Child labour and a million out-of-school children paint a grim picture in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, while the education scenario in Balochistan merits another story. As Sindh struggles with outdated syllabi, unqualified teachers, and a lack of resources in education colleges, and Punjab faces increasing poverty and population growth — a situation where earning bread take precedence over buying books – these interconnected factors are contributing to the demise of educational standards across Pakistan. What is our future?

The crises in Karachi's colleges

The quality of education in Karachi's public sector education colleges has been steadily deteriorating. Outdated syllabuses, a shortage of qualified teachers, and outdated admissions policies are key factors behind the decline, especially in education-related subjects and the Bachelor of Education (BEd) program. This situation is alarming, as these colleges are responsible for training future primary and secondary school teachers. The dropout rate is also on the rise, making the problem worse.

Several years ago, Sindh's education department was split into two separate divisions, but the transition has been far from smooth. The college education department, which now manages colleges, has largely remained focused on administrative tasks such as transfers, postings, and budgets, rather than addressing the academic concerns plaguing these institutions.

Professor Zakaullah confirmed these challenges when contacted by The Express Tribune. "During my time as principal, I identified numerous academic issues," he shares. "One of the most pressing being the shortage of core subject teachers. In my own college, only three teachers were qualified to teach education-related subjects, while the rest were general subject teachers."

He further highlighted another significant issue. "We are training students to become teachers, but the trainers themselves often lack practical teaching experience," Zakullah points out. "Many of them have never taught in schools and may not be fully aware of effective teaching methodologies."

The dropout rate for BEd students is alarmingly high, with an estimated 50 per cent of students failing to complete their degrees. This is particularly concerning given the high number of female students enrolled in the programme. Various factors contribute to this dropout rate, including academic challenges, financial difficulties, and personal commitments.

There are actually two ways to become a teacher through these colleges. One option is a four-year programme open to students who've just finished high school (intermediate). The other is a two-and-a-half-year programme for those who already have a two-year degree like a BCom, BA, or BSc. This way, people with different backgrounds can all get the training they need to become educators.

"After the admissions for Karachi University and other universities are complete, students who miss out often turn to Jamia Millia," explains Professor Zakaullah. "Many of them come to these colleges out of necessity, seeking a degree to boost their credentials. However, a significant number of them eventually drop out, indicating a lack of genuine interest in pursuing education."

He further revealed that the syllabus hasn't been updated since 2012, leading to outdated curriculum. Many subjects are no longer relevant and should be replaced with more current topics. Despite submitting a report on this issue to Sadaf Sheikh, the former secretary of college education, who has now been transferred, there's uncertainty about whether the new secretary is aware of these problems.”

Despite these challenges, Zahid Rajpar, acting director of colleges in Sindh remains hopeful. "Steps are being taken to rationalise the number of teachers and upgrade education colleges to academy status, which could improve the quality of teacher training and better prepare graduates for classroom teaching. However, the confusion surrounding BEd programme titles—where the four-year programme is called "Elementary" and the two-and-a-half-year programme is called "Secondary"— adds more complications.

“The situation in our college is not too dire, but there are some challenges in academics and core subjects,” shares Professor Naveed Rab, Principal of Government Education College, Federal B Area in Karachi. "There is a clear shortage of teachers, and it would be more effective if BEd programmes were taught by instructors who themselves have a BEd degree."

"The transition to the semester system has led to increased discouragement among students who fail papers and are forced to repeat the year,” adds Prof Rab, who has recently been appointed as the director general of colleges, Sindh. “This has contributed to a higher dropout rate in both the four-year and two-and-a-half-year BEd programmes."

Bread or books?

