Goonda raj

The real-life characters behing the goonda and gandasa era of Lollywood.

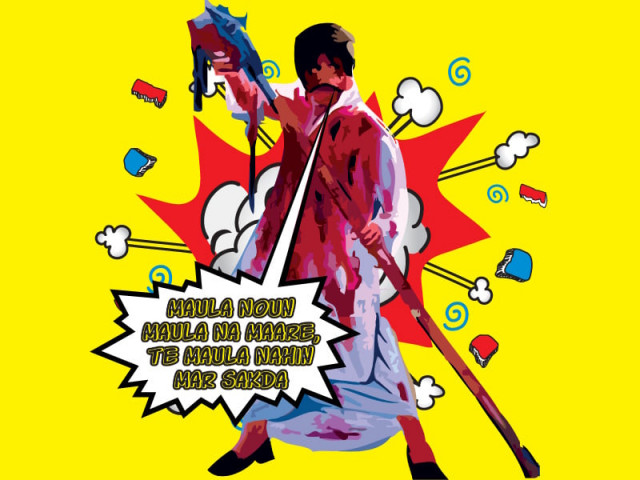

The scene is from the 1979 Lollywood film Wehshi Gujjar. On the face of it, to any modern critic of the Punjabi film industry, the story follows the ‘tried-and-tested’ Punjabi film formula: honour, bharaks (grandiose boasting), machismo and violence.

But there is something unique about this film. Not that Wehshi Gujjar is the second super-hit, after the success of Maula Jutt (1979), in the late 1970s to 80s period of Punjabi cinema, but the film is the first to be inspired by the story of a real-life goonda.

Jagga Gujjar, the film’s lead character, is a portrayal of Jagga Gujjar of Chowburgi, who is remembered till today for imposing the notorious ‘Jagga Tax’ on Lahore’s Bakra Mandi in the late 1960s.

“The film was actually going to be named Jagga Tax but the censor board did not pass the name. It was renamed Wehshi Gujjar to get it approved,” says Jagga’s nephew Chaudhry Imtiaz Gujjar.

Imtiaz, who is better known as Tajja, lives at the Dera Buddha Gujjar in Samnabad. This is the same dera which is referenced in the films Wehshi Gujjar, Puttar Jaggay Da (1990) and Jagga Tax (2002). We enter through an arched gateway and walk past a parked land cruiser. Tajja is seated on a wicker lawn chair, with a loaded assault rifle lying next to him. “We are people with a lot of rivals and enemies,” explains Tajja, gesturing offhandedly at the gun.

The most famous of these rivalries, with Qila Gujjar Singh’s Shukerwala family, has since turned into a friendship but clearly that’s no reason for Tajja to let his guard down. Inheriting his uncle’s mantle, Tajja now runs Jagga Gujjar Productions. “The first film I produced was Puttar Jaggay Da in 1990, which was a success. Then I made Jagga Punjab Da, which I had to release as Gujjar Punjab Da (1994). A decade later, I released Jagga Tax.”

Tajja is clearly proud of his prolific film-making. “If you check the Guinness Books of World Records, you will find that I hold the record for the shortest time taken to produce a movie: 36 days to produce Jagga Tax, including the script, music and production at Bari and Evernew Studios. Then I made Numberdani (2010) in 30 days. Gujjar Punjab Da also took 30 days.”

Wehshi Gujjar, the first film on Jagga Gujjar, was made by Jagga’s brother, Chaudhry Miraj Din. “The story is more fiction than fact… but it is definitely about our family,” he says.

“While it is true that Gujjars do not sell milk on the 11th, no such event [with the shopkeepers] actually happened,” he says of the film’s opening sequence. “Puttar Jaggay Da is closer to the truth but it is also not a true story either.”

So what is the true story?

“Jagga was the name given to my uncle by his mother. From a very early age, he wanted to be remembered,” Tajja tells us. “People forget one thing… Jagga Gujjar spent only six months outside of jail before he was killed.”

Jagga, he explains, was jailed at the age of 14 for avenging the murder of his brother, Makhan Gujjar, at a mela in the year 1954. “Jagga killed the man who shot his brother eight days later. Holding Acha Shukerwala responsible for Makhan’s murder, Jagga organised an attack on Shukerwala from his jail cell. Two of Shukerwala’s men died while Shukerwala was wounded in the attack,” says Tajja. “He also killed a man from Acha’s group in jail before he was released on early parole in 1968 at the age of 28.”

“The fame Jagga earned was in the six months he was able to live out of jail,” he says. “I don’t know what story to tell of him. Wherever he went he fought people. He went to jail in an early age but continued to fight antisocial elements in society.”

The film Puttar Jaggay Da’s opening sequence is set in a Chowburgi market. When Buddha Gujjar, Jagga’s father, stops his horse carriage at a shop, people gather around him and sing praises of Jagga Gujjar to him. “Your son Jagga stopped a man from eve-teasing my sister,” says one. “Your son, Jagga, stopped a bootlegger from selling liquor,” says another. “Your son, Jagga, ensured that my husband returns home on time,” says a woman.

