Pakistan is home to approximately 20,000 Sikhs. A small minority compared to the millions who lived in Punjab before Partition. There are roughly 200 historical Sikh shrines noted by Iqbal Qaiser in Historical Sikh Shrines in Pakistan. The Pakistan Sikh Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee (PSGPC) currently manages around 21 gurdwaras, according to their website. In these sanctuaries, kirtan is the heartbeat of Sikh liturgical life.

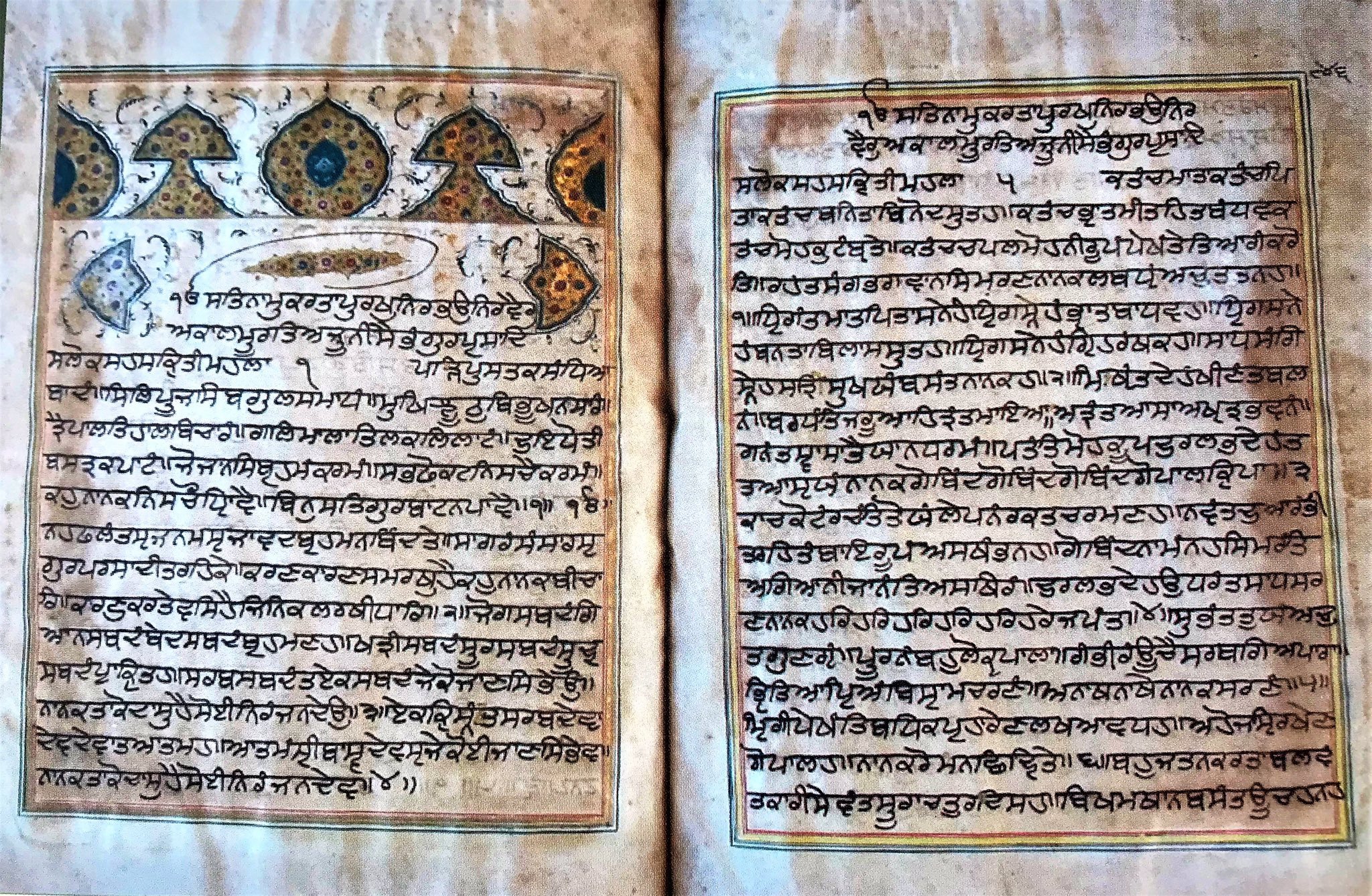

The Sikh Gurus made music central to worship. The Guru Granth Sahib, Sikhism’s scripture, stands out among world religious texts, which are arranged by Raags, which are the melodic frameworks in Indian classical music. Gurinder Singh in The Making of Sikh Scripture notes there are 31 main raags and 29 sub-mixed raags in the text. Out of 1,430 pages, the arrangement of 1,343 according to Raag gives Sikh scripture an inherent musical quality. Its worship is inseparable from music.

Kirtan keeps alive the tradition of singing the Holy Scripture and it has thrived through centuries of devotion, change, and adaptation. The journey that starts with ten Gurus, the Rababi, Ragis, and Dhadhi custodianship, includes the violent dislocations of Partition and its fragile survival in today’s Sikh minority of Pakistan.

Through Stuart Hall’s “being” and “becoming”, Sikh liturgical music in Pakistan emerges as both continuity and change. Being is the unbroken devotion to Gurbani, the centrality of singing scripture.

Becoming means adapting. It’s about replacing traditional musical instruments, using digital tutorials instead of ustads, and drawing on mentorship from the diaspora that is reshaping how music is taught. This duality shows identity as dynamic, not frozen. Kirtan in Pakistan is not a relic but a process: fragile, inventive, and forward-looking.

Gerald Barrier, in The Sikhs and Their Literature, points out that the Gurus stressed kirtan as more than music; it is a spiritual practice. Its purpose is to attune the soul with the Infinite. To bring peace, joy, and concentration of mind. To remove worldly vices like ego, anger, greed, and attachment. To act as a ladder to salvation.

