Al Pacino might be among the most popular actors on the planet, but there is much more to the man who shaped some of cinema’s most fantastic characters. In his memoir Sonny Boy, Pacino finally lifts the privacy he protected for decades—even as fame followed him everywhere after The Godfather. The book offers a mix of honesty, reflection, and personal history that fans have waited years to read.

In many ways, Sonny Boy feels like an Al Pacino film on paper. The story begins in the South Bronx and rises all the way to Hollywood royalty. Most of the memoir focusses on his early struggles, and that alone makes it worth picking up. For years, Pacino’s personal life and creative process remained a mystery; this autobiography breaks that pattern, taking readers behind the scenes of the performances that shaped his long career.

If you didn’t know that during The Godfather, Pacino couldn’t drive, couldn’t speak Italian, couldn’t dance, and faced constant pressure from the studio for being “too unknown,” then this memoir will surprise you. He explains how his rough upbringing meant missing out on many things his friends took for granted. His parents divorced when he was two, his grandparents raised him while his mother worked to survive, and he dropped out of school before losing her in his early twenties—a loss he still describes as devastating.

Pacino also shares details about his acting method, shaped by years in the theatre and by mentors like Lee Strasberg, who pushed him to explore the Method style that later defined him. Few people know that Pacino also wrote and directed documentaries and even helmed a couple of feature films, or that he once fell into bankruptcy despite his fame. The book sheds light on these lesser-known chapters with surprising openness.

As the memoir progresses, Pacino spends less time on films and more on his personal interests and reflections. While this shift may feel slow to some readers, his stories about early encounters with Dustin Hoffman, Martin Sheen, and Robert De Niro are delightful. One anecdote describes how he and De Niro lived blocks apart in New York for years, yet somehow never crossed paths until much later.

Before starring in classics like The Godfather, Serpico, and Dog Day Afternoon in the 1970s, and Scent of a Woman, Carlito’s Way, and Heat in the 1990s, Pacino was part of a small neighbourhood gang where he briefly experimented with drugs and alcohol. His mother, like many strict parents of the 1950s and 60s, didn’t allow him out after sunset, which sparked a rebellious streak he now regrets. Ironically, that same spirit helped him channel raw energy onstage. At one point, he was even called “the next Marlon Brando”—a comparison that thrilled and terrified him, mainly because he later acted beside Brando in his breakout film.

Pacino was a late bloomer in cinema, landing The Godfather at 32—late by Hollywood standards. He explains how studio executives pushed for a taller, more famous actor, and how director Francis Ford Coppola fought to keep him. He names many friends and teachers who helped him rise before forty, and admits he survived more “lows than highs,” yet never let the setbacks erase his ambitions.

Two of his deepest regrets, he writes, were relying too heavily on a business manager who mishandled his finances and his long struggle to give up drinking, which nearly destroyed his career. He also gives careful attention to how he developed the energy behind his iconic lines and shares stories about the relationships he had over the years—many of which were strained by his intense commitment to acting.

The memoir includes personal photographs from his childhood, his theatre years, and later film sets, giving fans a visual timeline of his life. Sonny Boy does drift off track at times, much like Pacino’s unpredictable filmography, especially when he goes into long, philosophical reflections on fame and loneliness. Yet even those detours show a side of Pacino that rarely appears in interviews.

One of the strongest parts of the book is Pacino's look back at the roles he turned down, some because he didn't feel ready, others because he didn't understand the scripts at the time. He admits passing on a few films that later became major hits, but says he never regretted choosing roles "that scared him" because that fear pushed him to grow as an actor. This honesty gives the memoir a refreshing, human touch.

Another standout section explores how Pacino approaches failure. He talks about flawed performances, forgotten films, and moments when he felt his career slipping away. Instead of avoiding these topics, he leans into them, sharing what each setback taught him. His reflections on rebuilding confidence, especially in the early 1980s, when roles dried up, are some of the most inspiring pages in the memoir.

In the end, Sonny Boy works because Pacino writes the same way he acts-with intensity, humour, sensitivity, and a deep respect for craft. Even when the story wanders, the voice behind it remains warm and honest. For anyone curious about the man behind the iconic roles, this autobiography offers a rich, revealing look at a Hollywood legend.

A legacy worth celebrating

More than an actor who clawed his way into Hollywood, Pacino’s a full-blown American myth — a story of an outsider who didn't just enter the gates of an exclusive world but remade the place in his own image. Before Pacino arrived, the actors who dominated the industry were classic Hollywood alphas: tall, polished, and blue-eyed men who fit an established mold. Pacino fit none of it. Born in Bronx to working-class parents, he had no connections, no safety net, and no roadmap. What he had was hunger — the kind that starts fires.

In his early days, Pacino wasn't the man people lined up to watch; he was the one tearing their tickets. As a part-time usher in a small New York theatre, he watched audiences pour in to see other performers command the stage. Years later, those same types of crowds would pay to see him. That arc from usher to thespian is more than poetic. It's the blueprint of a man who started at rock bottom and reached the pinnacle through hard work.

