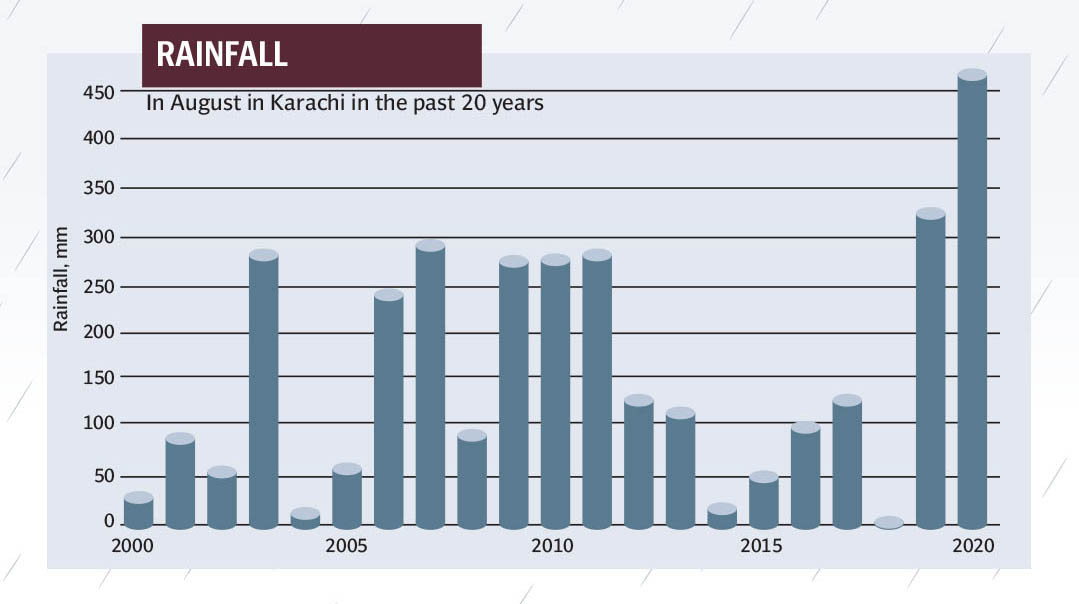

Rain and infrastructure are major issues for Karachi, the largest metropolis in Pakistan and among the world's most populated urban areas. The city's rapid population increase and poor infrastructure development make rainstorm events more damaging. The recent rains have put a question mark on many aspects of the city administration. If Karachi was unable to sustain even an hour long downpour then what can be expected when the monsoon season hits later in the year?

The severe floods that Karachi has seen in recent years during the monsoon season have brought attention to the urgent need for infrastructure improvements to lessen the consequences of heavy rains. Every year, many urban development projects are introduced to counter the flooding in the city, and millions of rupees are invested in investigating the connection between rain and Karachi's infrastructure to help suggest some possible fixes.

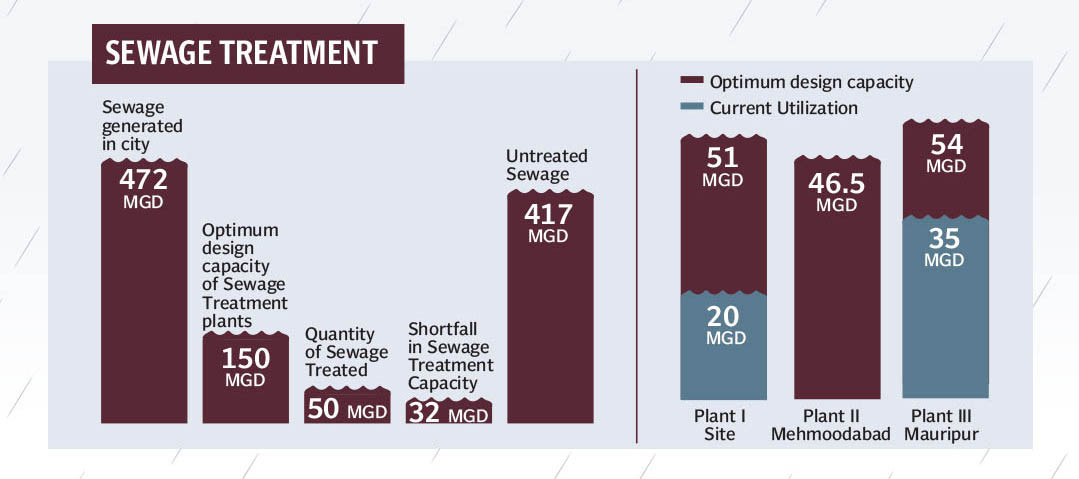

Karachi's infrastructure is inadequate to withstand prolonged periods of rain which results in significant flooding and disruption of routine life. The city's antiquated drainage system cannot handle the amount of water that the monsoon rains bring. The issue has been exacerbated by the intrusion of natural drainage systems brought about by the rapid urbanisation of the area. “There is no drainage system in the city, no one ever invested in a drainage system in the city,” said urban planner Farhan Anwar. “The lines of sewage and nullahs have been used as drainage in the city which is why the system collapses during every rainfall.” Drainage problems are made worse by improper solid waste management since clogged drains make floods worse.

