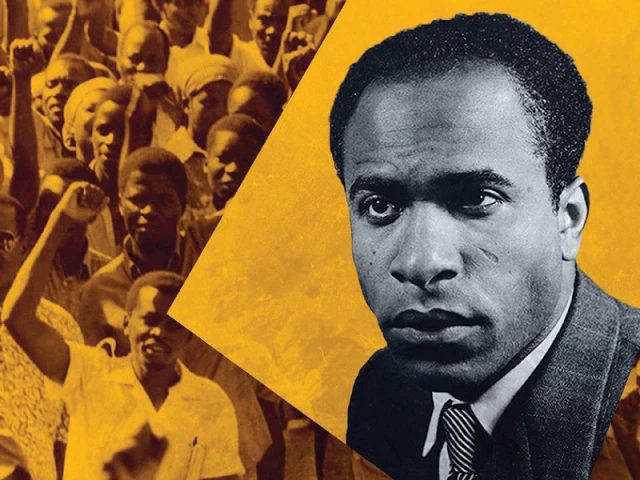

Remembering Algeria's Frantz Fanon 100 years after his birth

French psychologist worked to end colonialism

Frantz Fanon is regarded as a crucial figure of early anti-colonial and anti-racist theory. For Algerians, he is one of the heroes of the country's struggle for independence.

Yet his role during the war against France and his writings remain largely unknown to a wider public, reports DW.

July 20, 2025, marked the 100th anniversary of his birth. Fanon was not granted a long life: At just 36, he died of leukemia in 1961 without ever witnessing Algerian independence, a goal he devoted his life to.

His work is "a reflection on the concept of solidarity, understanding what solidarity means in a moment of war, of resistance," Mireille Fanon Mendès France told DW. She is Fanon's eldest daughter and co-chair of the international Frantz Fanon Foundation.

She says she barely knew her father and retains few childhood memories of him, but as a teenager, she immersed herself in her father's literary work.

Fanon's writings made it clear that the struggle for Algerian independence not only benefited Algeria, but was also about African unity. "And this African unity is still not there," his daughter explains.

In her Paris apartment, Alice Cherki goes through old documents from her youth during Algeria's war of independence against France: "I knew then that it was colonialism," she recalls. Now 89, she knew Frantz Fanon well. She worked alongside him in the 1950s as an intern at the psychiatric clinic in Blida, Algeria.

Fanon was the head of the psychiatric department and not only cared for the sick but also helped Algerian nationalists. "We took in the wounded, the fighters who came here," Cherki said. Fanon set up a supposed day clinic within the hospital, only for show. In reality, he secretly took in the wounded and those who needed to recover, Cherki told DW.

Committed to the cause

Born in the French colony of Martinique, Fanon grew up in a French colonial society and was deeply influenced by his experiences: He volunteered for World War Two for France at the age of 17. As a Black man though, he experienced daily racism in the French army. After the war, he studied medicine and philosophy in France and later moved with his wife Josie to Blida in French-Algeria, where he became chief physician of the psychiatric clinic.

From the beginning of the war in 1954, Fanon was helping Algerian nationalists while continuing to work as a psychiatrist. He established contacts with several officers of the National Liberation Army as well as with the political leadership of the National Liberation Front (FLN), especially its influential members Abane Ramdane and Benyoucef Benkhedda. From 1956 on, he was fully committed to the "Algerian cause."

Fanon wrote some of the most influential texts of the anti-colonial movement, like his early work Black Skin, White Masks about the psychological effects of racism and colonialism on Black people.

His most important book though was The Wretched of the Earth where he focuses on revolutionary action and national liberation. The book was published with a foreword by Jean-Paul Sartre shortly before his death in 1961.

On July 5, 1962, Algeria gained independence after an eight-year armed struggle against the then-colonial power, France. Historians estimate the number of Algerian deaths at 500,000; according to the French Ministry of the Armed Forces, approximately 25,000 soldiers lost their lives.

Anissa Boumediene is a writer, lawyer, and former First Lady of Algeria. She was the wife of President Houari Boumediene, who ruled the country from 1965 to 1978. "Frantz Fanon is part of Algerian history. He defended independence. He was truly an infinitely respectable person," she told DW.

Two new films - Fanon by Jean-Claude Barny, released in April 2025, and Frantz Fanon by Algerian director Abdenour Zahzah, released in 2024 - are intended to keep his memory and his anti-colonial theories alive.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