Before The Godfather, Pacino was barely a name. Even director Francis Ford Coppola had to fight the studio for him. He was too short, they said. Too ethnic. Not charismatic enough. The wrong type of masculine. Hollywood wanted leading men who looked like they’d stepped off Mount Olympus. Pacino looked like he’d stepped off the subway. And yet, once he was on screen, he towered. He wasn’t the archetype with blue eyes; he was the man who could become anyone — a trait far more devastating.

Then came Michael Corleone. A role that didn't just announce Pacino — it detonated him into the culture. His performance across The Godfather and The Godfather Part II remains one of cinema's greatest studies in controlled intensity: a quiet young man curdling into ruthless power. That work alone could have secured a lifetime of respect. But Pacino didn't coast.

Through the 1970s, he turned in a streak few actors have equaled: Serpico. Dog Day Afternoon. …And Justice for All. Raw. Political. Electric. These were characters born from the New York streets he knew-flawed men pushed to the edge, men who vibrated with moral conflict and survival instinct. In a decade defined by anti-heroes, Pacino became the benchmark.

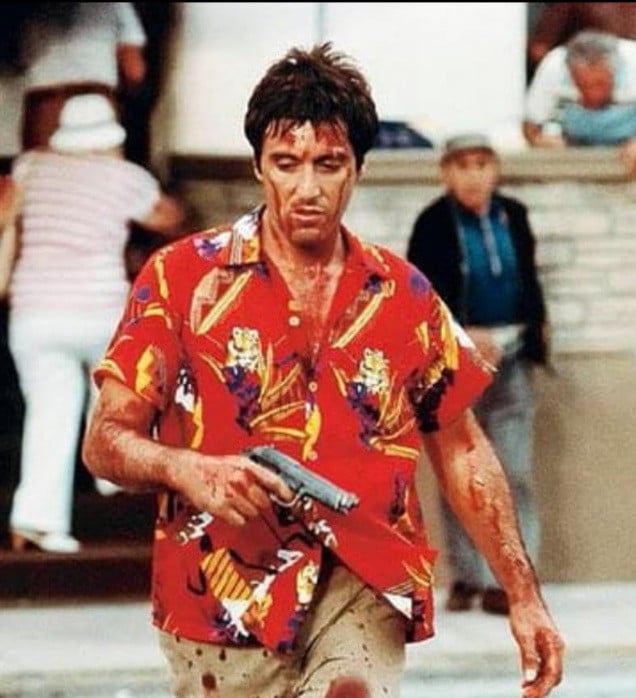

The 1980s brought a new wave of actors, a new tide of heartthrobs with the fresh gloss of Hollywood youth: Tom Cruise, Rob Lowe. Pacino countered with Tony Montana in Scarface, a performance so oversized, so operatic, so volcanic, it transcended the decade itself. Tony Montana wasn't just a character; he was a cultural thunderclap. Decades later, his lines still echo across hip-hop lyrics, posters, memes, and dorm room walls. It was Pacino proving, yet again, that when the spotlight shifts, he doesn't chase it-he wrests it back.

But the 1990s sealed his legend. Frankie and Johnny. Carlito's Way. Heat. Donnie Brasco. The Devil's Advocate. Any Given Sunday. A decade of roles that demonstrated what range looks like when stretched to its outer limit. And at the center of it, the performance that finally won him an Oscar: Lt Col Frank Slade in Scent of a Woman. Loud, shattered, theatrical, and deeply human-the type of role that only Pacino could yank into coherence.

But what's remarkable-and rarely said-is how often Pacino stumbled. His career dipped. He chose films that didn't land. Critics wrote him off more than once. Yet each time, he returned stronger. That resilience wasn't magic; it was Bronx-taught, theatre-forged, fight-for-everything persistence. Pacino didn't fear the dark alleys. He grew up in them. And whenever his career wandered there, he found his way back to the bright lights.

Even after the age of 60, when most actors tend to slow down, Pacino kept pushing. He played a corrupt detective opposite Robin Williams in Insomnia — cold, coiled. He was a manipulative mentor in The Recruit, an unexpectedly slick reinvention that left audiences gobsmacked. He paired up again with Robert De Niro in Righteous Kill, then again in The Irishman — released on a streaming platform, an idea unimaginable when Pacino started in an era worshipful of the big screen.

Along the way, he directed and produced films and documentaries, but he's not celebrated for his behind-the-camera work. He's celebrated for being the kind of actor who sets the bar for everyone else. Even in his misfires, there's a fearlessness most performers spend their careers trying to find.

Al Pacino may not be the kind of busy actor he was in his youth, yet when he does appear on screen, he still packs a punch. Whether playing a Nazi hunter driven by vengeance in Amazon's Hunters or taking on Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, Pacino continues to surprise his audience, embracing challenging material rather than easing into retirement.

The Pacino story isn't one of success alone, but one of defiance, of building a career not on looks, not on pedigree, but on the acting that ricochets through decades. He proved that greatness needn't require perfection, just the courage to rise, fall, and rise again. And that's why Al Pacino's legacy endures. It is something worth rejoicing over.

Omair Alavi is a freelance contributor who writes about film, television, and popular culture

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the writer