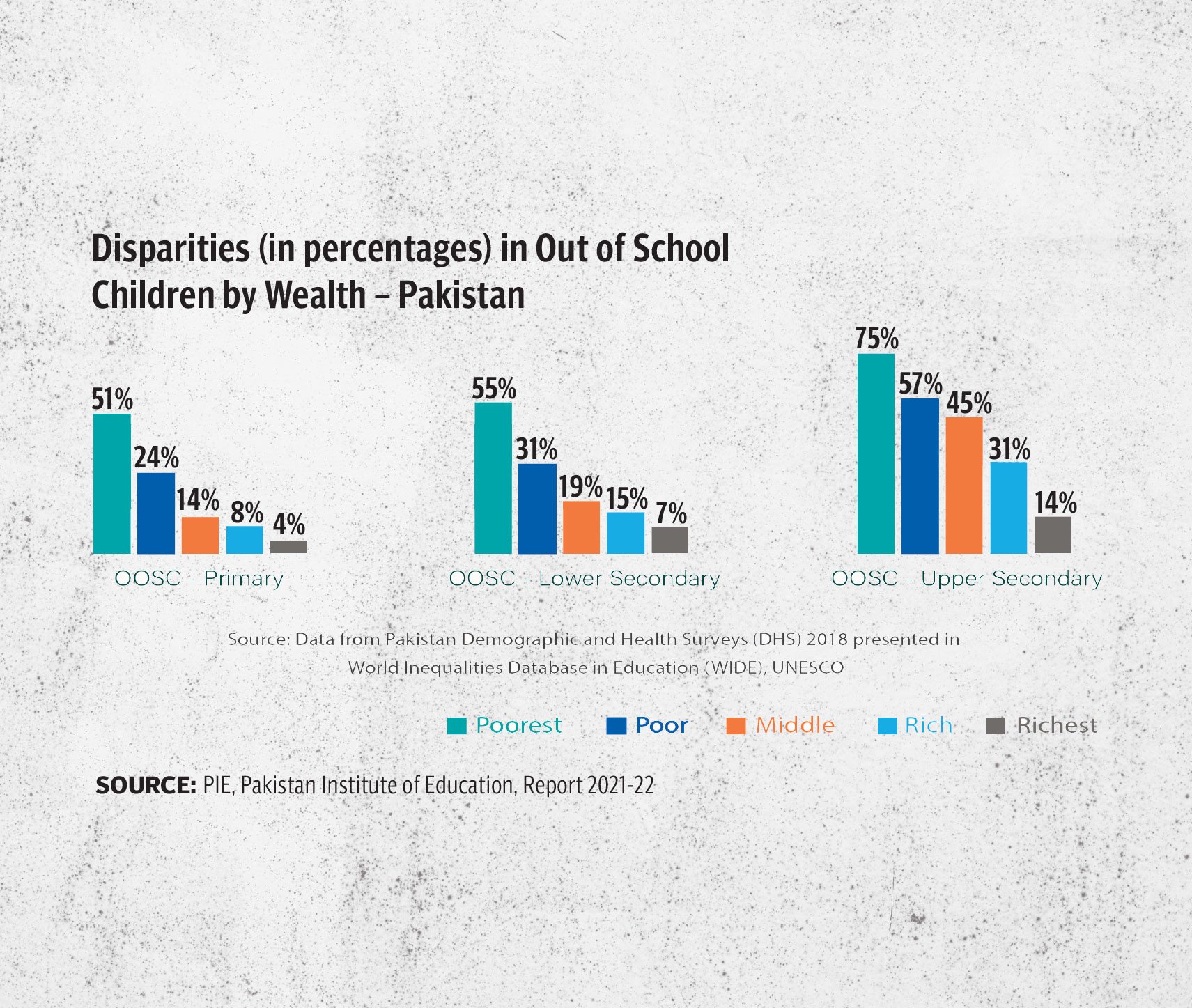

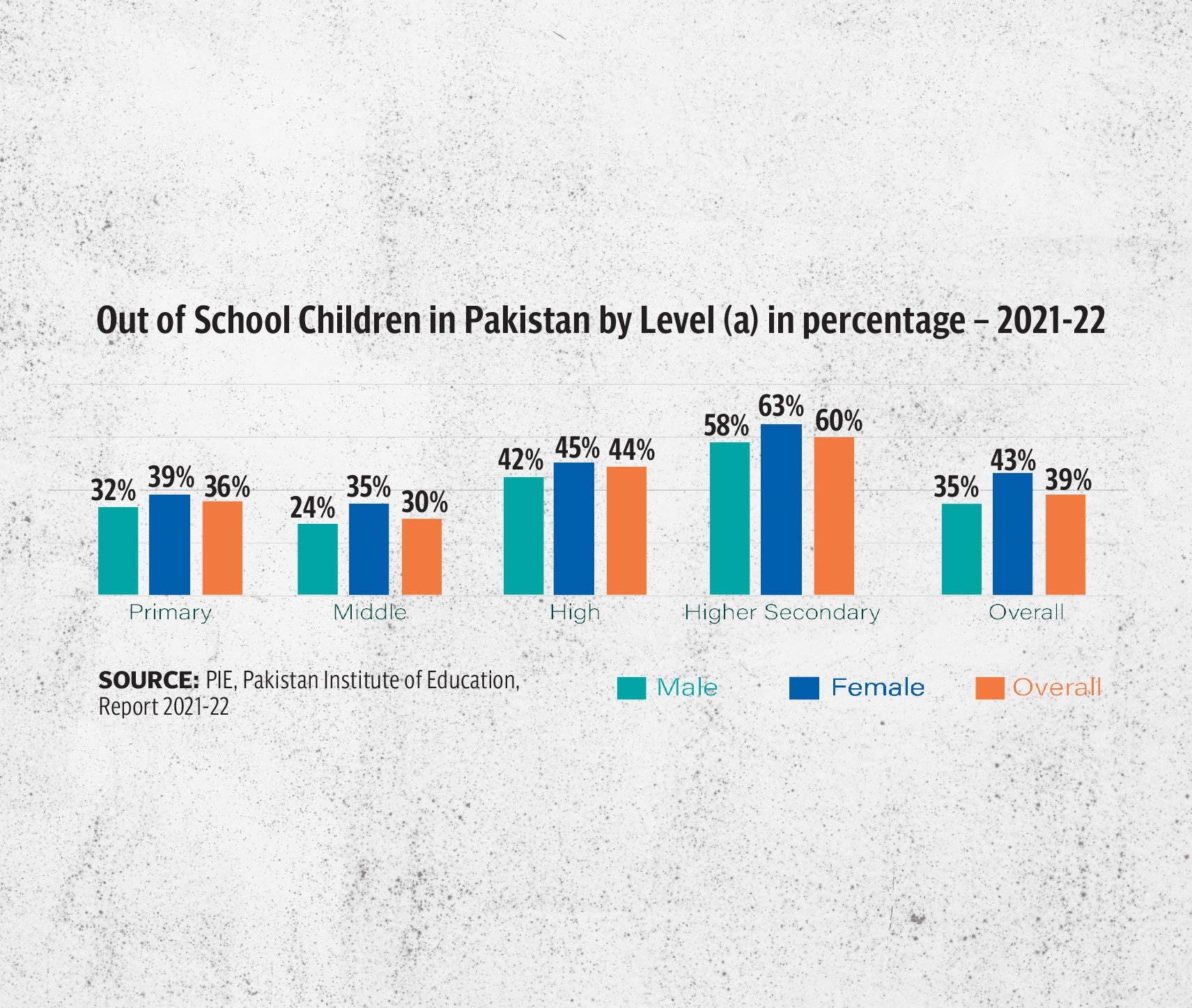

Karachi's education crisis is not isolated. A recent study reveals that Punjab also faces an alarming dropout rate, with 60 per cent of students leaving school before completing intermediate classes. In rural areas, where poverty is more widespread, the issue is even more acute. Official data shows that the dropout rate in Punjab is highest at the primary level, particularly in rural areas. While 10.4 million children are enrolled in schools across the province, only 7 million complete primary school. This number further declines to a mere 1.2-1.3 million by grade 9.

