expression when his life in America starts to fall apart. His weeping is real. His confusion expertly blank. How many actors can give an honest interpretation of helplessness while being cavity searched at the airport while holding their groin?

And then, he appears ever so slightly gaunt, even wizened towards the end after he has made his choices. His moustache makes his upper lip thinner, his look sharper. There is just a smudge of fatigue under his eyes. His stiff slick Brylcreened capitalist helmet has gone. Do we detect a hint of Zaid Hamid? We are not sure. The side parting in his hair makes him look innocent but we can’t trust the look.

PHOTO: ISHAAN NAIR & QUANTRELL COLBERT

Management of Changez’s physical transformations were carefully orchestrated with the choice of the film’s look. Mira Nair explains that she wanted to have a “palpable air of unease in every scene — a sense that anything can happen at any moment”. This is why the camera was never fixed on a tripod or static. It was always moving in the hands of cinematographer Declan Quinn or suspended on a bungee cord. It was a technique that worked without turning irritating or veering too much to the look and feel of a documentary film.

Happily, the filmmaker did not fetishize locations like ‘Lahore’ or Istanbul. There were no attempts to capture the ‘heat and dust’ of the city through some hackneyed Orientalist lens. Setting supported the story but mercifully did not overwhelm it.

PHOTO: ISHAAN NAIR & QUANTRELL COLBERT

A few strains of confusion creep in over Changez’s firebrand university speeches and the jihadi recruitment on campus. It was similarly a little unclear what the motivation for the riot was. For anyone familiar with the workings of groups like Hizbut Tahrir or Pakistan’s daily protests, it was easy to suspend disbelief but for foreign audiences perhaps these scenes could have been fleshed out a little more.

The music

Well, of course Mira Nair would have chosen Kangna, safely one of the most iconic pieces of music of these times. Critics will call it an orthodox choice, putting a qawwali at the opening of a film on Pakistan. But watch closely. As Fareed Ayaz and Abu Muhammad sing it, we simultaneous cut to the scene where the American academic is being kidnapped elsewhere in Lahore. Mira Nair has said that she wanted Fareed Ayaz’s crimson paan-filled mouth to echo the blood of the kidnapping but don’t be distracted by that symbolism. Something much more clever happens.

PHOTO: ISHAAN NAIR & QUANTRELL COLBERT

As the kidnappers ambush the American academic and his wife on the street, the violent pitch of the refrain from Kangna rises to a near scream. “Kangna de de!” Give back the bracelet! The wife is beaten and thrown onto the street as the terrorists drive off with her husband. She runs behind the car screaming for help. “Tori binti karoon,” sing the qawwals. I beg and beseech you.

We are treated to another masterful use of a Pakistani song towards the middle of the film with Atif Aslam’s rendition of Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s Mori Araj Suno made legend by Tina Sani. It is placed at the point when Changez finds himself in Istanbul, ready to take the wrecking ball to a Turkish publisher’s company. We see him silhouetted against the Blue Mosque as Aslam’s quavering high notes tug at our heartstrings. Changez is at a crossroads, as Istanbul is between two worlds. He is shown sitting in the Blue Mosque but he doesn’t pray just yet in another example of sophisticated exercise of restraint in the film.

The film has been well received abroad and it should be dubbed for the wider audiences in Pakistan. Sadly, certain key pieces of dialogue are unfortunately blanked out and one or two sexy scenes have been cut.

Mira Nair could only understand so much of Pakistan as a relative outsider. But that does not necessarily matter because the film gets all the right pieces right. Indeed, perhaps Nair is unaware of the effect it can have. Take for example the magnitude of what she was saying in interviews to publicise the film: You never know what is going to happen next.

This, as any Pakistani will tell you, is how we live each day in this country.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, June 2nd, 2013.

Like Express Tribune Magazine on Facebook to stay informed and join the conversation.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