Guru Nanak (1469–1539), the founder of Sikhism, initiated the tradition of Gurmat Sangeet. Accompanied by his Muslim companion Bhai Mardana, who played the rabab, Guru Nanak sang his compositions in ragas. He made kirtan a daily practice at Kartarpur. Each day, there were morning and evening sessions for the congregation to join.

Guru Nanak composed 974 hymns in 19 ragas, as noted by Gobind Singh Mansukhani in Indian Classical Music and Sikh Kirtan. He popularised ragas like Asa, Suhi, and Tilang in devotional music. His mixed approach combined Hindu and Muslim musical styles reflecting the diverse spirit of his time.

Guru Angad (1504–1552) continued the tradition of Asa-di-Var kirtan in the early mornings. He composed in ragas like Basant and Malar, using seasonal symbolism to convey spiritual truths. Guru Amardas (1479–1574) emphasised the Anand Sahib, which celebrates bliss through singing God’s praises. He composed 907 hymns in 17 ragas.

Guru Ramdas (1534–1581) was a talented musicologist. He added 11 new ragas to the repertoire. Some of these include Devgandhari, Jaisri, Todi, and Kalyan. His compositions, such as the Lavan in Suhi raga, recited during Sikh weddings, remain central to Sikh liturgy.

Guru Arjan (1563–1606) compiled the Adi Granth in 1604. This was the first Sikh scripture. It includes hymns from the Gurus and saints of Hindu and Muslim traditions. He introduced chowkies, or five daily music sessions, at Harmandir Sahib (The Golden Temple).

Guru Arjan also trained amateur "ragis", reducing dependence on professional rababis. He himself was an accomplished musician who devised the bowed instrument "sarinda".

Guru Hargobind (1595–1644) supported a new group of musicians known as “Dhadhis.” They sang heroic ballads while playing the dhadh (a small hand-drum) and the sarangi. This martial music inspired Sikhs during the Guru’s militarisation phase. Guru Tegh Bahadur (1621–1675) composed 116 hymns in 15 ragas and introduced the raga Jaijawanti.

The tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh (1666–1708), was a patron of poets and musicians. He composed in 19 ragas, some distinct from those in the Guru Granth Sahib, and encouraged both classical and folk musical forms. He renamed the Adi Granth as the Guru Granth Sahib, giving it eternal Guruship.

The Guru Granth Sahib prescribes ragas and their variants. These include, to name a few, Sri, Asa, Gauri, Suhi, Bilawal, Ramkali, Maru, Basant, Malar, Prabhati, and Jaijawant. Musicians perform each raga at a specific time — morning, afternoon, evening, or night — and express particular moods, known as rasa.

Classical Indian aesthetics identifies nine rasas (emotions). The Sikh Gurus added a tenth rasa, Nam Rasa or Amrit Rasa, the bliss of experiencing the Divine Name. Ragas in Gurbani express shringar (love), veer (heroism), and shant (peace). But the highest rasa is Amrit rasa, the sweetness of remembering the Divine.

Musicians sing seasonal ragas such as Basant (spring) and Malar (rainy season) at appropriate times of the year. The ragas show the universal nature of Sikh scripture. They blend Hindustani styles with elements from Karnataka and folk music traditions.

Mansukhani identifies six styles of Sikh kirtan. Music-oriented kirtan emphasises raga and tala over text. Instrument-oriented kirtan is where musical accompaniment dominates. Hymn-oriented kirtan focuses on the clear delivery of Gurbani, which congregations highly value.

Discourse-oriented kirtan includes explanation and commentary. Demand-oriented kirtan consists of popular hymns sung by request. Congregational singing is where the sangat joins collectively. Among these, hymn-oriented kirtan is considered the purest form, as it conveys the Guru’s message with clarity and devotion.

Gibb Schreffler, in Musical Traditions of the Punjab, highlights traditional Sikh Kirtan instruments. These include stringed ones (Tat vad): rabab, sarinda, taus, and later, the sitar. Percussion (Avanaddh vad): pakhawaj, mridang, tabla, dholak, dhadh. Wind (Sushir vad): bansuri, flute, harmonium (introduced in the colonial period). Metallic (Ghan vad): chimta, cymbals, khartal. Clay (Nad vad): ghatam, jal-tarang.

Jagir Singh in Sikh Musical Tradition notes that Gurmat Sangeet uses classical taals; for example, teen taal, ek taal, and Jhaptaal taal. Originally rendered in dhrupad style, it is solemn and meditative. Later, khayal elements were adopted for their flexibility and great ornamentation. Over time, folk instruments and desi taals like dholak, jori, and taals like dadra and keherva blended with classical precision.

The first custodians of Sikh kirtan were the Rababis. These were Muslim mirasi musicians, and they were initiated by Guru Nanak. Families such as Balwand–Satta and Babak–Chatra transmitted Gurbani through generations. Rababis performed in Sikh shrines and interfaith gatherings. They reflect Punjab’s shared musical ecology, as noted by Regula Qureshi in Muslim Devotional Music in South Asia.

