I was 19 when I dragged myself — half-hearted and unimpressed — to the compulsory Breast Cancer Awareness seminar at Fatima Jinnah Women University in Rawalpindi. I was just a young undergraduate trying to make it through the day. Little did I know, that seminar would save my life, two decades later.

Something about it struck a chord. Amid the dull hum of mandatory attendance, a spark lit inside me. I remember walking out with a silent vow: I will check myself. Regularly. It was the first time I had thought of self-care as an act of survival, not vanity. Over the years, I kept that promise to myself. Anytime I felt a lump or change, I consulted a doctor. It was always dismissed — just a fibroid, just a skin issue. Nothing serious. Until December 2023.

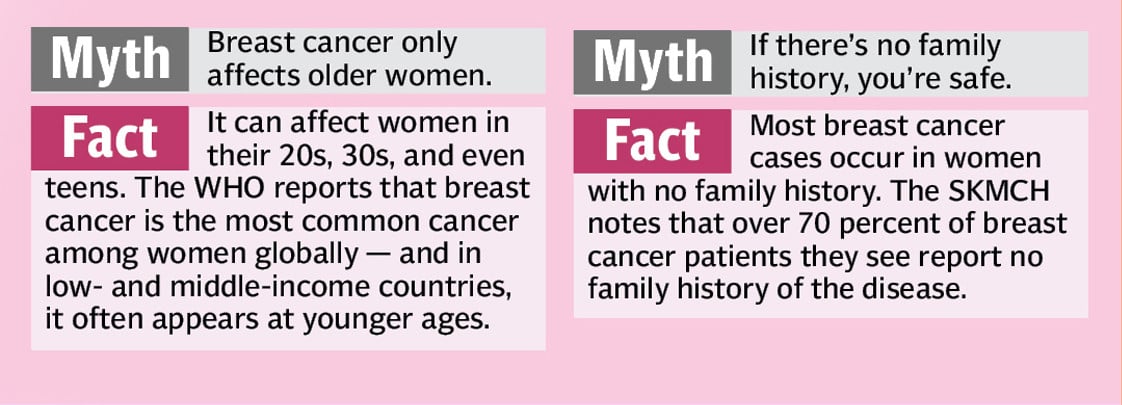

I was 40 years old when I felt a 3cm lump — different this time. Larger. Harder. Less dismissible. Still, I told myself it was probably nothing. I had no family history of breast cancer, so it felt unlikely. But I saw a surgeon at the hospital where I was working at the time. She suggested a mammogram, and after it was done, the radiologist looked me in the eye and said: “Don’t leave this without a biopsy.”

The wait for the biopsy result was long and agonising. I had opted to receive the report online, and when I opened the document on a quiet Sunday afternoon, one word hit me like a tidal wave: carcinoma. I didn’t know what “cribriform carcinoma” meant — but I knew what carcinoma was. I was staring at the word “cancer.” My hands trembled. I called my sister WHO’s a doctor, and burst into sobs. My sister tried to reassure me. “It’s a slow-growing cancer,” she said gently. “And breast cancer is one of the most treatable types.” But logic rarely reaches you when you’re drowning in the panic of hearing the word cancer.

Soon, I found myself at the hospital almost daily — this test, that scan, one procedure after another. Each day felt like a new chapter in a story I hadn’t agreed to write. Further investigations confirmed the specifics: I had ER-positive, PR-positive, and HER2-negative breast cancer. My oncologist explained that this type is considered less aggressive and generally easier to treat than triple-negative or HER2-positive cancers.

Because of the tumour’s size and characteristics, the treatment plan began with upfront surgery. An MRI, CT scan, and additional imaging were ordered to help the surgeon get a clearer view of the tumour and surrounding tissue. I tried to project confidence — held my chin up, smiled, cracked jokes. Looking back, I realise I should have asked for more support. But I didn’t. I just wanted to be over with the surgery as soon as possible.

What scared me the most was the possibility of losing part of my breast. The tumour was located directly beneath the areola, and I was warned that this could make breast conservation difficult. The thought broke me in ways I couldn’t explain. A breast is not just skin and tissue — it is tied to how you see yourself as a woman, to intimacy, to the simple act of feeling WHOle in your own body. I imagined standing in front of the mirror and seeing a flat scar where my breast had been, and I wondered if I would ever feel like myself again. It wasn’t vanity—it was identity. It was dignity. It was the fear of carrying a loss that no one else could see but I would feel every single day. But my surgeon—an expert in breast-conserving procedures — reassured me that saving the breast was possible. And he did. He not only preserved it, but did so with remarkable aesthetic care. For that, I will always be grateful.

