The casual reader scanning through the country’s written constitution might be satisfied upon reading the list of fundamental rights guaranteed to all citizens regardless of religion, gender, caste or ability. But the reality for people with dwarfism is a bit harsh.

While all forms of discrimination against the subordinated segments of society are a common occurrence across our society, differently-abled people such as those suffering from a physical impairment known as dwarfism have to confront the worst form of marginalization, since apart from their diminutive representation in the socio-political sphere and their negligible participation in employment and education, the community also has to keep up with the continuous challenge of surviving in an urban landscape that is structurally incompatible with their accessibility needs. In addition, they also endure the consistent displays of dismissive mockery from everyone around them.

“People with short stature are often unjustly ridiculed in our society,” says Zardad Bulbul, a renowned actor and member and activist of the dwarf community. “When we leave our homes, both grown-ups and children smirk at us while others mock us with offensive names. Neither society nor the government is willing to accept us. Although NADRA has declared us as special persons there is no special quota in any government department for our jobs. Even when some dwarf people are able to pave a path for themselves across different sectors such as education, health, and even national service, they are not given the respect and dignity that is afforded to other people.”

“People with short stature have their own dreams yet these are limited by discrimination towards their height,” adds Syeda Imtiaz Fatima, an activist working for the rights of differently-abled people.

What is dwarfism?

According to the clevelandclinic.org dwarfism, also known as skeletal dysplasia, is an umbrella medical term that includes hundreds of conditions that affect the growth of bone and cartilage, resulting in adult stature below four feet ten inches.

“The most common cause of dwarfism is a disorder called achondroplasia, which causes disproportionately short stature,” explains Dr Muhammad Hussain, President of the Pakistan Paediatric Association’s K-P Chapter. “This disorder usually results in an average-size torso and short limbs, with particularly short upper arms and upper legs.”

Diving into the causes of dwarfism, Dr Faryal Tariq, an endocrinologist, highlights the fact that malnutrition during pregnancy is a leading factor of stunted growth in children, which often causes dwarfism.

“In addition to malnutrition, a deficiency of the growth hormone (GH), Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) and Thyroxine (T4) can also contribute to the condition,” adds Professor Dr Zaman Shaikh, a hormone therapy specialist at the Sir Syed Medical College. “A physical examination, blood test and X-ray are used to diagnose the condition, which can be treated with growth hormone therapy.”

The dearth of census data

According to Dr Faisal Bari, an expert on disability inclusion and Associate Professor of Education and Economics at the Lahore University of Management Sciences, there is a dearth of data on the dwarf community in Pakistan. “First off, an adequate number of relevant questions on disability are not put out in large scale surveys across Pakistan,” he shares. “The census only has one question on disability hence the numbers are very low. Normally, each population has 10 to 12 per cent of people with disabilities but the census numbers in Pakistan show a percentage even less than one per cent for a population of 240 million. Secondly, when there is no data then policy making itself becomes difficult because we don’t know the exact numbers of the subcategories of differently-abled people. Hence, systematic research and good descriptive work is missing on people with disabilities and the little work that exists is scattered and can be found occasionally in newspapers.”

Confronting discrimination

For a society where people with dwarfism are either customarily recruited by fancy hotels as an amusing spectacle seated outside the entrance or exploited by TV shows as extra characters in their comedy scripts, the dwarf community’s struggle for their fair share of representation in the public sphere remains an on-going tussle.

Sahar Saeed, 36, stands proudly at 3 feet 5 inches tall. “Firstly, people with short stature are often afraid to leave their homes for seeking employment since they constantly fear getting ridiculed,” she shares, narrating the infelicitous obstacles that she had to overcome before she could land a proper job at the digital department of a private TV channel. “Even if they are compelled to go out, most of the times they cannot find ordinary jobs. The same issues are confronted when they want to go out for education.”

Concurring with Sahar, Muhammad Ramzan, another dwarf with a height of 4 feet 5 inches, shared his tough academic journey through school before he finally decided to drop out.

“When I was in school, my peers used to mock me by calling me "kodu" [a derogatory term for short people] and "bona" [meaning dwarf],” recounts Ramzan. “They wouldn't let me play cricket or football with them and I had to suppress my eagerness to engage in school activities. After facing numerous difficulties up until matriculation, I realised I no longer had the courage to continue my education amidst such derisive circumstances.”

Dr Bari asserts that people with dwarfism should have access to education and employment the same way as other people.

“There are very few jobs in which height is a requirement,” he says. “Unfortunately, the main issue lies in the inveterate mind-sets of people in our society, who are unable to view height differences through an eye of inclusion hence they belittle people with short stature. Under this culture of discrimination, the lens through which we view the world amplifies differences to the point where a differently-abled person’s survival in society becomes impossible and their access to opportunities is unrightfully restricted. This can be addressed through policymaking and legislation, so that people are ensured access to education and employment as a matter of right.”

Dr Uzma Ashiq Khan, Professor of Gender Studies at the Lahore College for Women University (LCWU) believes that the plight of discrimination was significantly amplified in case of women with a disability. “Even women who are not differently-abled struggle continuously to excel in their professional lives since they are stuck in an endless battle with opposing social forces, which seek to undermine their efforts,” she says. “In such a scenario, when a woman is living with dwarfism, the struggle for acceptance is even more. As a society, we still follow superficial criteria for marriageability of women, and obsess over innate characteristics such as height and skin tone. Therefore, success in the marriage market is also typically a challenge.”