“This is true… the people in this neighborhood feared Jagga because he stopped young boys from eve-teasing and stopped others from bootlegging or selling narcotics,” says Tajja.

What is forgotten by most Punjabi film critics is that the goonda did not suddenly enter Punjabi film in the 80s. It was in fact in the 60s that the first real-life ‘goonda’ entered the film industry as a producer, and this is also when the real social context for these characters and stories was established: the enforcement of the Goonda Act in 1968.

The enforcement of the Goonda Act is one of the many events conveniently forgotten by many historians of Punjab… but film producers of the 80s did not forget it. Instead they re-wrote the script of the Goonda Act period through film and thereby reclaimed the role of the goonda in popular imagination.

It was, in fact, Jagga’s great rival Acha Shukerwala, the pehlwaan from Qila Gujjar Singh, who was the first goonda to step into film production in 1965 with the hit film Malangi (1965). But contrary to what you may think, he was far from a social outcast and a criminal as far as the state machinery was concerned.

“Shukerwala was West Pakistan Governor Amir Muhammad Khan Awan’s right-hand man,” explains Kamran Chaudhry, producer of Bhai Log (2010). Chaudhry is Shukerwala’s nephew and is continuing the family’s legacy of film production. His office is located in Lahore’s film district, the Royal Park, opposite the Buddha Gujjar building, which is still owned by Jagga Gujjar’s family.

“Shukerwala would act as an enforcer for Amir Muhammad Khan… if there was a public agitation against a price hike, Shukerwala would be called to enforce ‘law-and-order’… If a politician was raising his voice, Shukerwala would be asked to deliver a ‘warning’,” Chaudhry says.

Amir Muhammad Khan, also the Nawab of Kalabagh, was in turn known as the right-hand man of then President Field Martial Ayub Khan. According to film lore, Governor Khan once ordered his men to abduct film heroine Neelo and forced her to dance for the Shah of Iran despite her refusal. Habib Jalib is said to have visited her in hospital after she attempted suicide following the humiliation at the hands of Khan. He composed the verses:

Tu ke na’wakif-e-aadaab-e-ghulami hai abhi

Raks zanjeer pehn ker bhi kiya jata hai

(You are still unaware of the etiquette of being a slave

One dances even when chained…)

The verses were later sung by Mehdi Hassan in the film Zarka (1969) and became the metaphor to remember the late governor with.

“The Goonda Act was enacted due to an incident involving my family,” Karman Chaudhry relates. “Acha Shukerwala had a rivalry with another group, which led to someone getting killed. During the hearing in the sessions court, one of the case witnesses was shot dead and his family took the body outside Governor House to protest. The then Governor Musa Khan imposed the Goonda Act [1959]. Acha and members of our family were rounded up and put in jail as suspects in the sessions court shootout case, and other known goondas were shot dead in staged police encounters.”

Tajja says Jagga Gujjar was the first person arrested after the enforcement of the act. “He was killed in confinement and then his body was thrown in the Bakra Mandi,” he says. “We were middlemen in the Bakra Mandi and the butchers tried to frame our family after Jagga was murdered. They murdered two of my brothers claiming they had returned to take Jagga Tax, but Jagga had never taken any tax himself. Police just created the propaganda of Jagga Tax to justify killing him… he barely spent six months out of jail before he was killed.” Tajja also says that there were between five and seven murder cases against Jagga. “Our entire family was forced to live within the confines of the Raiwind police area during this time.”

While the Goonda Act remained in force, over a dozen men labelled as goondas, including Jagga Gujjar and Kaka Lohar, were killed in police encounters across the Punjab area (then a part of the One Unit).

Coming out of this period, the families who had lost their relatives to the Goonda Act began pouring their money into film to reclaim their memory by offering a counter-narrative to the state.

The trend started when Chaudhry Miraj Din produced Wehshi Gujjar, and continued till Shahia Pehlwan of the Walled City stepped into film production. Riaz Gujjar, also considered a goonda, stepped into film production as well.

This era of Punjabi film featured not only a new generation of producers, but also saw the rise of new directors and actors. Filmasia distributor Mian Tariq, explains that this period was marked by the rise of actor Sultan Rahi. “Maula Jutt was released in 1979…and the rest is history,” he says.

“One of the lesser known stories is that a film, Wehshi Jutt, had been produced before Maula Jutt. Both films had taken Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi’s short story Gandasa on the culture of Gujranwala as the inspiration for their script.”

That one of the quintessential Urdu intellectuals was instrumental in the genesis of a genre of film considered so antithetical to the Pakistani cultural project is one of the great ironies lost in the cultural debate around the Punjabi film genre.

While Qasmi’s Gandasa might have unwillingly served as inspiration for the genre, Tariq considers the secession of East Pakistan in 1971 as another critical factor for the rise of the Punjabi film.

“Before East Pakistan seceded, Urdu film distributors had three circuits to distribute their films to: Punjab and the NWFP, Sindh and Balochistan, and East Pakistan. From the 1970s, we were left with only two film circuits and half the audience,” Tariq says.

“The death blow for veteran producers was General Ziaul Haq’s dictatorship… 344 films were banned for ‘violating Islamic norms,’” he says.

