“It was in the early 2000s that my daughter decided to move to the US where her father lived, to finish her high school,” recounts Fareeha Mirza*, a teacher in her 50s, her temples graying, her eyes soft brown.

'Life in Karachi was getting stifling for her as a 15-year-old being pestered by her mother to dress according to what area you are in Karachi — cover up and drape appropriately in varying shades of cultural acceptance and norms that we have created for ourselves in our metropolis.'

“When she left, I was left alone in our apartment. My parents lived separately in their apartment not far from our rented 2-bed in an upper middle-class residential building in Clifton. One thing was to miss her, with the depression and loneliness that followed. However, the more difficult part was to create the impression of not living completely alone. A single woman in our society is treated differently from a single woman with a daughter or a single woman with a son, as well as a single woman with a son and daughters. Let’s be honest, us Pakistanis are way too judgmental for our own good. We instantly form opinions about others, and mostly they are negative, as we live in our own holier-than-thou bubbles.

“Also, let’s not pretend that it doesn’t matter to those being judged, it certainly does — the heads being turned around, the nudges, smirks, and stares by women. The lingering looks by single and married men in the neighbourhood, in which case their mothers and sisters want to keep you at a distance, while their wives become insecure and sometimes even look a bit hostile.

I decided to keep a low-profile. The first thing I did was to dress down a bit. Try and deliberately look a little dowdy. Second, I made sure to step out and return home at decent hours. I stopped going to weddings which begin and end late and from where I would have to return home looking like a Christmas tree at late hours. I didn’t want to give the wrong impression, everything should be and look kosher.

“I used to read the news in those days as a part-time stint and sometimes return home with make up and a jacket on, but stopped doing that also when one neighbourhood gentleman, let’s call him Mr Bored-With-His-Marriage, who after politely greeting me when I returned home once, suggested that instead of news reading, I should model! I started to clean my face before I left the studios. Also, I put the jacket in the car on a hanger and draped a dupatta around my collared shirt. Now this to me is the worst form of encroachment on one’s personal space. But the average Pakistani doesn’t know about its existence.

“An electrician who came to the house a few times taught me another lesson. Seeing me alone in the house when he fixed a bulb or board, he actually had the audacity to suggest that some ‘madam’ whose house he worked in shared her problems with him. So he had become close to her, and I should feel free to do so, if I needed a friend. I was shocked, boiling, enraged, scared, and trembling all at the same time. I got his money out and mustered up the courage to politely tell him to leave whether the work was done or not.

“Later I bought a big pair of men’s shoes and slippers and kept them prominently visible in the house before any repairman arrived. I also learned that with dry cleaners etc where they need receipt on names, one must always brazenly declare that you are a “Mrs” and then give them a man’s name, never your own, or they tend to get fresh, quite unnecessarily.

“After many of years of calculated living, it so happened that I began to take care of a little boy from a humble family. It was an impulsive decision but worked wonders for both of us. I pay for his education and grooming expenses. I am like a foster parent to him but he goes home every evening after spending the day with me, doing homework, watching TV or playing in the house or outside with the building kids. This has been my life for the past seven years, in which both our lives have transformed. While he is on the fast track to becoming the first educated person in his family, I live alone yet I don’t feel depressed, bored or lonely. The biggest thing to happen in my life is that the acceptance level in my current building is of a family. I am respected, accepted and treated like a family or to be more precise, a woman with a family. There is a mountain of difference compared to me living alone and now with this little boy always being with me. It is hard to explain the difference in people’s attitudes and what I feel. But there it is and it is real. I am now seen and I am heard respectably. Even though I have basically remained the same person through the years, the presence of a little boy with me has changed how people see me in their warped heads. When I am visiting my daughter and people don’t see me around in the parking lot, they call up and ask where and how I am, and this is not a development post the sad demise of Humera Asghar Ali. In conclusion, I would say who knows what pressures she had, what kind of rejections and exceptions she went through while looking for acceptance as an actor, a woman and a person. May she rest in peace.”

Fareeha’s story is a deeply personal narrative of a single woman in Karachi struggling through the Pakistani society by living alone since the early 2000s. It chronicles the daily challenges she tackled to avoid judgment, harassment, and isolation — from altering her wardrobe to fabricating the presence of a man in the house. It ends with a poignant reflection on how the mere presence of a foster child changed her social acceptability, highlighting the disturbing reality that women are only respected when tethered to a "family."

While Fareeha’s is just one voice, there are countless others echoing the same struggles. Take Areeba Khalid, for instance — 27-year-old software engineer who moved to Karachi from Multan for a well-paying job opportunity. She envisioned freedom, growth, and a life built on her terms. Instead, she found herself drawing curtains too early, whispering on phone calls, and hesitating before inviting a female friend over, fearing the neighbours’ gaze or worse, the landlord’s wrath. Living alone, it turned out, came at a price to her peace of mind.