After the surgery, my oncologist recommended the Oncotype DX test — an advanced, but very expensive diagnostic tool that most people in Pakistan cannot afford. It’s only suggested for women with ER/PR-positive, early-stage breast cancer, and not everyone qualifies for it.

The test evaluates whether your specific type of cancer is likely to benefit from chemotherapy. A score below 20 usually means that chemotherapy will not be effective — and might be unnecessary. When my results came back, my score was zero.

It was a huge relief, but also a reminder of how privileged I was to even access this test. My husband supported me without hesitation, and together we decided to go ahead with it. But I couldn’t stop thinking about the women who can’t. Women, who have no access to this option, often end up going through several rounds of chemotherapy.

The recovery from surgery was smoother than I had expected. Surprisingly, I physically bounced back faster than my husband had after his gallbladder surgery. Maybe it was the location of the incision — or maybe it was adrenaline, denial, or sheer determination. I did have a drain attached to the surgical site, and while it wasn’t painful, it was definitely annoying. It tugged at my skin and reminded me constantly of what my body had just been through. Still, the days passed. A week later, the drain was removed, and with it came a sense of profound relief.

Everyone around me was celebrating the ‘good news’— the successful surgery, the zero Oncotype score, the fact that I didn’t need chemotherapy, and that none of my lymph nodes were affected. But inside, I felt... quiet. Numb. As if I had been holding my breath for months and still couldn’t exhale.

The hardest part, I realised, wasn’t always the treatment —I t was what came after, when the dust settled and I was left alone with the weight of everything I’d been through. What I was facing was depression — not ordinary sadness, but the kind that stopped me from getting out of bed, that kept me from feeling joy in the fact that I had survived. It hit both my brain and my body, even after bravely fighting the battle.

And it shook my confidence, even as a clinical psychologist and psychotherapist who helps others. I didn’t know it then, but naming it and confronting it would later become part of my healing — teaching me that strength also means allowing yourself to struggle. But there was no time to process those feelings fully — because just as I was beginning to catch my breath after surgery, the next phase began: radiation.

I hated that they had to mark my body with tiny permanent tattoo dots — to ensure the treatment hit the exact location every time. It felt invasive, like a scar I hadn’t chosen.

Radiation itself was exhausting. It drained me in ways I hadn’t anticipated. The fatigue crept in slowly but settled heavily — and yet, people around me, including some doctors, dismissed it. “At least you’re not going through chemotherapy,” they said, as if radiation should somehow feel easy. But bone-deep fatigue from radiation is real, common, and often unacknowledged. For me, it wasn’t just physical tiredness — it was the kind of weariness that seeped into my bones, making even simple tasks feel overwhelming.

Slowly, the skin at the treatment site began to burn. At first, it was just irritation. Then it turned raw —angry, painful — like a second-degree burn. My doctor had already prescribed ointments to manage the side effects, and thankfully, she was on top of it before it got worse. But even with care, it felt like my skin would never heal. The pain lingered. Some days, it felt like it would never go.

I felt like I was supposed to be happy — that I had finished treatment and that I was past the worst. But instead, a strange sadness slowly seeped in. I was sad. I was angry. Why did this happen to me?

People kept reminding me how lucky I was. And I knew I was—I hadn’t needed chemo, my lymph nodes were clear, the surgery had gone well. But I couldn’t explain why I still felt so heavy. I was depressed— shocked, drained, unable to feel the joy everyone expected me to feel. But in admitting it, I began to understand that healing is never just physical. Why wasn’t I happy that it was over? Because recovery of the mind takes its own time, and that realisation later made me more compassionate toward the patients I support.

Soon after, I was put on a ten-year course of Tamoxifen, a hormone therapy meant to reduce the risk of recurrence. It is often described as an “easy” treatment, but it comes with its own hidden burdens — thinning hair, skin changes, lingering exhaustion, nausea, and menopause-like symptoms. For me, the side effects eventually settled within a year. But that first year was a reminder that even after treatment ends, your body and mind are still catching up.