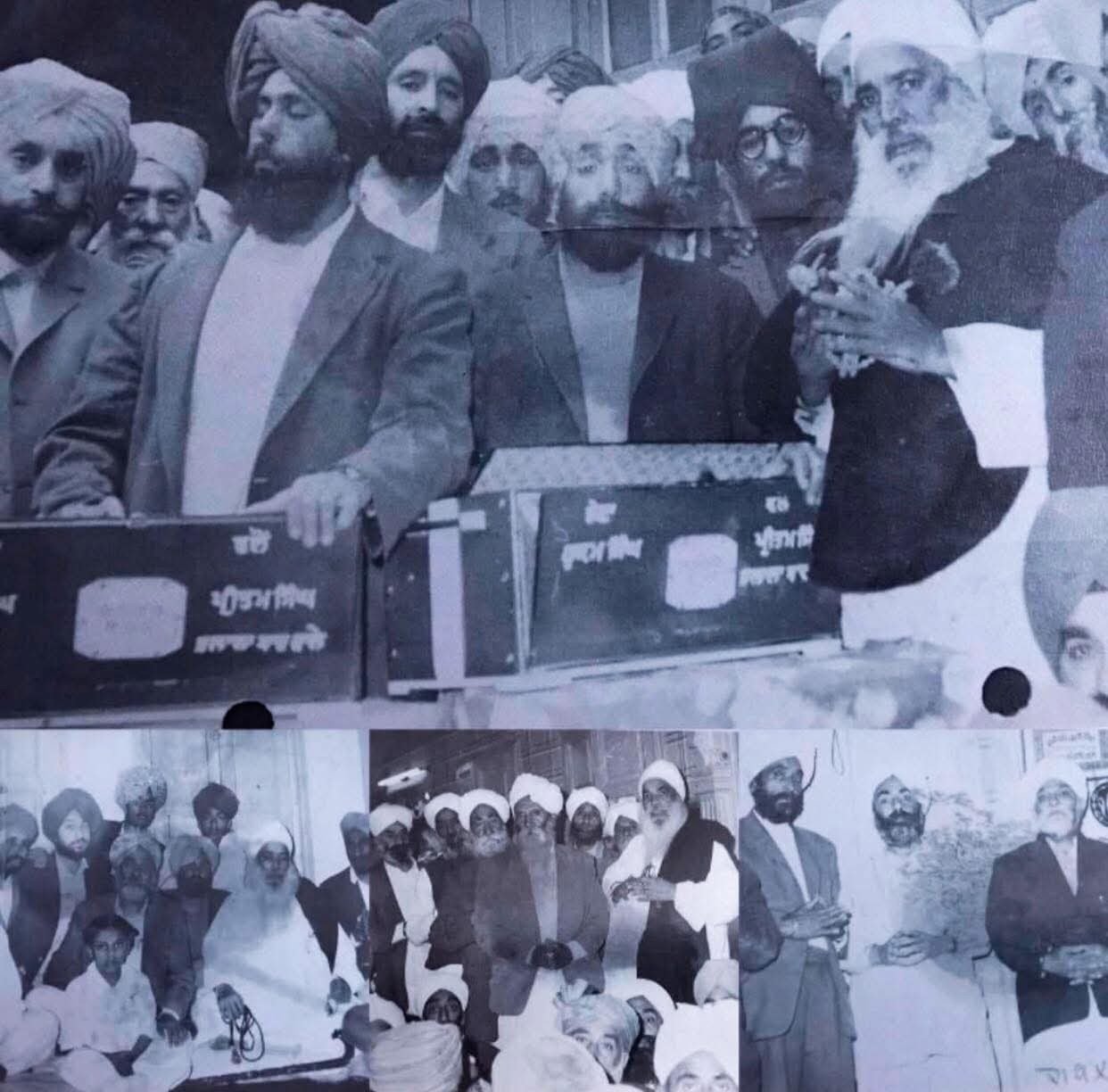

Many migrated to Pakistan after Partition, and the tradition nearly vanished. Today, a few descendants remain, like the 13th-generation Rababi, Ustad Moeen Ahmed Chand. However, their role in regular liturgical kirtan is almost gone. This absence is one of the sharpest cultural losses Partition inflicted. Ragis, introduced by Guru Arjan, are Sikh musicians who sing kirtan in gurdwaras. They form the backbone of Sikh kirtan today.

The partition displaced people and disrupted guru-shishya lineages. It also scattered manuscripts and destroyed instruments. Many Sikh ragis migrated to India; many rababis lost their congregations. The Evacuee Trust Property Board Pakistan (ETBP) records show abandoned gurdwaras where kirtan ceased for decades.

Pre-Partition, kirtan followed the guru-shishya parampara: oral, immersive apprenticeship. After 1947, teaching in Pakistani Sikh households moved to a family-based system due to broken lineages.

Diaspora mentorship, with ragis from the UK, Canada, and India visiting Pakistan, is evident. Digital tutorials, with youth learning via YouTube and WhatsApp, are present. Hall’s becoming is visible here; pedagogy adapts to global networks, sustaining continuity through innovation.