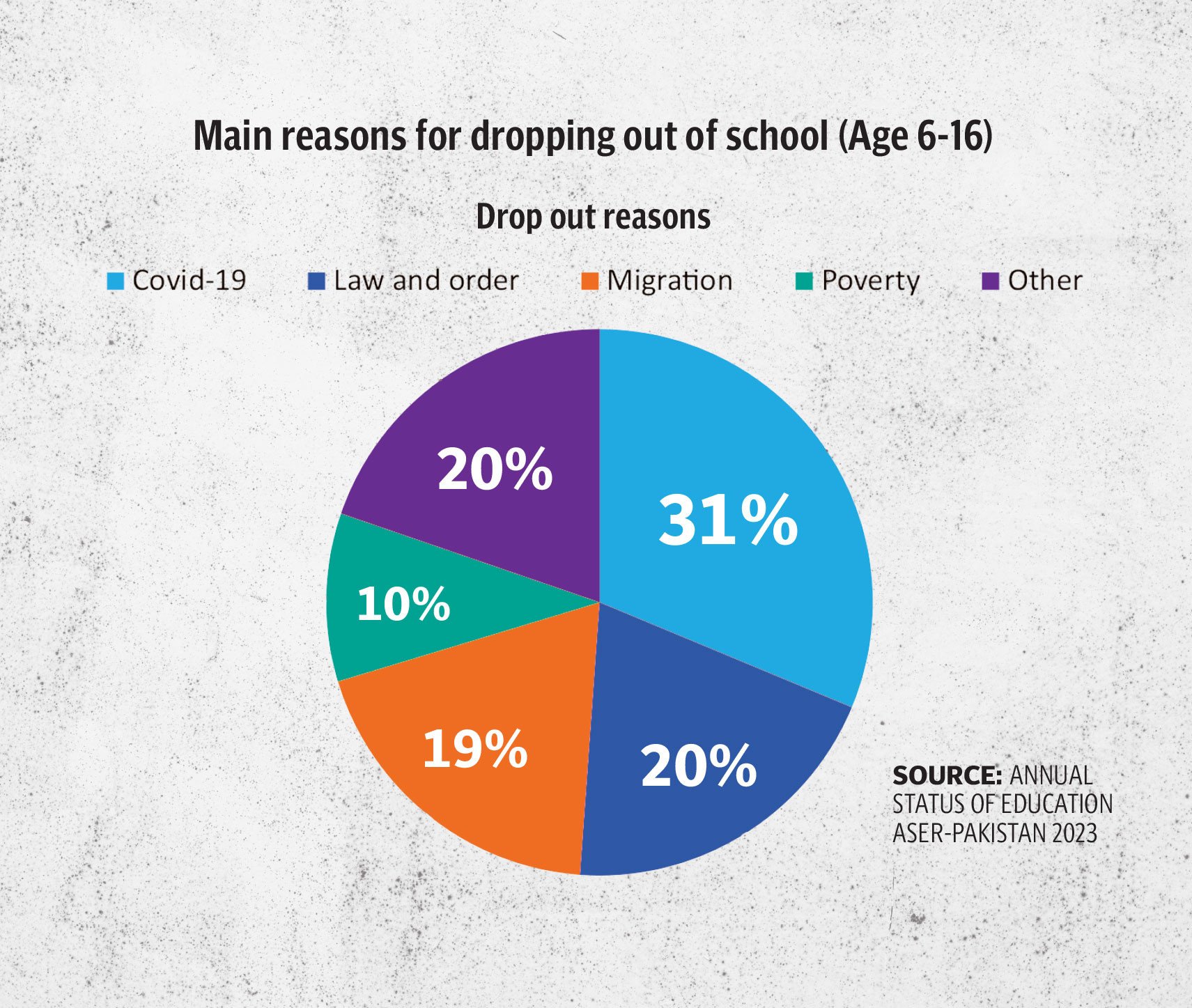

Education experts attribute the high dropout rate not to the education system, but poverty. Parents force children to work to support household expenses. Additionally, increasing costs of books and stationery only aggravate the issue.

According to Rana Liaquat Ali, an education expert, teachers have implemented government-recommended reforms and provided facilities for students. However, he emphasises the difficulty lies in in convincing parents, many of whom are illiterate, to support their children's education.

