Unlike the rest of Pakistan which has only four recognised seasons; summer, winter, spring and autumn, Lahore, the City of Gardens has another distinct season. Since the ban on kite flying in Lahore, this conventional Basant Bahar time is now marked as the season of literary festivals, craft exhibitions, book fairs and art exhibitions.

The Lahoris’ love for mela thelas [fêtes and fairs] has so far been unmatched. Equally unique are the more recently introduced public art projects that have allowed Lahoris to think of art as a collective social activity adding to the charm of the said fifth season.

To own the city, embrace its rich cultural heritage, nurturing the creative spirits of its residents while advancing on the ideals of public art, this year the season began with an inaugural show at the newly renovated gallery, The Barracks at the famous Nasir Bagh.

The show is significant for several reasons. One, it is the solo of an internationally acclaimed artist and maestro of contemporary miniature painting, Imran Qureshi. Two, it enhances the ultimate scope of public art in the city. Three, it adds to the historic value of the location, Nasir Bagh — the hub of many socio-political activities. Fourth and perhaps foremost, is the involvement of the Pakistan Housing Authority Foundation, a government institution that broke the archetypal image of government offices and their red-tape culture.

Professing the vision of the current DG PHA, the Civil Defense Office at the Nasir Bagh was relocated to turn the dappled basement into a state-of-the-art gallery space. Consulting a space design and curation expert also facilitated the entire project. The final result, in the form of the meticulously created installation by Imran Qureshi, mindfully curated space by Imran Ahmed, attentively supervised by the DG himself and enthusiastically received by the public, speaks immensely of the artistic aptitude of the people of Lahore; the students of adjoining institutes, the visitors of the Town Hall, the petitioners of the District Courts or the wanderers of Lahore that come from all walks of life.