Across Pakistan, many women who choose to live alone, whether for work, education, or independence, face an unspoken resistance. These women are not just fighting for their careers or dreams; they are silently fighting to exist in spaces not designed to accept them as independent individuals. They are questioned, judged, and often harassed.

Judged for choosing independence

In a deeply patriarchal society, a woman living on her own is often seen as a deviation from societal norms. While men are presumed to be independent, women who break the family-centric living arrangement are met with suspicion.

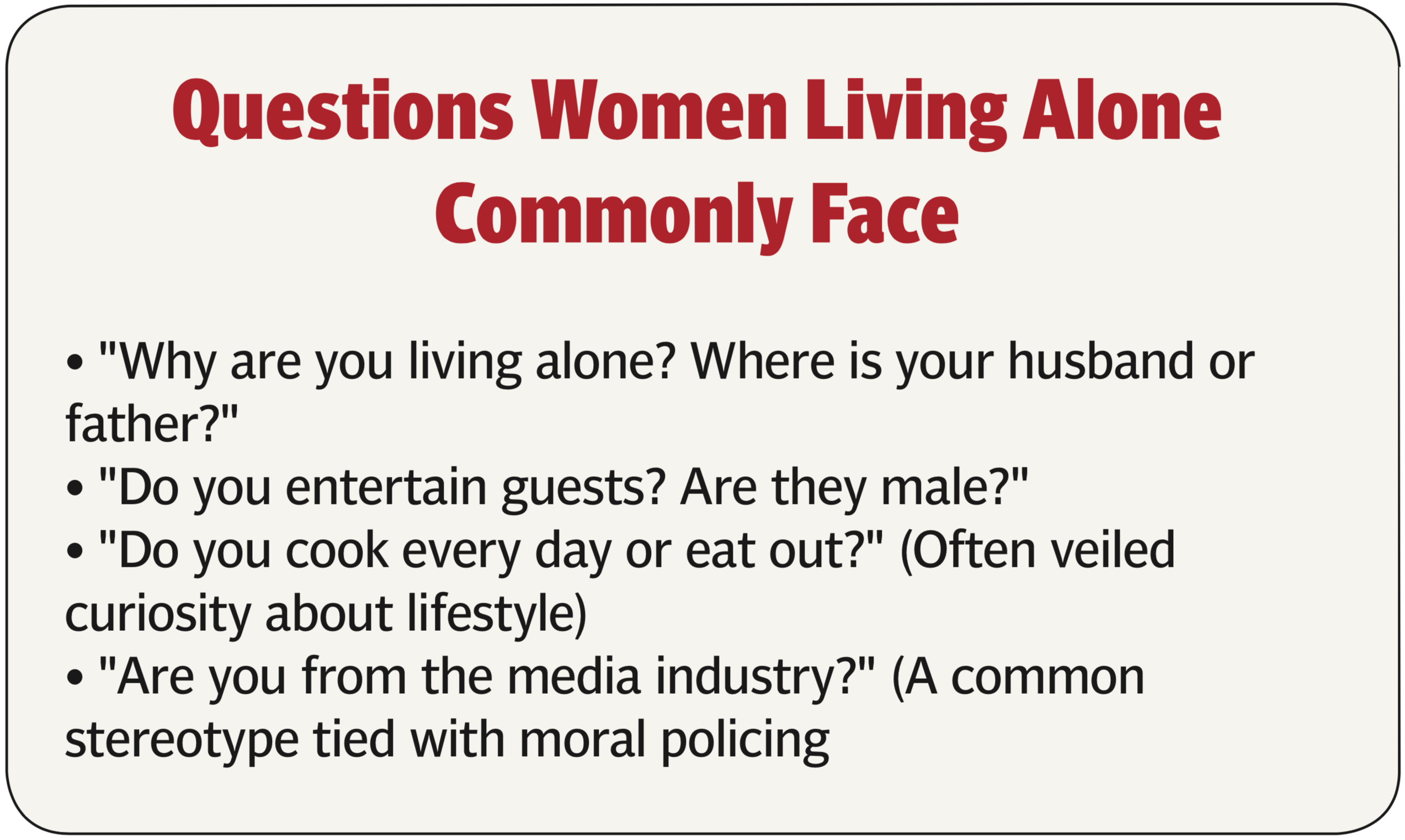

The questions come in quickly, and they are mostly personal such as, “Where is your family?”, “Why aren’t you married?”, “Are you divorced?”, “Do you bring men over?”, “Why do you work late?”, “Are you even respectable?”

These interrogations don’t just come from curious neighbours but often from landlords, security guards, shopkeepers, and sometimes, even coworkers. “My landlord made it a point to ask if I have male visitors,” says Khalid. “He had no such rules for the male tenant living upstairs.”