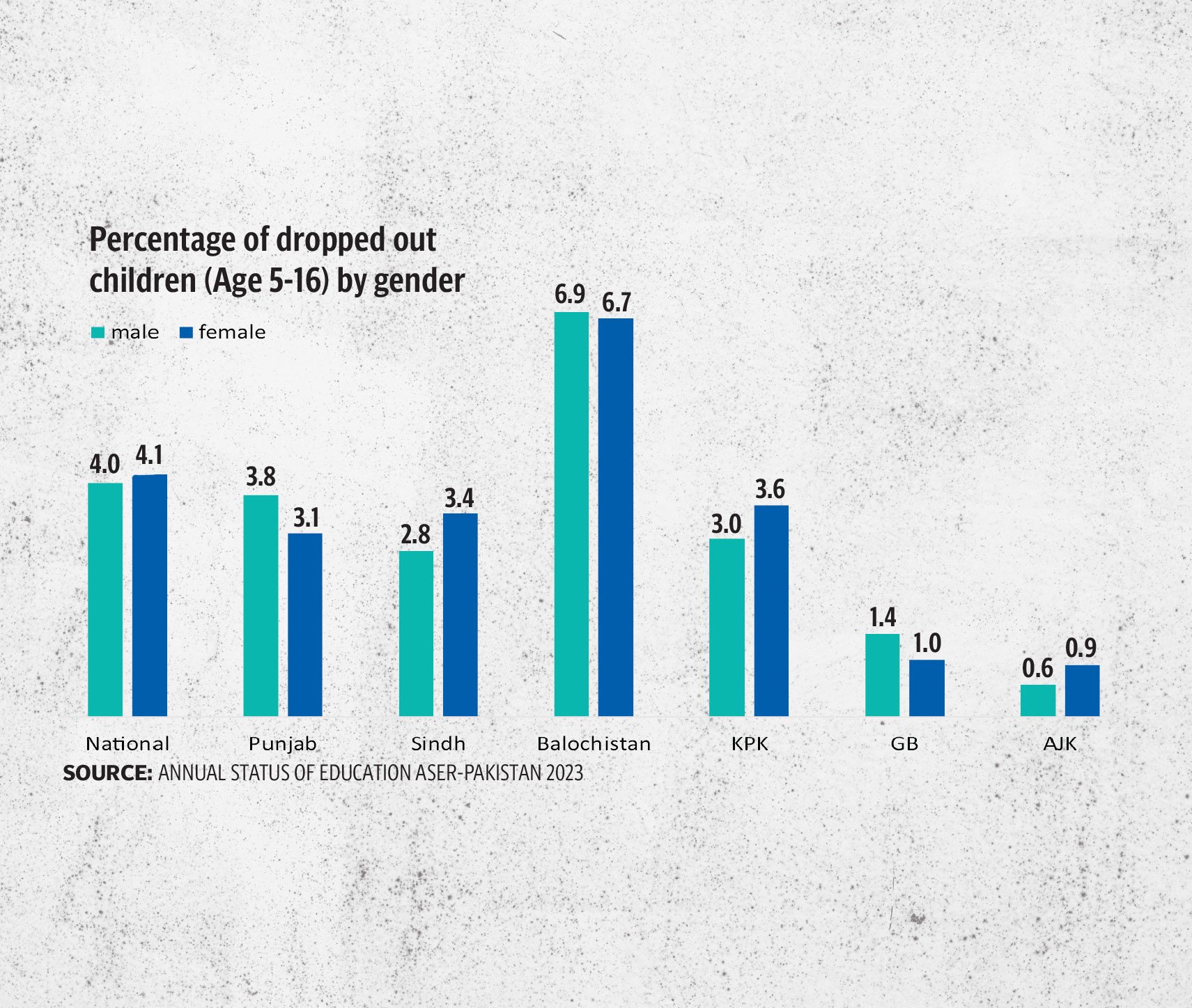

"Many parents prioritise earning money over education, believing that their children can earn more by working than by attending school," says Ali. "This mindset contributes to the alarming dropout rate of 5 to 6 million students annually. The government must provide relief from inflation and offer subsidies to parents to encourage them to send their children to school. Teachers are working on reforms, but convincing parents, especially those who are illiterate, remains a significant challenge.”

A recent survey of teachers revealed that all children aged 7-13 want to attend school. However, domestic constraints and parental reluctance often prevents them from doing so. Uneducated parents prioritise basic necessities over education, expressing the sentiment, "We worry more about bread than books."

The Education Department reported a 100 per cent enrollment rate for classes 1-3, which drops to 40 per cent by grade 8, and 80 per cent by university level. Economists like Dr Qiyas Aslam attribute this trend to Punjab's large population, high poverty rate, and low purchasing power.

He stressed that increasing the literacy rate, currently at 60 per cent, is crucial for Punjab's development. “The government must ensure easy access to education, making it affordable for families,” says Aslam.

With 14 million children entering schools annually, experts warn that the dropout rate will persist unless addressed. The government must prioritise education subsidies and relief measures to break the cycle of poverty and ignorance.

Punjab has 47,400 schools, offering education from grade 1 to intermediate, in addition to 7,000 schools under the Punjab Education Foundation (PEF). The province allocates over Rs450 billion for education, with Rs360 billion for teacher salaries, and the remainder for non-development funds.

Currently, Punjab has 310,000 teachers, with a shortage of approximately 125,000. These 125,000 vacant positions of teachers have not been filled for the past many years. Over 15,000 schools lack teachers, with some having just one teacher. The government is working to address this issue by hiring temporary teachers and conducting recruitment drives.

Muhammad Ejaz, a parent from Lahore, shared that his child had to drop out of school to support the family financially. "My child was in 5th grade, but he now works with us to support his four siblings,” he shares.

Muhammad Azoor, a teacher, suggests that the government must provide subsidies to parents and collaborate with local representatives to increase school enrollment, while 10-year-old Noman, who dropped out of school, wants to continue his education, but has to work to support his family. "I want to study, but we can't afford school, so I have to sell items on the streets to make ends meet."

“To address the out-of-school children challenge and reduce dropout rates, schools have introduced double and triple shifts,” stated Rana Sikandar Haider, provincial education minister, Punjab. “This allows children who cannot attend morning shifts to join second or third shifts."

