Meme lords, not warlords: As always, Pakistani memesters are making the most out of India's 'war'

More than humour, our meme game is a refusal of nationalism, nostalgia, and neat endings

At the dinner table, when my family convenes for its routine dispatch of all things political and conspirational, though often it is hard to distinguish one from the other, I do my part by narrating my favourite memes about Pakistan and India's "upcoming" war.

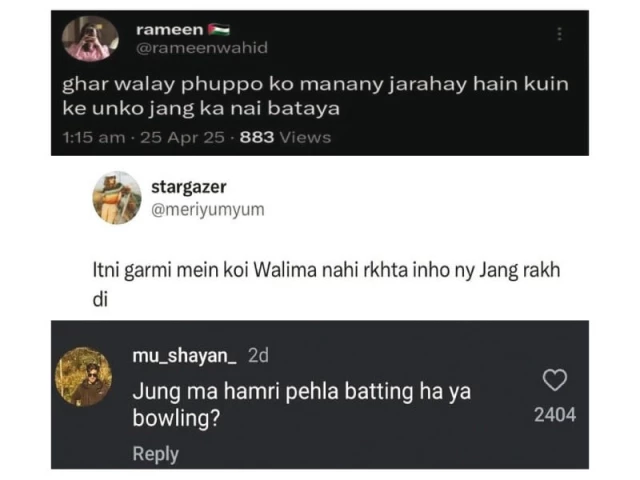

There is one about Sonam Bajwa hosting Jeeto Pakistan, another predicting Salman Khan's marriage at last, broadcast on a local channel's morning show, and one of the most relatable ones, jokes: "Itni garmi mein koi Walima nahi rakhta, inhon ne jang rakh di."

Where once, the mere mention, forget possibility, of a Pak-India war summoned impassioned speculations on Ghazwae Hind, all the nuclear arsenal Pakistan has covertly stocked over the years, and a fragmented recall of Naseem Hijazi, Allama Iqbal, and the two nation theory, it should be puzzling that my family and I, like many others, can find fun at the alleged brink of World War III (or fifth generation warfare, if you will).

"Jinnah literally put all funny people on one side and drew a line." Are Pakistanis really very funny people, unlike India and perhaps the wider global north?

Unbeatable meme game?

As if it weren't already a sentimental flex - you may have everything, but we have a sense of humour - it also, quite whimsically, disowns a nationalist fervour birthed by decades of political and ideological whiplash. Our memes suggest chronically low expectations of the future. "There is absolutely nothing India can threaten us with that we aren't already suffering from at the hands of our government.

You'll cut off our water supply? We already don't get any. You'll kill us? Our government is already doing that. Will you capture Lahore? Thirty minutes in and you'll return it."

Another X/Twitter user puts it more snappily: "Jang kerni ho tau 9 bajey se pehle karlena. 9:15 per gas chali jati hai hamari."

Critics with more sobriety or patriotism may read into this accelerating meme-fication of worsening geopolitical instability as naive, wilfully ignorant, or both. Since when did war become a laughing matter? Even a quick scan of Pakistan and India's recurrent antagonisms will show that the cross-border conflict majorly plays out in rhetoric and discourse. For decades, the entertainment industries have led this front, acting as tranquilisers, softening the sharp edges of intra- and transnational narratives of state-making. At different points in history, it has meant something that a Shah Rukh Khan-starrer, Main Hoon Na, advocated for Project Milaap, or that Meera so easily took to the explicit romance in her Bollywood debut, Nazar (2005). Come 2025, "art has no borders" is nothing but an easy, feel-good truism. Any expectation that Indian or Pakistani actors will usher in sanity is lost between generic platitudes about humanity and unabashed warmongering couched in patriotism.

And maybe that's just as well. The terminally online epoch has conceived new harbingers of sanity - the memesters. At least, on this side of the border.

Anti jingoism

Any discussion of Pakistan's meme game inevitably circles back to 2019, when Muhammad Sarim Akhtar, a comically disappointed cricket fan, became an internet sensation during the Pakistan v Australia match at the World Cup. His expression of frustration quickly transformed him into the globally recognised "angry Pakistani fan" or "disappointed cricket fan."

Earlier that year, on February 27, Pakistan shot down two Indian aircrafts and captured Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman. His now-iconic video, where he praises the "fantastic" tea, sparked a meme that resurfaces annually: Pakistanis wishing Indians a "Happy Fantastic Tea Day," marking the country's swift response to the Balakot airstrike.

These are only two instances when made-in-Pakistan memes travelled past national borders. It would demand a separate, focused piece to trace the history of memes here. Millennials are better equipped to pinpoint the moment when viral "blunders" (Meera trying to pronounce photographer) and low production media artifacts (KitKat talcum powder) collapsed into the intertextual umbrella of internet memes. But the present moment requires neither history nor any one generation's standpoint to understand the Pakistani memester, who is practically the antithesis of a jingoist. Unlike the jingoist, the memester resists genealogy and ownership. And do not be misled by its spelled singularity. A memester is not an individual, but a temporary public, always in flux.

The emerging cyber generations that constitute this public do not bleed green. In fact, they do not bleed at all. Is it because the rotting system we inhabit has bled us dry, and now, there is nothing left to give? Or are we every bit the snowflakes the far right makes us out to be? Perhaps we don't bleed because our generation is all about needle pricks and paper cuts. Nothing goes deeper, beyond the surface.

If a jingoist is always looking back at a golden past, the memester is content with half-formed ideas, quick hits of recognition, and a partial futurity. This is why memes, in Pakistan, as everywhere else, answer less to generations and more to the speed of the internet itself. Of course, everywhere else the memester has become synonymous with brainrot, a hasty coinage that, as per Oxford Dictionary, refers to "the supposed deterioration of a person's mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as the result of overconsumption of material (now particularly online content) considered to be trivial or unchallenging." But not the Pakistani memester. Not at the present moment.

'Not that deep'

The memes coming out right now remember the past: "Ab tau Madam Noor Jehan bhi nahi. Jang hui tau Aima Baig k tarane sunne parein ge." Just as they are aware of common grounds: "Border pe Jhol chala dena, mohabbat jaag jayegi sabki." And they are not forgetting what makes us, us: "Request to the Indian forces: Please leave your valuables in India before going to Lahore," "Ghar wale phuppo ko mananay jarahe hain kyun k unko jang ka nahi bataya."

We are no longer just responding to a fantastic cup of tea or the suspension of the Indus Treaty. We are stepping into a future where the war is already over.

Some may call it "self-trolling" or mistake it for self-deprecation, but it is neither. When every rational response crumbles into a truism, when every sober argument is already dead on arrival, what is left except a meme?

Unlike in other parts of the world, where memes are often seen as a downgrade of public discourse, for us, memes are the discourse - an alternative language built from the rubble of failed conversations and collapsing narratives.

And the Pakistani memester is radical precisely because it is a paradox: belonging nowhere, refusing both nationalism and anti-nationalism, making jokes that could belong to anyone, from anywhere. The longer you scroll, the more you wonder: Is it a Pakistani or an Indian joking that you can cut off water for everyone else, just make sure Hania Aamir gets a glass?

Or maybe you're too busy laughing to care where one ends and the other begins. Because, as the kids say, it's not that deep.

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