The most noticeable change in instruments was that the harmonium, a European reed organ from the 19th century, took over. It replaced string instruments such as the rabab, sarinda, sarangi, dilruba, and taus. The tabla replaced the pakhawaj, mridang, and jori.

Today, the harmonium and tabla dominate. This raises questions about temperament and microtonality. The harmonium fixes pitch, which somewhat limits raag fidelity. Ethnomusicologists like Qureshi argue that this alters the very ontology of Gurbani music.

With time, simplified, adapted raags, added folk melodies, and adjusted shabads for better participation in the congregation. Transmission shifted from professional lineages to family teaching and later to cassette and digital media. These adaptations show what Hall calls negotiation, not betrayal. They help to ensure survival in new conditions.

Nankana Sahib in Pakistan has a daily liturgy. It becomes lively during Gurpurab festivals. Small training programmes for youth ragis have started. One example is music classes at Bhai Joga Singh Khalsa Dharmic School in Peshawar. Panja Sahib in Hasan Abdal is pilgrimage-centred kirtan; ragis perform for visiting jathas.

Lahore's Dera Sahib shrine, close to Badshahi Mosque, is alive with kirtan. It sounds blended within a diverse religious setting. Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa's smaller Sikh communities keep survivalist kirtan alive. They often mix folk tunes with Gurbani.

Repertoire and Liturgical Settings include Daily Nitnem of Japji Sahib, Asa di Var, Sodar, and Sohila. Festival Kirtan features Gurpurabs and Baisakhi. It includes longer sessions, visiting ragis, and Akhand Path openings.

Gurpurabs at Nankana Sahib and Baisakhi at Panja Sahib make small communities celebrate on a global scale. Diaspora Sikhs often provide training workshops, bring recordings, instruments, and financial support. Live streams and WhatsApp share these performances worldwide. This makes Pakistan’s kirtan part of a global network. The continuity is fragile but real, anchored in the commitment to Gurbani as sung scripture.

Sikh theology supports gender equality; women are equal in rights, practice, and participation. Leadership roles, like being the main ragis or leading kirtan, are rare. This is especially true in traditional or conservative congregations.

Recently, more women have become aware of music opportunities. They train in instruments or vocals, join youth groups, and take turns leading kirtan, in women’s gatherings which may include men. Their voices are often part of a chorus rather than solo leadership in large festival settings.

The community debate goes on. Some elders support traditional gender roles. But younger Sikhs push for more female leadership in liturgical music. They point to the Gurus’ teachings on equality. Local practices in Lahore and Sindh show both limits and slow change. Women are asserting their roles through hands-on work, teaching, and digital platforms.

Pashaura Singh, in Re-imagining South Asian Religions, points out that liturgical practice in Pakistan has its limits. Gurdwaras are run by the ETPB, hence not fully by the Sikh community. The minority status of Sikhs under Pakistani law limits their rights. Security and access issues limit free movement.

Kirtan acts as a hidden transcript under these conditions. It quietly shows resilience and asserts Sikh identity in a society where they are a small minority. There is demographic decline, challenges to continuity, and migration. Also there has been a loss of traditional instrument makers, along with security and funding constraints.

Festivals, diaspora support, grassroots teaching, and digital connectivity all provide pathways for renewal. Preservation of the sacred core will remain essential, but adaptation will also be necessary. Sikh music in Pakistan is more than a set of hymns. It is testimony to survival, a sign of human will to keep singing even when history tried to still the voice.

Hearing Gurbani kirtan in Pakistan today brings the past to life. It reflects the present and hints at a future where the songs will go on. It is to recognise music not only as revelation but also as resilience. The hymn still carries on.

Brian Bassanio Paul is a music enthusiast whose expertise lies at the intersection of music business, artist development, music appreciation, and cultural studies. He can be reached at brian.bassanio@gmail.com and on LinkedIn @brianbassanio

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the author