With 14 million children entering schools annually in Punjab, the province struggles with a teacher shortage. The education system has 310,000 teachers but requires 125,000 more to meet demand. The government is trying to fill these gaps by hiring temporary staff and conducting recruitment drives, but the problem persists.

KP’s children without a future

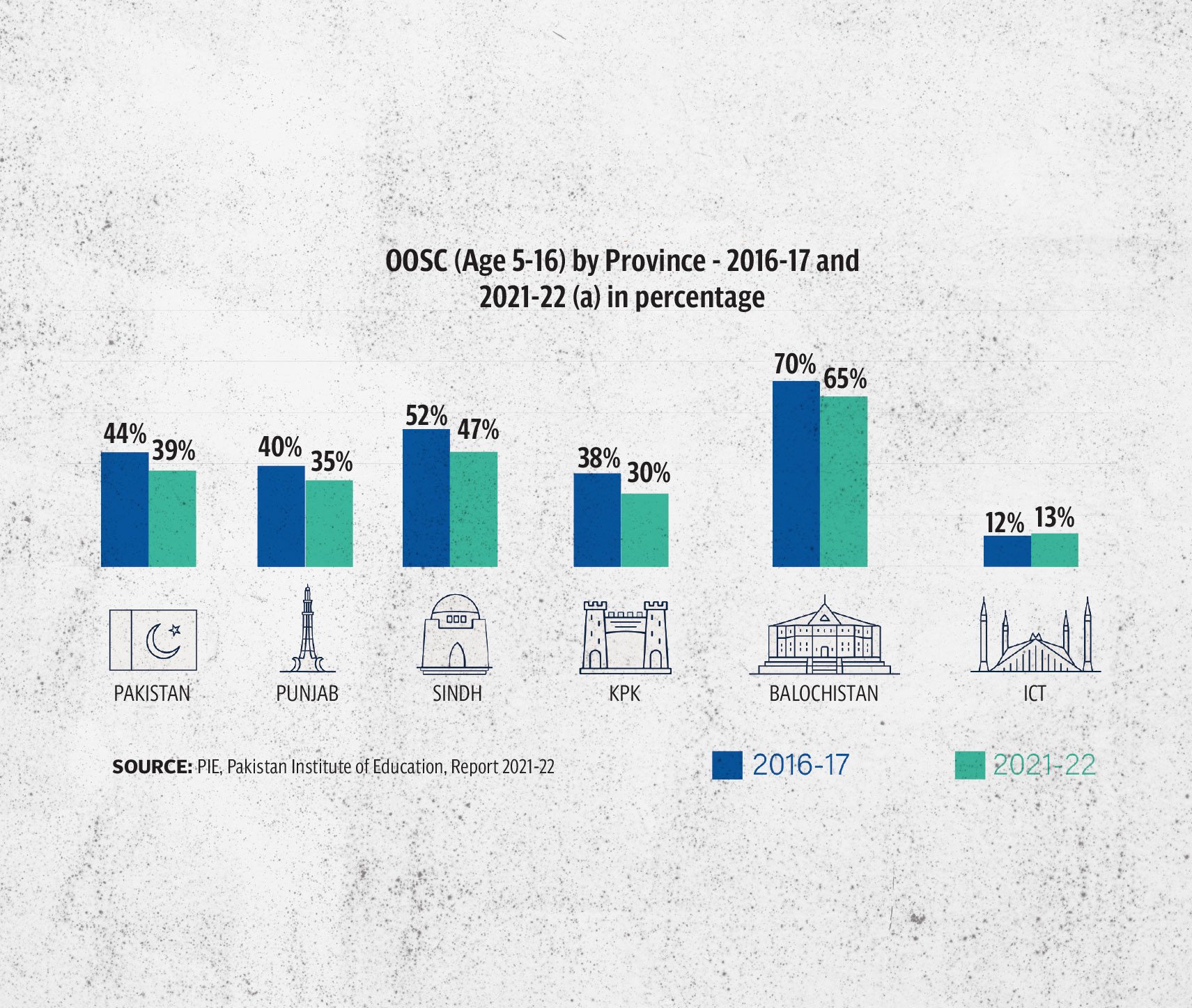

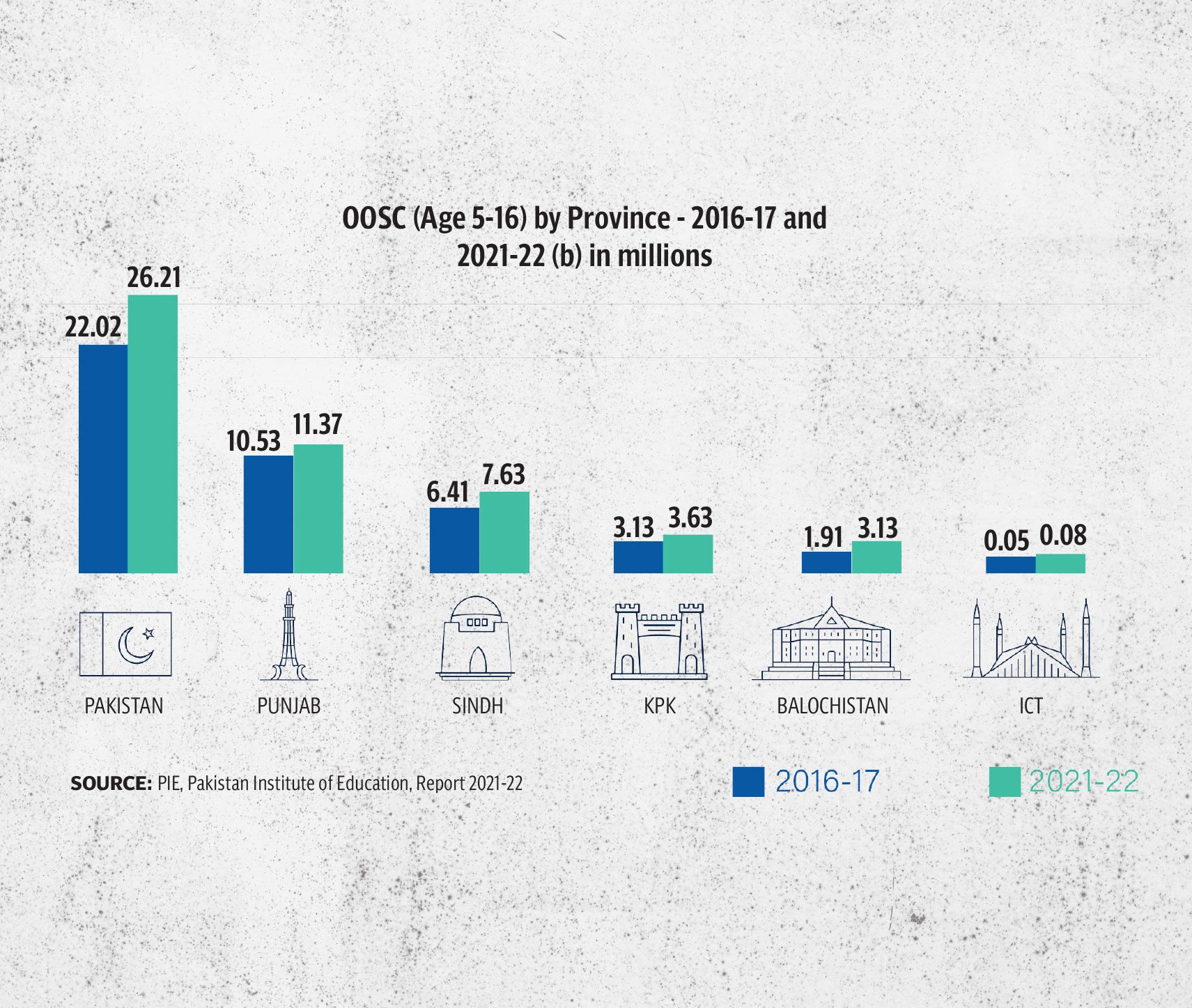

Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa is also facing a severe education crisis, with millions of children out of school. The Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) 2021 report revealed that 4.7 million children aged 5 to 16 in KP are not receiving an education. Of these, a staggering 2.9 million are girls. In areas like North and South Waziristan, as well as other merged districts, the situation is particularly dire, with up to 70 per cent of children not attending school. Gender inequality is a major factor, with 74.4 per cent of girls being deprived of education, compared to 38.5 per cent of boys.

Child labour is another significant barrier to education in KP. The Child Labour Department Survey 2022-23 found that 19,000 children in KP are working in agriculture and other sectors instead of attending school. This perpetuates a cycle of poverty, where children’s immediate financial contributions take precedence over long-term educational aspirations.

According to child rights activist Imran Takkar, education remains a distant dream for many children in KP. He stresses the need for increased budgetary allocations, improved infrastructure, and a cultural shift in the province. Families need to view education as a basic right rather than a privilege. In merged districts like Khyber, Pakistan Alliance for Maths and Science (PAMS) reports that 51 per cent of children are out of school, with Bara and Mulla Gori showing even higher rates of out-of-school children at 54 per cent and 61 per cent, respectively.

In these areas, a staggering 79 per cent of children have never attended school, while 21 per cent dropped out after enrolling. Peshawar, the provincial capital, is also facing a severe crisis, with 519,928 children out of school, representing 35 per cent of the school-age population. Female literacy rates in many tehsils are abysmally low, with areas like North Waziristan and Bajaur showing literacy rates below 5 per cent.

In 18 tehsils across KP, female literacy rates are below 10 per cent, further highlighting the gender disparity in education.

