'PTV' once led Pakistan’s drama industry. What changed?

Veterans of the industry debate whether the state broadcaster is struggling with decline — or resisting change

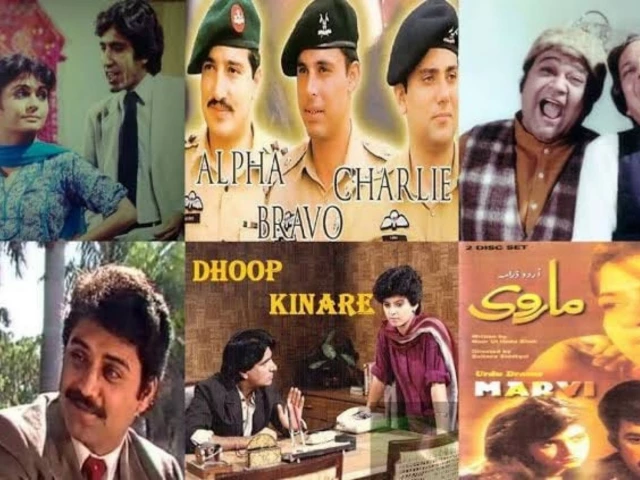

For decades, Pakistan Television shaped what prime-time drama looked like in this country. Its studios produced stories rooted in social anxieties, moral dilemmas, and everyday lives, from the socially conscious serials of the 1970s to the classics of the 1980s and 1990s that still circulate on YouTube and in collective memory. Today, however, as private channels dominate ratings and digital platforms measure success in billions of views, a familiar question has resurfaced: what went wrong with PTV, and can it find its way back?

For many industry veterans, the problem is not a lack of resources but a lack of direction. Actor Javed Sheikh, speaking to The Express Tribune, rejected the idea that PTV has fallen behind because it cannot compete technically. “PTV has everything,” he said. “You have equipment, you have sources. Rawalpindi, Karachi, Quetta, Peshawar, every centre has infrastructure. Like they used to make dramas before, they can do it again.”

According to Sheikh, what’s missing is leadership and intent. “A cultural minister should come, a new MD should come, a chairman should come, someone who changes the whole scenario,” he said. “It’s very simple.” He also pushed back against the argument that the industry has run out of strong writers. “The dramas being watched today on private channels and digital platforms are getting billions of views,” he pointed out. “So where are the writers coming from?”

In his view, audience acceptance is already being proven elsewhere. Pointing to recent projects such as Jama Taqseem, Paamal, Case No. 9, and work by director Nadeem Baig, Sheikh argued that compelling stories still resonate. “If society didn’t accept these stories, they would flop,” he said. “But they’re popular. That’s the rating.”

At the same time, Sheikh acknowledged that creative ambition cannot be separated from financial reality. “Today’s dramas are made in five or ten crores,” he said. “PTV has to raise its budget. Big actors and writers won’t come if they aren’t paid.” Even so, he maintained that the state broadcaster still holds an advantage few others do. “The resources PTV has, no private channel has them.”

Actor Behroze Sabzwari offered a more sombre assessment, describing PTV as an institution slowed down by its own systems. “PTV has been made to sit at home like an old man,” he said. “It has been destroyed by bureaucracy.” Recalling his visits to PTV Karachi, Sabzwari painted a bleak picture. “When I enter the studios, I literally cry. The corridors are empty. The infrastructure is number one, but unused.”

He also pointed out that much of today’s private television industry is staffed by people trained at PTV itself. “Even today, heads of departments in private channels are people trained at PTV,” he said, a reminder that the problem is not talent, but how it is being used.

Others caution against viewing PTV solely through the lens of decline. Actor-director Yasir Hussain challenged the tendency to measure the channel against its past. “If we only remember the dramas of the 70s, 80s and 90s, then we should just run them and call it Nostalgia TV,” he said at a recent event.

Hussain argued that PTV still enjoys the widest reach in the country through terrestrial broadcast, but fails to use that advantage meaningfully. “The drama slot with the biggest audience is not being treated seriously,” he said. “TRP can be generated anywhere.” He also questioned why quality continues to lag despite the facilities available. “We shoot on location, in heat, without facilities,” he said. “PTV has air-conditioned studios. They can make dramas twenty times better.”

From within the organisation, PTV officials say the criticism overlooks the channel’s broader mandate. Responding to concerns, PTV General Manager Amjad Shah said the broadcaster’s role goes beyond commercial entertainment. “PTV is a national channel. Our responsibilities are different,” he said.

Shah pointed to ongoing and upcoming projects, including Babu Ki Dulhanniyan, new plays by Asghar Nadeem Syed, Ramadan transmissions, religious programming, and large-scale concerts featuring artists such as Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, Ali Zafar, and Atif Aslam. “We are working according to today’s trends, while staying connected to our traditions,” he said.

At the same time, Shah acknowledged that commercial pressures have reshaped creative decision-making.“Earlier, directors had complete freedom,” he said. “Now, casting and glamour are dictated by sales. That’s where creativity suffers.”

Actor and writer Bushra Ansari highlighted another loss in this transition: music. “PTV has a treasure of music,” she said. “It hurts that it couldn’t be used properly.” Actor Hiba Bukhari, meanwhile, offered a more pragmatic reading of the industry. “Producers invest in what sells,” she said. “Only 20% of audiences want something different.”

She pointed to projects such as Kabli Pulao on Green Entertainment and Case No. 9 as proof that unconventional stories can still work, but only when producers are willing to take risks. “The producer has to be daring,” she said.

As debates around budgets, bureaucracy, and creative freedom continue, PTV finds itself caught between legacy and reinvention. The infrastructure exists, the talent has not disappeared, and the audience is still there. What remains uncertain is whether the institution can move quickly — and boldly — enough to meet a present that no longer waits for nostalgia.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