The constant policing isn’t always verbal. It manifests through silent surveillance CCTV cameras mysteriously pointed toward their apartment doors, unannounced visits by building watchmen, or even neighbours reporting them for suspicious behaviour, which often means coming home late or not dressing appropriately.

“Women mostly don’t interact with people in the building they live in because they get all kinds of judgment. In the building I am living in right now, I don’t talk to anyone. Still, one of the uncles, whose children are also married, tried to be friends with me because, for him, if I live alone, then I am available for casual relationships,” said Laraib Ahmed, who lives in Lahore due to work commitments. She also explained how when she was on a house hunt, an aunty asked her to submit pictures of her father and brother, and also if she had a boyfriend, a picture of him as well, and other than them, no man would be allowed to come and visit her.

The lonely death

In a chilling incident that shook the country, Humaira Asghar, who was found dead in her apartment months after she had passed away. Humaira lived alone and, according to neighbours, “kept to herself.” She didn’t interact much, didn’t share her personal life, and avoided socialising with other tenants, perhaps a survival mechanism in a culture that quickly labels and punishes women for being “too visible.”

Her death raised disturbing questions, Why didn’t anyone check on her sooner? Was her isolation a choice or a necessity? Would her life or death have been any different if society were more accepting of single women?

There was no official foul play reported, but what remained clear was the devastating loneliness many women like Humaira experience when choosing independence.

Harassment under curiosity

The most dangerous repercussion of this scrutiny is the vulnerability to harassment. Men, whether neighbours or strangers, often assume a woman living alone is “available,” or worse, morally lax. This misperception is not just offensive, it’s dangerous.

Women have reported unsolicited advances from neighbours, landlords entering without permission, and stalkers tailing them from work to home. “I had a man in the apartment opposite mine stare at my door for weeks,” shares Shanzay, a university student in Lahore. “One day, he slipped a note under my door asking if I needed company.”

The ordeal doesn’t just end with the house hunt, but managing other things too, such as any maintenance work, is another hassle. “When you live alone for any reason, people such as plumbers or electricians judge your character. If they come, I dress appropriately so they don’t think they have a chance and similarly I was keeping myself very harsh with other tenants specially male bachelors so that they don’t try to be friends,” shares Ahmed.

In 2024, a case in Karachi’s Gulistan-e-Jauhar surfaced on social media where a woman living alone called the police after her landlord barged into her flat, citing a "gas leak emergency" as an excuse. He was later found to have been harassing her for months.

The incident ignited a brief online conversation around women’s safety, but like most digital outrage, it fizzled out without structural reforms.

For women living solo, the home should be a sanctuary. Instead, it becomes a fortress they constantly have to protect. They double-check locks, avoid taking cabs at night, install peephole cameras, and often lie about not living alone, saying a brother or father stays with them to avoid predatory intentions.

Security concerns also influence every aspect of women’s daily routines, such as avoiding ordering food at odd hours, fearing that delivery boys might judge or stalk them later. They hesitate to post anything personal on social media that could hint at their residential status. They avoid friendly conversations with male neighbours, lest it be misconstrued. “I never tell any colleague or even male friend that I live alone, I always tell them that I have a flat-mate,” shared Kiran Butt, who has been living in Islamabad for the last four years. She also pointed out that all of this culminates in a state of hypervigilance where she uses CCTV, does not share addresses, gives false information about flat-mates, and does not go to any colleague’s house as she might have to invite them over next.

Landlords and the housing dilemma

Many single women find it nearly impossible to rent homes or apartments on their own. They are turned down by conservative landlords who don’t want trouble in their buildings. “Every time I called a property agent and said I am unmarried and living alone, they’d hang up or say the flat is not available anymore,” says Sana, a 34-year-old who lives alone in Karachi. “I don’t understand the idea that why do we have to explain anyone that we need an apartment and who will be living with us? Their main concern should be bills and rent paid on time but people have no boundaries and try to intervene in matters that doesn’t concern them, such as why aren’t we married yet, why we are not living with parents or why we are coming to another city to work,” Sana laments.

Even hostels or women’s housing facilities aren’t safe havens. Many enforce outdated moral codes, curfews, visitor bans, or even prayer-monitoring imposing layers of patriarchal control in the name of safety.

The irony is that it is not limited to only single young women but also make women who are single mothers suffer, as in the case of 45-year-old Amber Saba. When she meets landlords along with her 23-year-old son, they ask her all type of questions such as where is her husband, is she a widow or divorced and what were the reasons for her divorce or even to the extent that who will be visiting her if she lives here and how many siblings she has. “I don’t get it, what does the landlady have to do with the number of my siblings,” she says. “Despite my young son, she was adamant to know about my marital problems with my husband.”