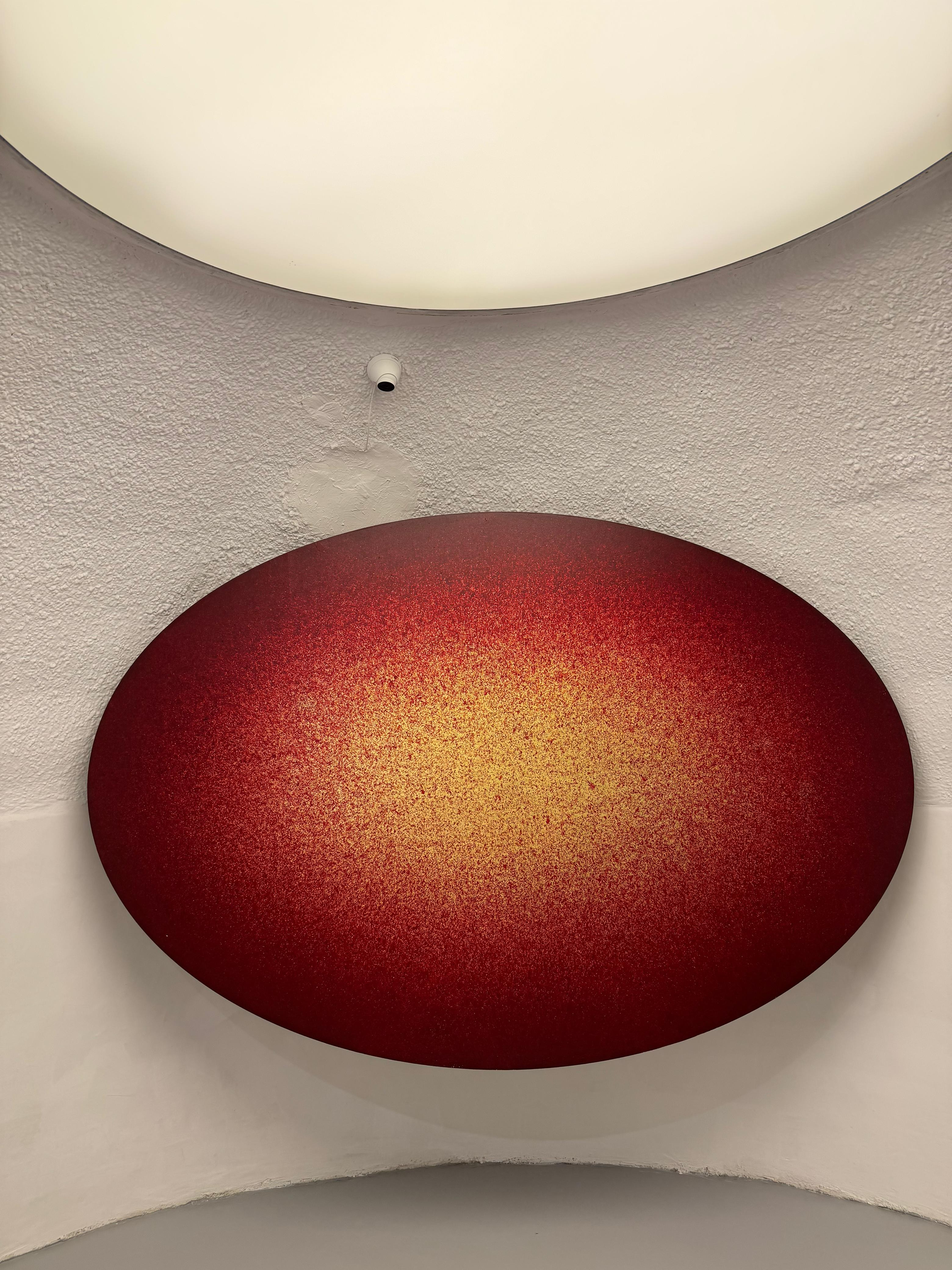

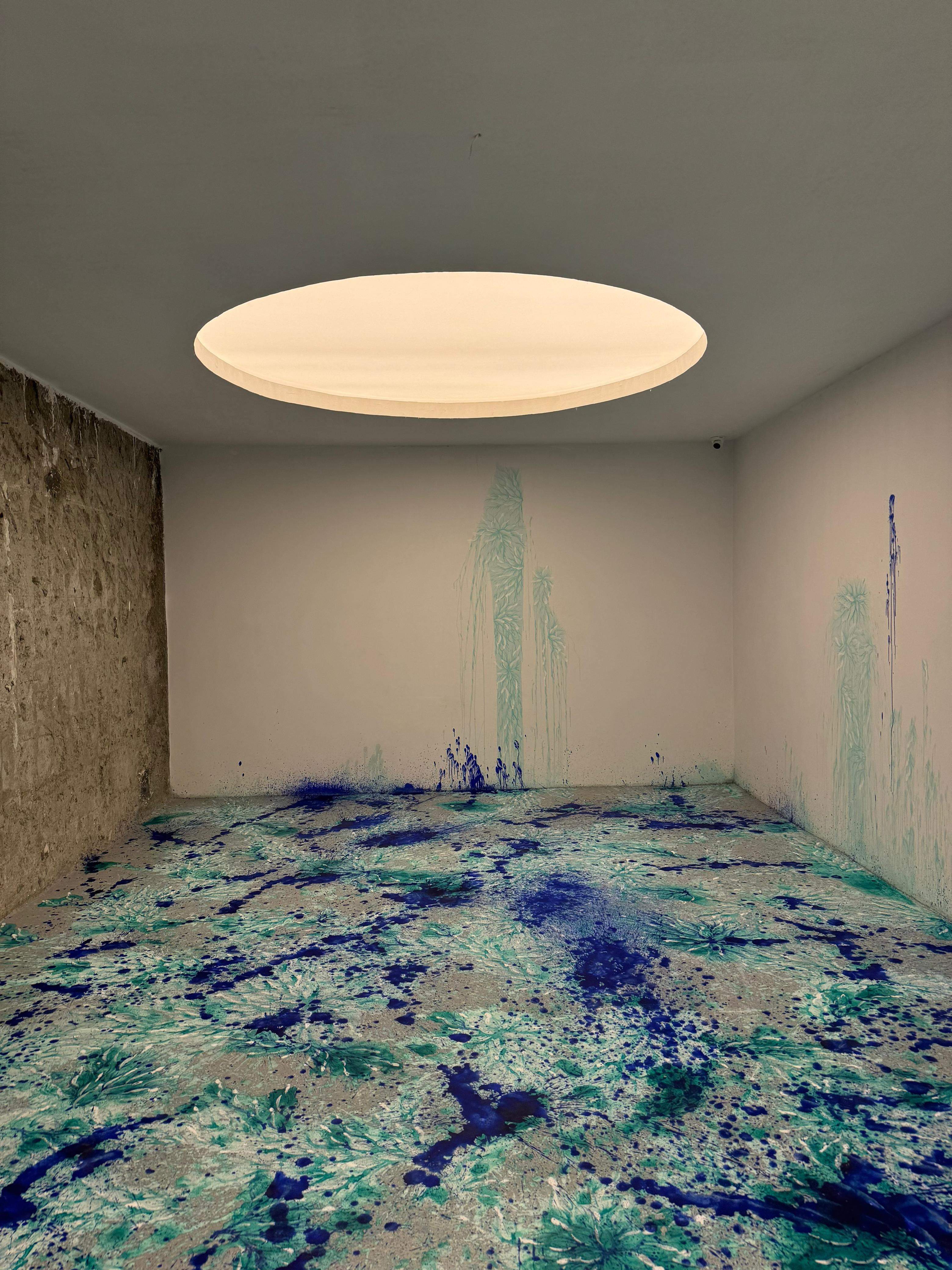

On the ground, The Barracks Gallery, originally constructed in 1948 as a bunker, is likewise a modest structure. The not-so-majestic door of the gallery opens into a meek staircase where Imran Qureshi’s garden welcomes the visitors. While the ones familiar with his practice are offered to be part of this extraordinary yet typical realm of miniature painting in the form of installation, the general public hesitates to step onto the painted foliage with the idea of not spoiling the great art. Once encouraged to enter they must feel cut off from the chaotic humdrum of The Mall and are transported to another world. The fanciful circular roofs with magical source of light adds to the overall drama creating an illusion of a garden scene with an open sky. Similarly, a two-channel video installed overhead and in-front allows one to be part of the running film.

The paintings on canvas and paper are conceived keeping the project in mind. The visual imagery successfully sustains the history of the location. The gilded missiles stand out in the compositions from the accompanying rich foliage due to their size and colour. This parallels the ambiguity of having a bunker in close proximity to colleges and in a public garden next to its fountain.

To a keen observer, the low height and circular dome-like structures of the gallery are also reminiscent of pre-historic caves where art is found hidden across chambers unravelling the mysteries of nature.

Theoretically, the entire set up is a physical manifestation of typical multi-perspective employed in traditional Indo-Persian painting. Very often scenes illustrating different segments of the story are composed within one picture space to complete the narrative i.e. visuals depicting what is happening outside the boundary wall, in the imperial court or deep inside the harem all are arranged systematically on one page.

In this context the solo show is just one big installation that upholds the legacy of the city, exhibits its cultural diversity, teaches resilience and determines the changing nature of art where the works break the bounds of the sacred exhibits in galleries and museums and become relevant to the larger public. The easy access, the interactive mode and the social engagement is the future of all art.