Anwar explained that currently Karachi does not have any drainage system in place and uses sewage lines for rainwater drainage. “Natural basins of drainage such as the Malir and Lyari streams are heavily compromised. The reason being that either they are encroached by the poor and the homeless or by commercial construction, so where will the water go? It will come out on the roads and then into homes,” he said, adding that besides construction on these streams, garbage is dumped in the rain streams. Yet, no one bats an eye on this issue. It is only a few weeks prior to the monsoon when an ad-hoc system to clean the nullahs.

Nullahs or seasonal streams, rivers, and wetlands are examples of natural drainage routes that are being encroached upon due to rapid urbanisation and unrestrained expansion. These incursions interfere with the water's natural flow and diminish drainage systems' ability to control precipitation runoff. “The main reason for such flooding on drains is they do not make culverts on the pathways of water. Across the city, culverts are not made properly, which is why the flow of water gets disturbed. In many cases where they are made, out of six, three are clogged, which disturbs the water flow,” explained urban planner Mohammad Toheed. The Karachi Water and Sewerage Corporation, responsible for sewage drains, connected the drainage system to storm water drains so now all the water, whether rainwater or wastage, flows from the same drains and that adds to the flow, he added.

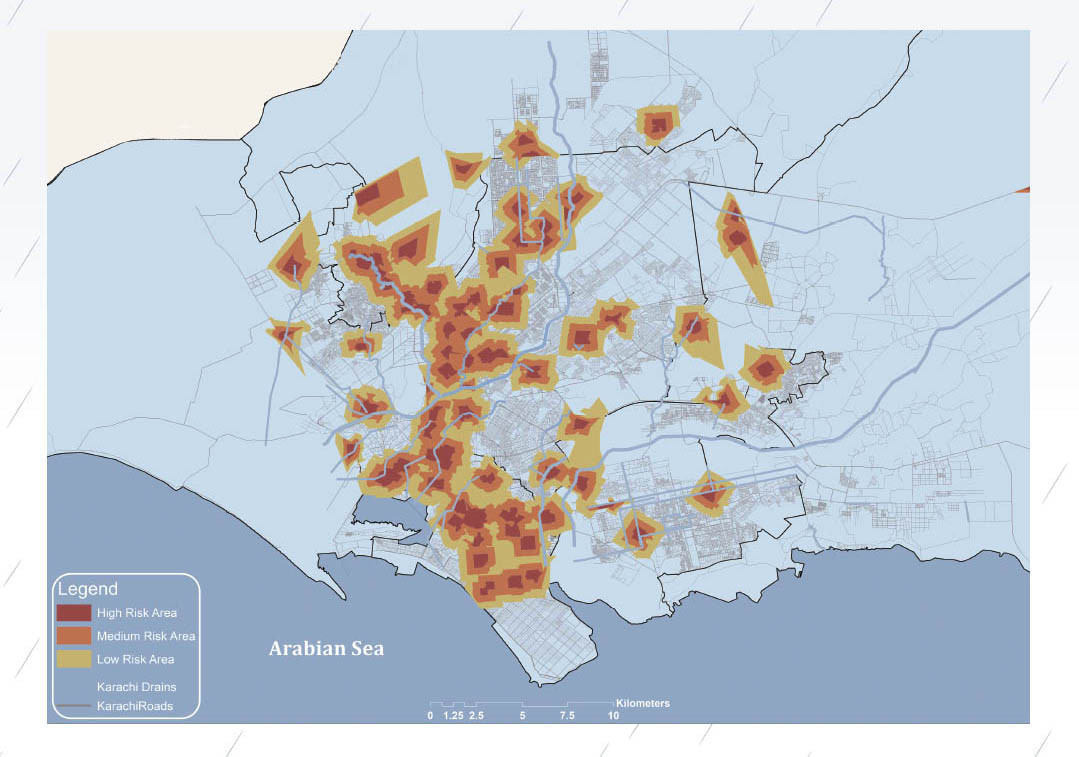

Additionally, Karachi's infrastructure is susceptible to damage from prolonged downpours, which might cause problems with utilities, communication, and transportation. Water damage to the electric distribution network frequently results in power outages, while impassable roads cause traffic jams and delays. Since there are many informal settlements situated in the low-lying, flood-prone parts of the city, the housing infrastructure is also in jeopardy.