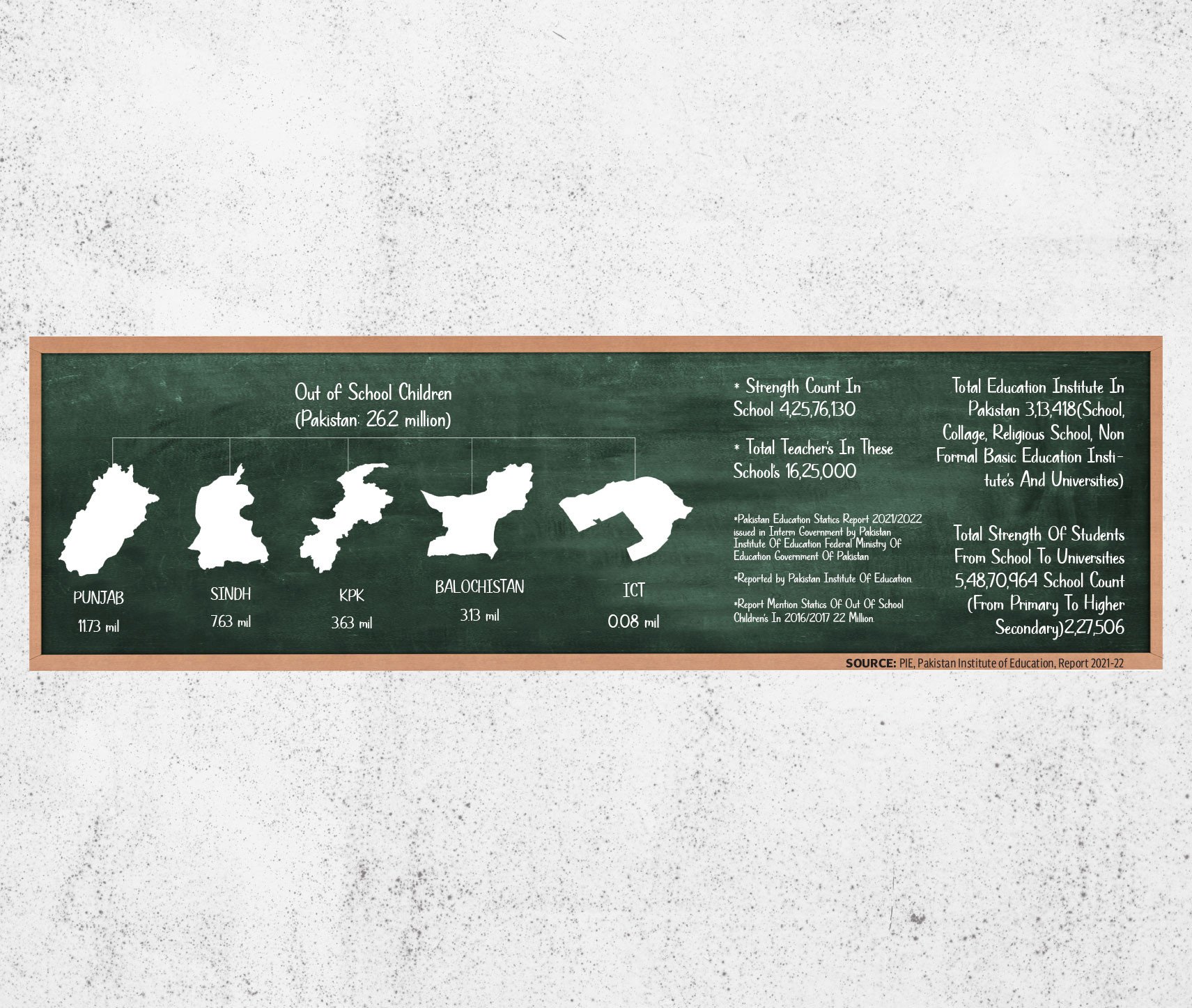

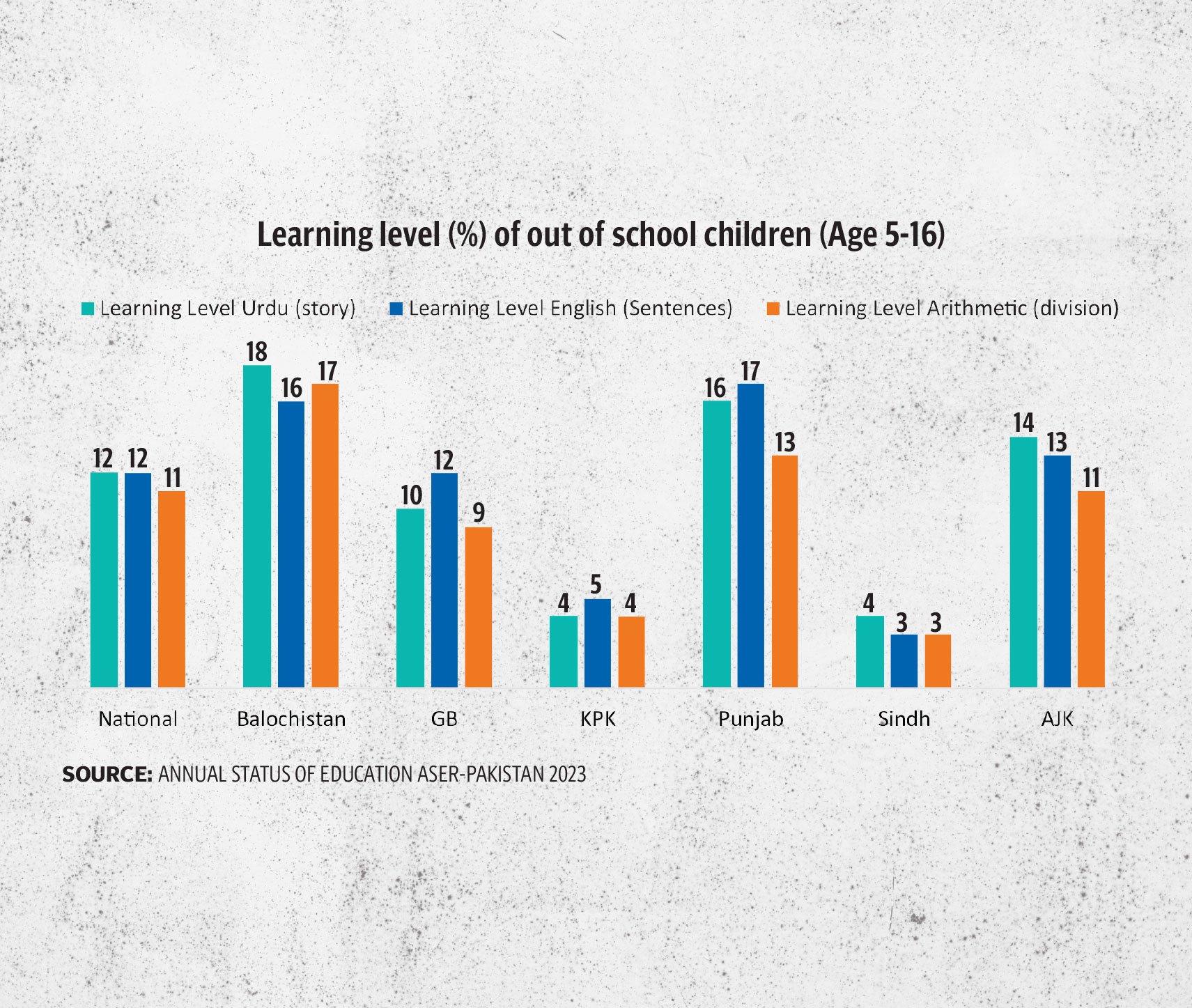

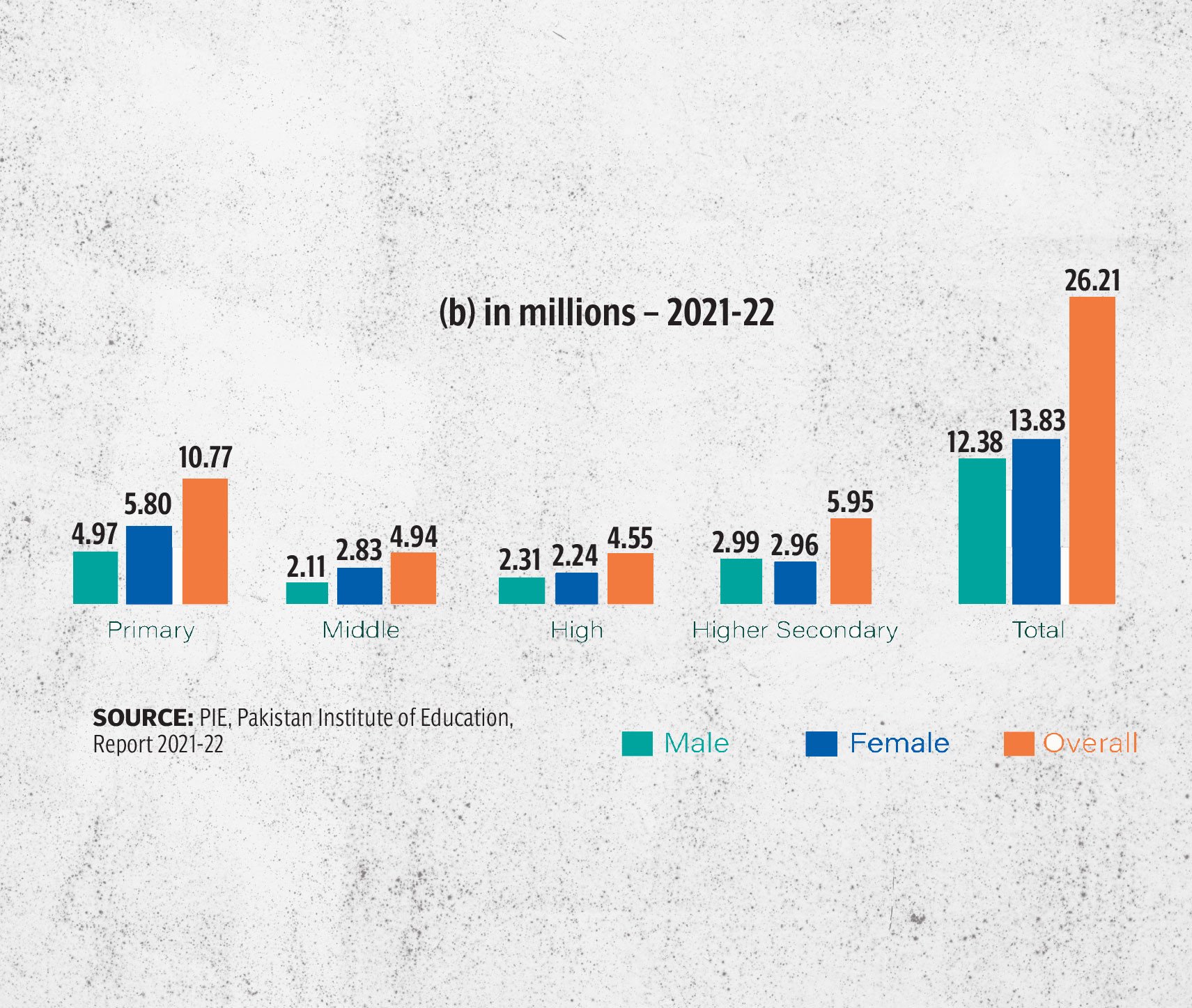

Umer Orakzai from PAMS notes that according to the 2023 census, there are 71 million children between the ages of 5 and 16 across the country, representing 30 per cent of the total population. Of these, 25.6 million are out of school, with 79 per cent having never attended school. He stresses the need for urgent reforms, pointing out that although KP has made strides in governance and management, the quality of education remains lacking.

Faisal Khan Tarkai, KP's minister for elementary and secondary education acknowledges the challenges but remains optimistic. He reveals that 1.2 million children have been enrolled as part of the provincial admission campaign, with plans to admit another 300,000 in the next phase. To accommodate more students, the government has introduced double shifts in schools and rented additional buildings. However, Tarkai admits that the rapidly growing population continues to strain the education system.

The right to education is enshrined in Pakistan's Constitution, but our education crisis is a blatant violation of Article 25-A, a fundamental right that guarantees free and compulsory education for all children aged 5 to 16. It's time for our policymakers to take decisive action to address this crisis and ensure that every child in Pakistan has access to quality education.