Even Maula Jatt was not given clearance by the Censor Board but managed to attract huge audiences to cinema houses, thanks to the Lahore High Court’s stay order on the ban, which remained in effect for two years. Then Jagga Tax cleared the censor after being renamed Wehshi Gujjar, and so a new chapter in the history of Pakistan film was opened: the goondas, who were successively nurtured and disposed off under Ayub’s rule reentered the public imagination under another dictator, General Ziaul Haq. Ironically, all this happened as the State pretended to be building a more puritanical culture.

The increasing popularity of Punjabi films in this period, while wriggling past an otherwise strict censor board, was not received kindly from all quarters. “There was an innate rivalry between Urdu and Punjabi filmmakers… most Urdu directors did not consider Sultan Rahi a hero,” Tariq explains. “To them, a hero was like a diamond… a beautiful individual who, when on screen, boys and girls would fall in love with.”

As old directors began to distance themselves from the new Punjabi circuit, a new set of directors replaced them. “The culture of film and the culture of the film studio completely changed with the entry of Punjabi film and the goonda as a producer,” Tariq says. “The films released in the 1980s were based on the goondas of the 1960s; the films released in the 2000s were based on the goondas of the 1990s. This is the untold story of Punjabi film.”

Seated at Evernew Studios, Shahid Rana, who considers himself a bit of an outcast amongst directors, says, “Society is what makes a goonda. When I made the film Goonda (1993), this was the concept of it. Sultan Rahi’s character is forced to confront a powerful man who attempts to rape a woman on a street crossing. When the man points a Kalashnikov at him, Rahi ends up shooting him by mistake and is sent to jail. After he returns from jail, it is people that make him a goonda to fulfill their own ends… Rahi is, if anything, the ‘reluctant goonda’… he becomes what he does because it is society that needs him to be that way.” Rana says.

Rana’s current project is to make the film Jajji Bahadur, based on the life of Shahia Pehlwan’s rebel son, Jajji (real name: Javed Ilyas Butt). He is directing the film for Shah Din Productions, also known as Shahia Productions, for whom he has directed a number of films earlier, including Kalka (1990), Goonda and Puttar Shahiay Da (1986). “Jajji was killed due to their family enmities in the mid-1970s. He was famed for his bravery and had fought off numerous police encounters and survived,” he says.

Jajji’s brother Shahabuddin Butt also entered film production with the film Genterman in 1969. The mantle was then taken up by their two younger brothers, Pervaiz Butt and Babar Butt, who produced Rana’s Kalka and now Jajji Bahadur.

“Having made Puttary Shahiay Da for the family earlier, the brothers now want me to make a film with Jajji’s name in the title,” Rana says.

The film’s title poster, which hangs on a wall in Shahia Pehlwan’s dera near the Taxali Gate features the real-life photograph of Jajji. A number of pictures of Shahia Pehlwan with President Ayub Khan are also on display. Some of Shahia’s nephews have also acted in the films their uncles produced.

“The film will depict Jajji’s true story. He was a wrestler who was forced onto the wrong side of the law. The police opposed him for his bravery and his parents tried to make him reconsider his path, but he became too set in his ways and was killed,” Rana says.

Caste identities in Punjab have continued to find themselves in a tense relationship with the Pakistani state and its cultural project. This tension has found its expression through finding for itself an anti-hero, the goonda, and representing his tragedy as an attempt to negotiate a space within the cultural realm.

Punjabi film has undergone a transformation from Malangi in the 60s to Wehshi Gujjar in the late 70s all the way to Jajji Bahadur in the 2010s. Over the last two decades, Punjabi films have been unable to replicate the financial success of previous goonda-oriented scripts.

The families of former goondas who entered film production have also not been blind to the need for new stories to reflect changing audiences. The hit films Chooriyan (1998) produced by the Jagga Gujjar family, Kalka from Shah Din Productions, and Bhai Log (2010) from Chaudhry Kamran represent attempts at carving out a new niche for Punjabi film.

Khurram Bari, the chief executive of Bari Studios, speaks of an abandoned attempt by an educated Gujjar family to produce a film titled Gentleman Gujjar. This, coupled with admissions by directors, producers and studio owners that the formula Punjabi film is no longer profitable, points towards a need for Punjabi film to reassess the changing place of caste identities within contemporary Punjab.

“When Jagga Gujjar was released from jail, a crowd of people is said to have stood outside to greet him at Mazang Chowk. When he died, thousands joined his funeral,” Tajja recollects. More recently, the funeral of local goonda Tipu Truckanwala also saw a massive crowd in attendance.

If this is true, then the popularity of films about goondas should come as no surprise to anyone. Nor should one forget that almost all of those killed when the Goonda Act was enacted in 1968, and those killed in police encounters in Shahbaz Sharif’s second term as chief minister of Punjab in the late 1990s, have at least one film to their names.

The goonda, considered the anti-thesis of the law, has, if nothing else, carved out an indelible chapter for himself in the history of Pakistani cinema. That alone is enough to give the goonda, and the late Sultan Rahi, immortality.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, November 25th, 2012.

Like Express Tribune Magazine on Facebook and follow at @ETribuneMag

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