Inadequate infrastructure has a substantial socioeconomic impact and disproportionately affects groups that are already vulnerable. Floods destroy houses and commercial buildings, resulting in financial losses for locals and impeding economic growth. Flooded places increase the risk of health dangers such waterborne infections, which exacerbates the situation of marginalised groups.

The city that produces 16,500 tons of waste every day has no proper system of disposal and is mainly being dumped in rain streams that are too untreated. “When half of the garbage is being dumped in the rain streams untreated then what do we expect the rain to offer us?” Anwar added. With the stream being blocked with garbage, the city gets flooded with the overflow whether the rainfall is 80 mm or 40 mm.

One major solution to this problem is to establish low-income housing schemes for the poor so that they can settle there and move away from the water streams. “No matter what new infrastructure, construction or nullahs are made, nothing can bring change until a low-income housing scheme is made and all the displaced people who are living on the streams, and have encroached the surrounding, are relocated. When the water gets a proper way to flow, the flooding will get better,” said Anwar. “There is no land owing because there is no regulation of that so anyone can put up temporary tents near nullahs and then they can't be removed that easily.”

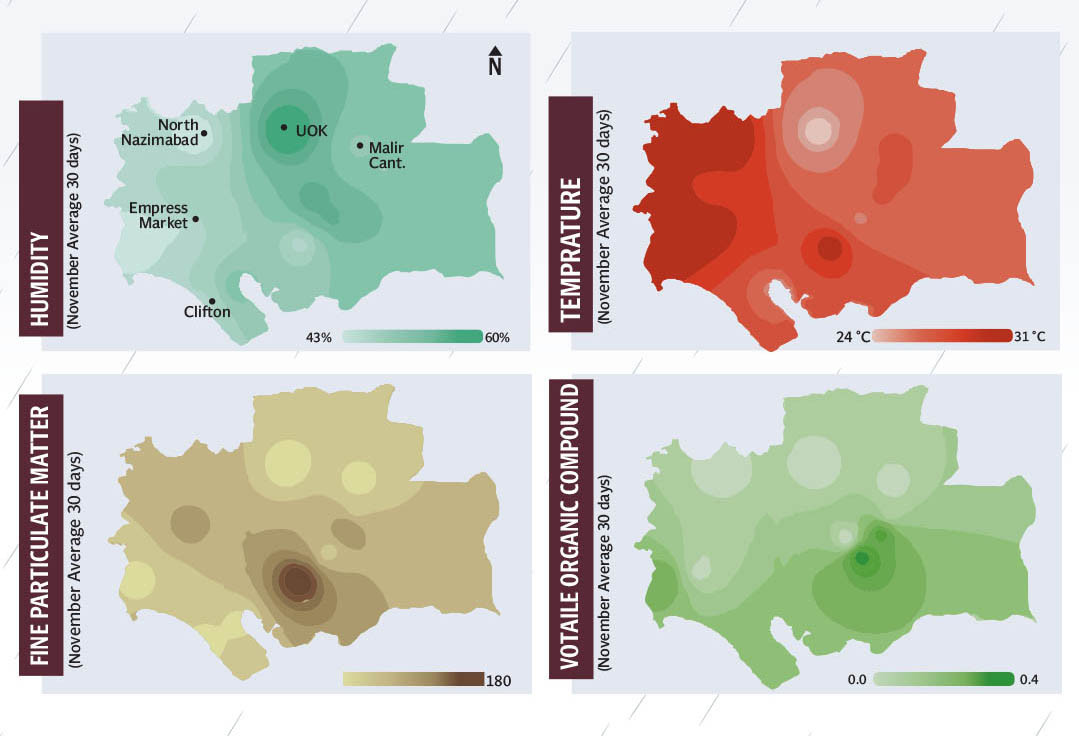

Rain and infrastructure in Karachi create several issues that call for a multifaceted solution which includes investments in urban planning, infrastructure development, and disaster preparedness. “Doing just one thing cannot help multiple problems that the city faces,” Anwar pointed out. Receding greenery is a major factor in urban flooding. The green spaces in Karachi are ending which used to help in buffering the floods naturally because green spaces worked as an infiltration system. But we have concretised the city so much and even the new society and housing schemes do not have any proper drainage system that only adds to the already existing issue.

