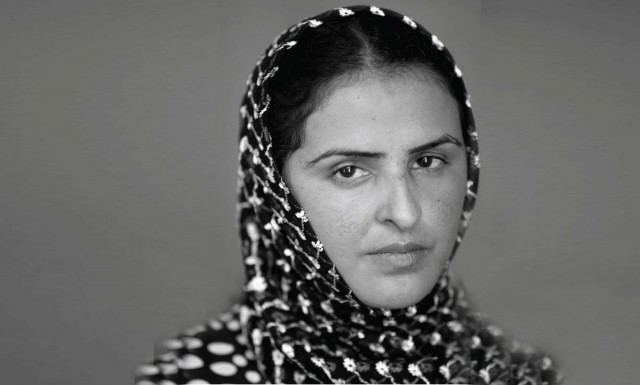

Against all odds

All these years later, and Mukhtaran Mai (also known as Mukhtar) is still fighting her case.

Despite the support she eventually gained as a cause célèbre, victim of one of Pakistan’s more infamous crimes against women, in spite of the help provided to Mukhtaran nationally and internationally, her trials are far from over, and amazingly, all these years later, the politicians of Muzzaffargarh are still pressuring her to withdraw her case or face dire consequences. But Mukhtaran, as the world has seen, is not a woman easily bowed.

“I want to remain a symbol for oppressed women until someone shoots me,” she says, without a second thought.

This is a very real possibility, as her persecution and by extension the persecution of her family continues unabated. She claims that Federal Minister for Defence and Production, Sardar Abdul Qayyum Jatoi and MNA Jamshed Dasti continuously threaten her father Ghulam Fareed for a compromise with the Mastoi clan, fourteen members of which are in jail facing life-imprisonment.

“The culprits should remain in jail forever,” she says. “I will never take any decision to withdraw my case from the Supreme Court of Pakistan.”

The feudal bigwigs of the Jatoi, Mastoi and Dasti clans have tried varying means of intimidation, including threatening the seven policemen deployed around her house in Meerwala. “Now they are reluctant to stand guard outside my home and at the girls’ school,” she said.

Mukhtaran’s strongest condemnation though is still reserved for a system which is rotten to the core, the politics of rape in Pakistan which often turn the victim into the criminal — this is the loophole her rivals in Jatoi Tehsil are exploiting to harass her. But she is determined to fight not only for herself but for countless other women through the Mukhtar Mai Women’s Welfare Organisation, which she claims is the only source of relief for the women of southern Punjab. “Donors from Canada and Norway are sponsoring million of rupees annually to run it,” she says.

The Mukhtar Mai Girls Model School, opened with assistance from the Mukhtar Mai Foundation eight years ago, is the first of its kind in Punjab since it offers education to those girls who wouldn’t otherwise have this opportunity. At least three million rupees are spent in educating 650 girls, who would ordinarily face a dismal future. More than 50 employees work for her organisation to run small projects in far flung areas of Punjab and there are 12 women in her Women’s Resource Centre and Shelter Home, all of whom have been thrown out of their homes and disowned by their families in the name of that old chestnut, honour.

Mukhtaran’s drive to bring about change is not merely the result of her well-documented ordeal. She is only too familiar with injustice and deprivation, hailing from Pakistan’s powerless. Her father is a woodcutter and her brothers have blue collar jobs in Mirwala.

Mukhtaran staunchly denies rumours that her personal financial status is that of a billionaire as a result of the financial assistance of foreign donors. “I had money in the billions but I spent it on a school for girls and other organisations assisting women,” she said.

Mukhtaran and her three adopted daughters subsist on the Rs 17,000 monthly stipend of her second husband Nasir Gabol, a policeman, spending on welfare projects the donations that have been made for her cause and in her name, though she has purchased a small flat in the Sabzazar district of Lahore.

On the subject of the law to protect women from harassment, she said that while laws may technically be in place, a paradigm shift is required to implement them. “Women legislators should be more realistic and they must do something for the implementation of the laws which assure the safety of women,” Mukhtaran says.

Her efforts to change the system whereby women are other people’s pawns, sold into virtual slavery, or presented as peace-offerings to settled disputes, are to be awarded with an honourary doctorate from Laurentian University of Canada.

Talking about her lawyer, the celebrated campaigner and barrister Aitzaz Ahsan, she says that he never charged a penny for any of the work he did on her case in the apex court. “He is a man of principle and an iconic character in the judiciary,” Mukhtaran says, adding that his wife Bushra always went out of her way to encourage and help her.

Mukhtaran laments that religious conservatives wield a great deal of power which they use to effectively objectify women and put them in a position whereby they cannot raise their voice against injustice in rural areas, where this conservative view is the dominant one. But there is hope, as evidenced by the national and international media. “The media always stood firm behind me for the rights of women,” she says. “It is the political elite who support the guilty and ignore innocent, powerless women who need justice from them.”

“The local politicians termed my tragedy the Jatoi’s ‘dirty linen’ saying that it shouldn’t be washed in the glare of local attention. If my tragedy is ‘dirty linen’ then their (Politicians) act of gang rape is a ‘turban of honour for waderas’,” she says.

She plans to open welfare centres for women in Kot Addu, Rajan Pur, Dera Ghazi Khan and Layyah. “My family has no land to cultivate and we always worked in landlords’ fields for a living. This was why I could not go to school. But now I can make a

difference.”

Published in The Express Tribune, July 24th, 2010.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