Over the next year and a half, my body slowly began to recover. The fatigue that once felt like a heavy fog became more manageable — especially after I began regular exercise. Movement, even gentle at first, became a turning point. It didn’t just help my body; it helped me feel like myself again.

Breast cancer changes you — physically, emotionally, and even spiritually. But it also sharpens your instincts, deepens your empathy, and teaches you the quiet strength of survival. I’m still healing, in more ways than one. But I’m here. And I’m paying attention — to myself, to others, and to the life I almost took for granted.

Life as a survivor

Life after breast cancer gave me a new purpose. Today, I’m working on the Moving On After Breast Cancer (ABC) clinical trial at the Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning. This trial is happening right now across Pakistan, funded by the UK’s National Institute of Health and Care Research and run in collaboration with the University of Sheffield and the University of Manchester. It is the first of its kind in the country to focus on the emotional recovery of breast cancer survivors.

For me, it’s more than research — it’s personal. I know what it means to live through the silence, the fear, and the hidden struggles after treatment. That’s why I want other women to have the support I wish every survivor could receive. Women who take part in the trial will receive ongoing check-ins, information, and guidance, and some will also have access to therapy sessions developed especially for breast cancer survivors in Pakistan. By joining, women not only find support for themselves but also help build a future where no survivor in Pakistan is left to cope alone.

Mental health matters

Depression and anxiety are common in breast cancer survivors — studies show that up to one in three women experience depression and nearly half report significant anxiety. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), mental health is a critical but often neglected part of cancer care. Research also shows that untreated depression and anxiety are linked to higher mortality, greater disability, and lower quality of life, even years after diagnosis. Emotional recovery is just as important as physical healing.

Coping with loss

In Pakistan, many women are still diagnosed late, and mastectomy (full breast removal) becomes the only option. According to Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital (SKMCCH), most breast cancer cases in the country present at advanced stages, when breast-conserving surgery is no longer possible. The WHO also notes that breast loss can have lasting effects on a woman’s mental health, body image, and confidence. Yet recovery is possible — physically and emotionally. Losing a breast does not mean losing your worth.

Why awareness matters most in Pakistan

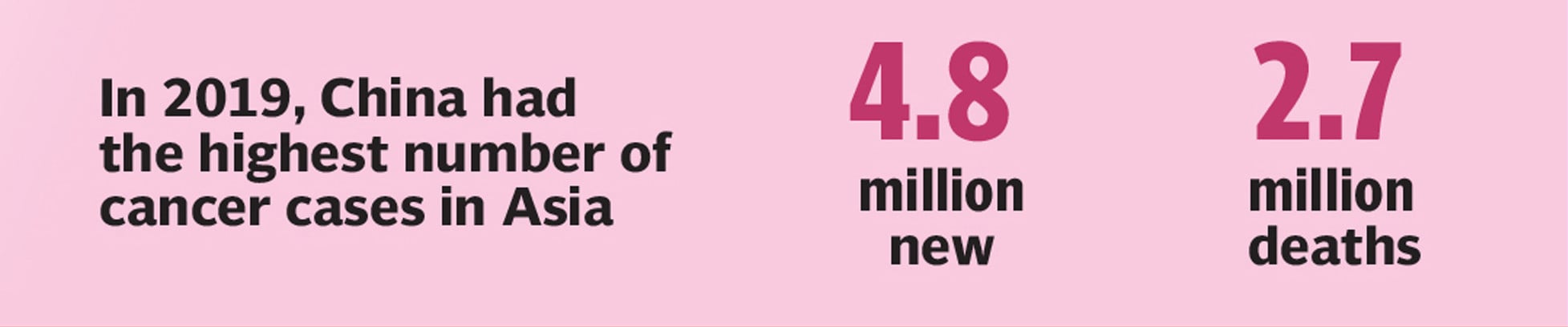

Catching breast cancer early is the only proven way to increase survival — the WHO notes that survival rates can double when breast cancer is detected at an early stage. But in Pakistan, most women are diagnosed late. According to SKMCH, the majority of breast cancer cases in the country present at advanced stages, often because women don’t know what to look for, or feel too afraid or ashamed to speak up. Awareness changes that. It helps women notice changes sooner, act faster, and seek treatment before it’s too late.

The writer is a clinical psychologist, health communication specialist, WHO works at Pakistan Institute of Living and Learning, where she contributes to research aimed at improving the lives of breast cancer survivors. She can be reached at ahlam.tariq@pill.org.pk

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the writer.