However, contrary to popular expectation, Pakistan has received over a billion dollars (about 85 billion rupees) in relief goods, grants and soft loans from the international community, according to the latest data available from the Economic Affairs Division of the Ministry of Finance.

Where is it coming from?

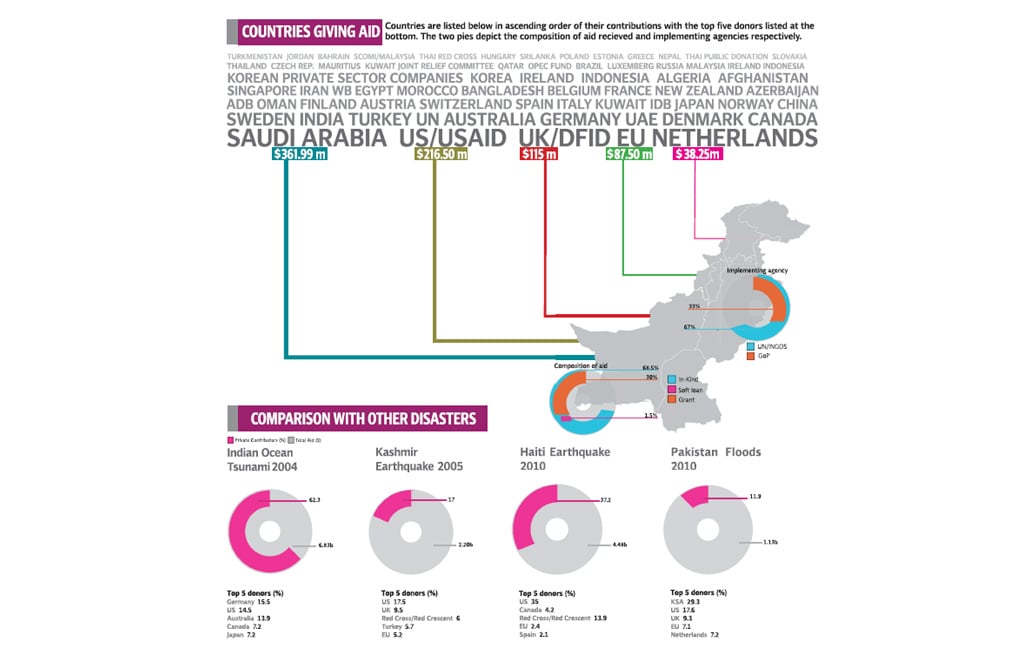

At present, 61 countries and six multilateral institutions have committed from $50,000 (Hungary) to over $250 million (Saudi Arabia) for flood relief. The majority of this aid, almost 62 per cent, comes from the top five donors (read: all-weather friends) Saudi Arabia, the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union and the Netherlands.

The top 20 donors combined have contributed about 94 per cent of the total amount pledged.

While the largest donation by a government comes from the United States ($216 million), Saudi Arabia has contributed a whopping $362 million through a combination of public and private contributions, including a Saudi Public Assistance campaign through which $242 million were collected.

What kind of aid?

Of course, donor countries do not send in wads of cash in sacks, and for good reason. As the disaster unfolded, immediate relief was high on the agenda and consequently, ‘in-kind’ relief comprises roughly 70 per cent of the aid committed. So far, one-third of this aid has already arrived, including food, water, clothing, shelter kits, tents and medicines.

A little less than 30 per cent of the aid comes in the form of grants, primarily monetary aid, committed for specific projects. The nature of these grants varies across donors.

While some countries, like Malaysia, have deposited it directly in the Prime Ministers’ Fund for Flood Victims, others are channelling it through various United Nations (UN) organs and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs). About one-sixth of the committed grants have been disbursed so far.

The remaining portion of aid, approximately 1.5 per cent, comes in the form of soft-loans, loans with low interest rates and longer pay-back periods.

However, once the relief phase is over and the country moves to rehabilitation and reconstruction, soft loans will be the primary form of aid Pakistan will receive from donor countries and multilateral institutions.

Where is it going?

Trust deficit, arising from concerns regarding the government’s ability to appropriate funds judiciously, was a major cause of the reluctance to donate. The numbers reflect this fact: two-thirds of the aid committed has been, and is being, delivered through UN bodies like the World Food Program, and international organisations such as the Red Cross and Red Crescent. Only one-third of it is being delivered through the Pakistani government.

Interestingly, Saudi Arabia and China are the only two donors amongst the top 20 who have channelled their entire aid through the government. With the exception of Turkey, Japan and Kuwait, each of whom have given less than half of their committed aid to the government, all the major donors preferred to send in their grants and goods through other channels.

One billion too little?

Pakistanis complain that the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and the 2010 Haiti earthquake appear to have evoked a more generous response from the international community. Around $6.8 billion were raised for the tsunami and Haiti was able to collect approximately $4.5 billion in pledges – much more than Pakistan’s one billion dollars. Even the 2005 Kashmir earthquake raked in twice as much in initial pledges. Why the penny-pinching now?

Global financial conditions aside, a closer analysis of the aid committed to previous disasters reveals another story: 62 per cent of the Tsunami’s and one-third of Haiti’s pledges came from private individuals and organisations, compared with a mere 12 per cent in the case of present floods. While we seem to have moved foreign governments, we have apparently not been able to stir up the philanthropy of foreign individuals, who tend to be more generous than their governments.

The Saudi public is an exception that highlights this point: citizens donated more than twice as much as their government and by far comprise the largest donor group in present crisis. While residents of various countries have organised fund-raising campaigns, the lack of a streamlined aid-collection mechanism in Pakistan means accounting for these donations would be difficult.

Will it all arrive?

Aid is tricky business. At the best of times, financially speaking, there is a deficit between the funds pledged and the amount received. Now is certainly not the best of times. How much of these billion dollars should we be realistically expecting to trickle in?

“Most,” believes Raza Rumi, a development sector consultant who has worked during the Kashmir earthquake relief and rehabilitation process. “About half of the relief pledges have been received, so this should not be a matter of concern,” muses Rumi before warning that the real challenge lies in the reconstruction process.

What next?

The reconstruction price tag on the Kashmir earthquake in 2005 was estimated at $6 billion. Of the total, $4.8 billion of this came from foreign governments and the remaining $1.2 billion was pitched in by the government of Pakistan, according to an official at the Earthquake Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Authority (ERRA). Five years later, 85 per cent of the foreign commitments and 60 per cent of the governments’ funds have been utilised, disclosed the official.

If one pays heed to these numbers, there is little reason to be pessimistic. But things are drastically different now. The global economy is barely limping its way out of a catastrophic recession and Pakistan is internally in shambles. Add to this 20 million victims and between $15 and $20 billion required for reconstruction and you have a nightmare.

Rumi’s warning makes sense. Most, if not all, of the amount required for reconstruction will come in the form of low-interest, long-term loans. At present, about $3.5 billion have been committed by the International Monetary Fund, World Bank and Asian Development Bank at favourable conditions. Kerry-Lugar’s annual $1.5 billion over the next four years will also help. But besides that, little else seems to be on the horizon. The government is mulling surcharges and flood taxes but both are politically explosive propositions, especially given the lack of credibility of a fiscally irresponsible regime.

Whether the floods are harnessed as an opportunity to clean its own house (read: slash non-development expenditure) and jump-start a massive reconstruction programme by the fledgling democratic government is both a question and wishful thinking at this point.

Published in The Express Tribune, September 15th, 2010.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