My first encounter with Imran Qureshi’s famous series of site-specific installations was through a bloody red photo, an aerial view, of Blessings Upon the Land of My Love, 2011, commissioned by Sharjah Art Foundation. For someone who has lived through the War on Terrorism, Qureshi’s installation was gruesome. The installation, triggered trauma and left me devasted and angry with the artist — my senior at the National College of Arts whose skill in miniature painting was exemplary, his style was innovative, his attitude towards art was meditative and his personality unpretentious.

I was angry because as a reminder of suicide bombings and bloodshed, the installation brought back the terror, fear and grief. After all who wants to relive the dreadful moments? A couple of years later, I had a chance to experience Qureshi’s The Roof Garden Commission at the Met Museum.

The time-lapse of two years allowed me to connect with the red splashes and seeping paints, illusory of blood and flesh, differently. It enabled me to channel my grief. I sat on the roof, tears in my eyes, finger tracing the vegetal motifs that sprout from the red paint. This essentially gave me hope and courage to anticipate life once again. I was convinced of Qureshi’s ability to console like a friend and his mastery over employing art as a medium of support and solace. I felt him extending his hand to take the affectees out of the psychotic state of constant fear and apprehension.

Later, in Qureshi’s practice the signature installation started changing its colour; the blood red turned blue, green and yellow on various occasions. This time at the Barracks, the splashes are shades of blue. Blue as a colour of water represents life. The life that sprouts in every direction in form of leaves and foliage promises abundance. It also lends the idea of endurance or more likely of a connection with eternity. In this context The Garden is an assortment of carefully selected notions and visions for its viewers to enjoy and ponder this season.

Sadia Pasha Kamran is a Lahore-based academic and a published scholar with a focus on decolonising art history for a global audience

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the writer