Saba, who is a mother of four, isn’t considered a family because her husband has divorced her, and she usually has to pay extra rent for places that are given at lower prices to other families, but just because she is a single mother, many landlords exploit her. “While my divorce case was in the court, my landlady kept on asking all kinds of questions as to why I didn’t reconcile or why the police keeps coming to investigate or why I have not gone to my parents house, to me all these are very personal questions but for her it was like she is being concerned about me as an elder,” Saba shares adding that in our society many people keep crossing boundaries out of concern and for being an elderly figure.

Beyond the logistical and safety challenges lies a psychological war that single women must endure. Living alone in a community-driven culture often isolates them. While male tenants or bachelors are seen as independent or even charming, women are often branded as rebellious, promiscuous, or “westernised.”

Rumours spread fast in residential buildings. A woman returning late from work becomes an subject of gossip. Any male friend or relative visiting her becomes “evidence” of moral laxity. Many women prefer avoiding interactions altogether, like Humaira and Ayesha did, not out of arrogance, but self-preservation.

The psychological toll on women living alone is rarely addressed. Constant surveillance, fear, and judgment can lead to anxiety, depression, and severe loneliness. The lack of emotional support, especially when families disapprove of their decision to live independently, only compounds the problem.

Therapists confirm that a growing number of young, single women reach out for counselling due to issues rooted in societal rejection and constant fear.

What needs to change

There is no singular solution to this multi-layered problem, but there are several ways forward, such as legal protections and housing rights where laws should be implemented (and enforced) to prevent gender-based housing discrimination. Rent agreements should protect tenants specially women, from illegal entry and harassment by landlords. Harassment by neighbours or strangers must be treated with urgency. Reporting mechanisms should be simple, accessible, and effective. Police training on gender sensitivity is crucial. Public awareness campaigns can help dismantle harmful stereotypes about single women. Promoting narratives of successful, independent women can and normalise their choices.

Other than these major aspects, steps that can be done on an individual level such as women-led community groups, can be a lifeline. Whether through safe WhatsApp groups, co-living spaces with vetted security, or mental health circles, having a community to fall back on makes a difference. Also, employers should offer flexibility to reduce commuting risks, especially for night shifts or extended hours. Housing stipends or safe residence options can also be introduced for female employees.

The decision to live alone should be as unremarkable as choosing a career path or selecting a university. Yet, for women in Pakistan, it is treated as an act of rebellion, met not with support, but suspicion.

The broader implications of these safety concerns extend beyond individual discomfort; they affect women’s access to employment, education, mental health, and overall autonomy. When a woman feels unsafe in her own home, harassed by landlords, judged by neighbours, or policed by society, she is being denied one of her most basic rights: the right to exist in peace.

Women often restrict their mobility, limit social interactions, and adapt their behaviour not out of preference, but necessity. This self-censorship is not empowerment it is silent survival. And it reflects how we have collectively failed to make cities livable for half the population.

Policy-level interventions are overdue. There must be legal frameworks that prohibit housing discrimination based on gender or marital status.

Police reforms are equally important. Many women do not report harassment or stalking due to fear of being blamed or not being taken seriously. We need trained, gender-sensitive officers, preferably women-led units, who understand the nuances of safety concerns without moral policing.

At the urban planning level, safety audits of neighbourhoods, improved street lighting, security infrastructure, and women-only complaint desks in residential associations can make a real difference. City governments must collaborate with civil society to create mechanisms for women to report incidents confidentially and access immediate support.

Changing the societal lens

But perhaps the hardest and most crucial transformation must occur in our social attitudes. Living alone is not a moral statement it is a logistical, financial, or personal decision. Media and educational institutions have a powerful role to play in reshaping this narrative. Positive representation of single women in dramas, films, and public campaigns can challenge outdated stereotypes. Community awareness drives in urban neighborhoods can help normalise women's independent living and encourage bystander support in case of harassment.

In a just society, no woman should fear judgment or harm for the simple act of living on her own. Until we ensure her safety and dignity, we are all complicit in reinforcing the walls she must build around herself.

At its core, the issue is not just about living arrangements it is about autonomy. A woman choosing to live alone is asserting that she can navigate life without constant guardianship. For some, it is a necessity; for others, a choice. Either way, society needs to catch up with the fact that women are not vessels of family honour but individuals with full agency.

Until then, every woman living solo is waging a quiet war — a war not just for personal space, but for societal acceptance.

Women living alone in Pakistan today are not anomalies; they are trailblazers. Their solitude isn’t a rebellion; it’s resilience. While society may still view them with suspicion, their presence in urban and even semi-urban landscapes is growing. The need of the hour is not to question why women live alone, but to ask why, in 2025, they still have to justify it.

*Names have been changed to ensure privacy