Unlike a well-planned city, Karachi does not have well-made roads and that puts pressure on the drains too. The city gets flooded not only because of rains but because of multiple factors from roads, clogged drains, waste dumping, to name a few. “Roads are not made well in slopes so water doesn’t flow well to the drains and remain on the roads,” said Toheed. “For that matter, it won’t help even if you improve the sewage system or keep building storm water drains. The road conditions and construction remain the issue.” He suggested that whenever a new road is constructed or new carpeting is done, it must be kept in mind that road has a slope to allow water to flow and not collect on the road, while the roadsides should have storm water drains so the roads will not get flooded.

To make Karachi more resilient to withstand prolonged periods of rain, it is imperative to make investments in the drainage system's extension and modernisation. This includes installing new drainage channels, cleaning and de-silting existing drains, and incorporating sustainable drainage techniques like permeable pavement and rainwater collection. The Defence Housing Authority (DHA) started a new construction project with a drainage system but that too has been prolonged and the second monsoon is coming up now. Despite spending billions on the project, the city still floods and the construction is still ongoing. “The project can be one aspect but it alone cannot simplify the matter until all matters are resolved,” Anwar said.

Despite annual flooding, Karachi frequently lacks efficient catastrophe preparedness and response systems. The absence of emergency shelters, evacuation routes, and early warning systems leaves locals exposed to the effects of flooding. “Low-lying areas where roads are on different levels and sewerage levels are different creates another kind of catastrophe. For example, in DHA, the Manzoor Colony nullah is quite wide until Akhtar Colony but as it proceeds towards the outfall, the nullah narrow downs where it meets the sea,” Toheed told. Ideally, the width of a nullah should be more toward the outfall.

Ways to enhance infrastructure

Protecting Karachi's infrastructure from the effects of rainfall requires enforcing zoning laws and preventing encroachment on natural drainage channels. Green spaces and wetlands serve as organic flood barriers and hence should be given top priority in urban planning. “Reducing the risk of flooding and drainage obstructions requires improving solid waste management procedures. Regular garbage collection, recycling programs, and public awareness programs to encourage proper waste management are some examples of this,” said environmentalist Ashfaq Umer.

Throughout the past 40 years, planning laws and rules have been thrashed by builders, private developers, local, provincial, and federal government officials without any kind of accountability.

Numerous urban planners have raised the crucial issue of the lack of quality engineers, planners, and designers tasked with managing drainage system upgrades and infrastructure. It has frequently been argued that planners and engineers with degrees are not instructed in "social engineering" or the costs associated with evicting people. “What are we teaching the new engineers, because no matter what we no one is following any law in the country and construction business,” questioned Umer. He added that visionaries like Parveen Rahman warned of such chaotic aspects years ago but there is no visible will to make this city livable.

Planning for resilient infrastructure design can lessen the effects of periods of intense precipitation. To reduce damage and disturbance, infrastructure projects should include elements like elevated roads, flood barriers, and waterproofing techniques. “As for the housing societies, even roads are mainly built without proper drainage system or pipes to at least flow the rainwater that causes road damages,” shared Umer.

Developing resilience at the local level requires including the community in disaster preparedness and response activities. Campaigns to raise public awareness of emergency evacuation protocols, flood risk mitigation, and early warning systems can enable residents to take preventative action to safeguard their properties and themselves during periods of high precipitation. “Building infrastructure can do half of the work but also awareness about the subject is required where people are educated to not throw garbage or encroach on nullahs, warning them of possible flooding that can be life-threatening,” the environmentalist said.

To effectively execute comprehensive solutions to Karachi's infrastructural problems, government agencies, policymakers, stakeholders must effectively coordinate and collaborate. “Government entities can work on international collaboration, public-private partnerships, and technical know-how to mobilise resources and expertise for infrastructure development projects to help Karachi perform better in rains when they hit with full force. For example, February statistics show that we received record-breaking rainfall as it rained more than usual for February,” Umer shared.

“The dynamics are complex and ongoing projects will help in the future but they can only work well when the water reaches them. If the rainwater does not reach these lines from the mid city they won’t help much,” Toheed argued. He pointed out that even if Lyari River, Gujjar nullah, and others are well maintained, if the water does not reach Lyari River, then it will not flow to the sea. “We have to ensure that glitches such as solid waste are removed from the waterways and for that Karachi Metropolitan Corporation, Karachi Water and Sewerage Corporation, Sindh Solid Waste Management Board, and all other agencies such as cantonments should come on one page. Otherwise, projects costing billions of rupees will be of no use,” he concluded.

Inadequate infrastructure exacerbates the effects of high rainfall events on Karachi, where rain and infrastructure are closely related. A comprehensive strategy that includes investments in solid waste management, urban design, drainage infrastructure, and community involvement is needed to address these issues. Karachi can increase its ability to withstand rains and guarantee a safer, more sustainable future for its citizens by putting sustainable ideas into practice and encouraging cooperation between stakeholders.