Navigating a giant world

For a regular person going through their day which may entail opening a closed door or withdrawing cash from an ATM would require minimal effort since the ease and frequency of performing the tasks allows them to be integrated into the body’s reflexes. Yet the same mundane tasks demand an insurmountable amount of effort from a person with dwarfism since both the doorknob and the ATM keypad are almost always out of arm’s reach.

“Apart from the social prejudices that plague our existence, the lack of accessible infrastructure and facilities at public places also acts as a major hindrance in our inclusion,” points out Sahar. “For instance, the ticket counters at bus stations are constructed at a height which is inaccessible for us. Similarly, at NADRA offices, there are no special, accessible counters for people with dwarfism. During the elections also, stamping the ballot papers is a major challenge since the ballot box and papers are positioned at higher places.”

If the world around you has been designed for a certain, mainstream height, then each and every task would be a challenge for people who fall below that fixed height. “Whether it’s getting on a bus, grabbing a doorknob or lock, reaching a shelf or accessing a toilet, the lack of accessible infrastructure creates a host of problems for people with dwarfism,” explains Dr Bari. “Urban spaces must incorporate infrastructure which assists people with dwarfism in going about their day. People may argue that dwarves are far and few so why offer separate facilities for them, but this is a global concept. Most countries around the world prioritise disability inclusion, which implies that all people regardless of their physical or cognitive differences are able to access the same facilities in the same manner as a matter of right. So, the same concept must be incorporated into the design of all our cities and public and private institutions.”

Dr Bari’s assessment holds value considering the fact that Pakistan too is a signatory of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), under which it is the duty of the state to respect, protect and fulfil human rights. As per the rulings of the United Nations, the obligation to fulfil means that a state must take positive action to facilitate the enjoyment of basic human rights, which in this case naturally implies that it must comprehensively invest in all those infrastructural modifications, at the level of institutions and cities, that are necessary for a person with dwarfism to go about their day and live a regular life.

Disability inclusion

Disability inclusion through accessible infrastructure should be a part and parcel of the way we think about designing urban spaces; it should not be an afterthought. “Furthermore, the culture of discrimination must be addressed through the media by producing TV plays, advertisements or books which feature people with dwarfism,” points out Dr Bari. “In fact, there is very little illustrative representation of differently-abled persons in our school textbooks even.”

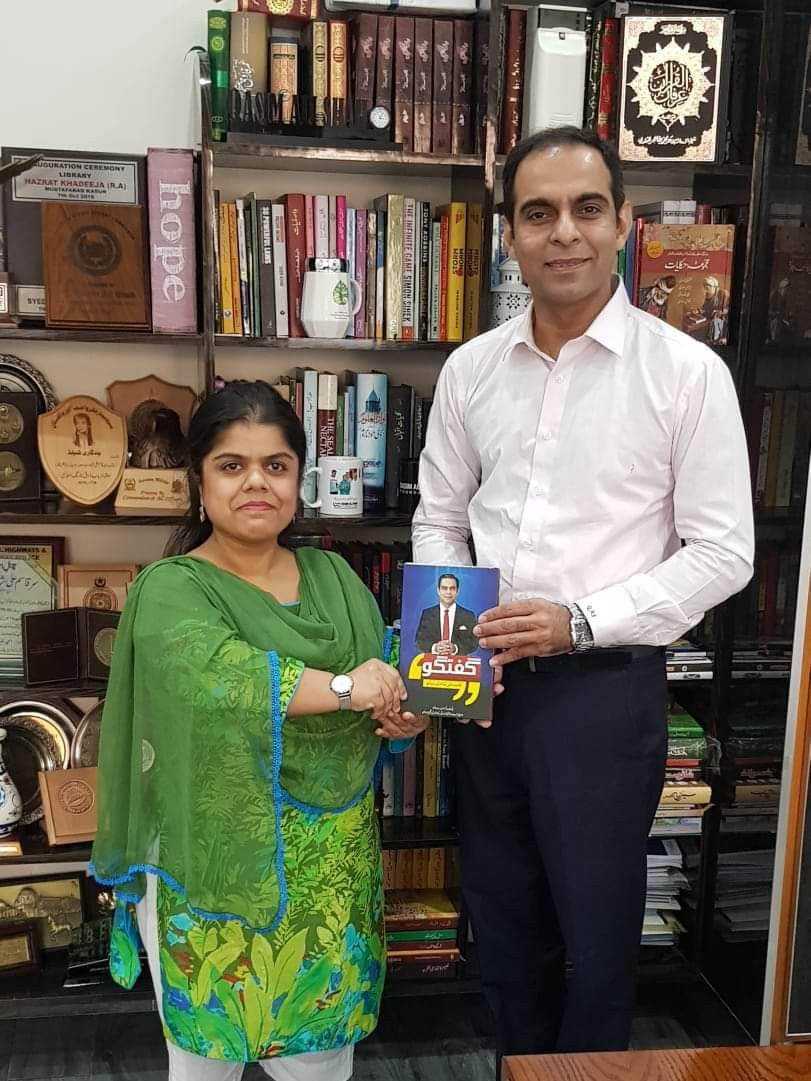

Bulbul agrees with Dr Bari’s views on the need for representing little people in popular culture and the sluggish progress of disability inclusion in Pakistan’s showbiz.

“In the West, dwarf actors like Peter Dinklage, are given roles in hugely popular shows like Game of Thrones,” he says. “Sadly, very few opportunities are given to the dwarf people in Pakistan showbiz industry.”

Only changing the mindsets and normalising differences can bring about real change. “All citizens, especially public figures like intellectuals, policy makers and media practitioners have a role and responsibility to endorse inclusion not just as a matter of courtesy but of civil duty,” sums up Dr Bari. “Each one of us must contribute to create a society where disability inclusion is the basic principle of living.”