In the spring of 1954, Mir Muhammad Jamal Khan met my father, Maj Gen Syed Shahid Hamid, at the Lahore Horse Show and invited him to visit his Princely State of Hunza. When the invitation was repeated a month later, my parents decided to take the family on a great adventure to visit the legendary valley. Air Vice Marshal Bill Cannon, the second C-in-C of the Royal Pakistan Air Force, and his wife decided to come along.

The journey took a lot of preparation as it involved travel by plane, jeep, and ponies and a month’s stay. My mother had seen enough mountaineering expeditions at Rawalpindi to know what and how to pack for a long trip in the Karakorams.

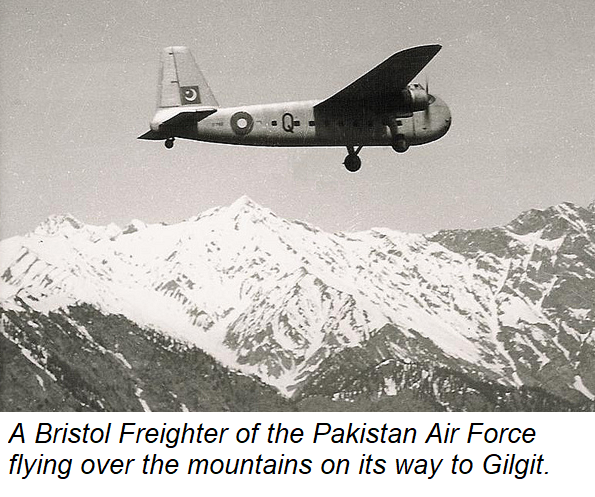

Ultimately one early morning we boarded a noisy Bristol Freighter for Gilgit that was minus its doors because it had flown supply missions in the Northern Area. My memory of the hour-and-a-half long bitterly cold flight is sitting in a bucket seat wrapped in a blanket. I was too young to remember anything more and even if I did, I could never describe the flight more eloquently than the well-known author Ian Stephens in his book Horned Moon.

“The dial shows 11,000 ft. A steep snow-powdered forested crest soars on our left….. the climb ceases. A shaft of sunlight arrives. On our right much bigger snow-peaks emerge, then wrap themselves again in clouds. Ahead is a grey misty bumpiness; we edge left to avoid it, pass very low over a snow-topped hill; beneath I see sunlit green deodars, vertical and tall on the slopes. A horrid blackness impends on our right, then moves away from us, and for a while we proceed in clear tranquil air. We are over the winding Indus now; it is narrow and swift, sunk deep in a grey cleft, the glacial jade-green waters sometimes white-streaked with rapids”.

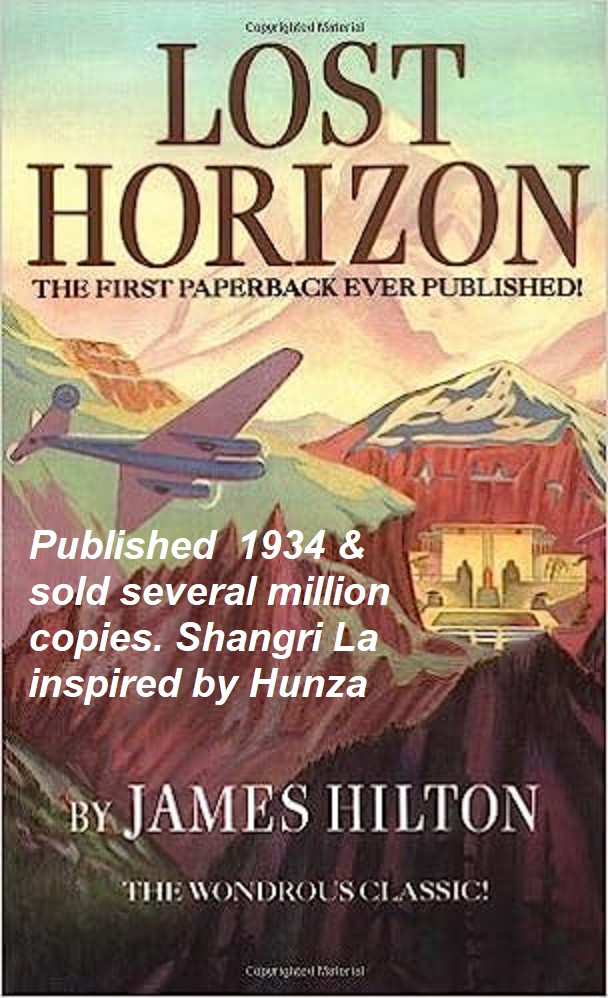

In 1934, James Hilton wrote his best-seller Lost Horizon which contains a description of the mythical Shangri-La. It closely matches the scenic Hunza valley which Hilton had visited only a few years before writing the book.

We were received by the Political Agent (PA), the imposing Muhammad Jan who accommodated us in the famous ‘Residency’ in Gilgit from where the British had administered an area the size of France. While waiting for Cannon, we fished for trout - some of the fish weighed up to eight pounds. Muhammad Jan did not believe in reeling in his catch. With a line that was strong enough to land a large Mahasher, he would whisk the unfortunate trout straight out of the water with a strong jerk and it would sail over his shoulder. An ever-ready attendant standing behind would unhook it and Muhammad Jan would cast straight back.

The trout had been introduced by another famous PA, Colonel Cobb who was also keen on polo and established several polo grounds all over the Gilgit Agency, including one at Hunza. Ultimately, the Air Vice Marshal and his wife Tiddler arrived early one morning, after a non-stop night flight all the way from Karachi, in another Bristol Freighter. Cannon knew the region well as he had commanded a squadron of Wapits on the Northwest Frontier in 1937.

The first leg of our journey to Hunza was 60 km by jeep to Chalt. The track ran along the River Hunza on the opposite bank to where the Karakoram Highway now runs. Ahead of the beautiful vale of Nomal, it became extremely hazardous and traversed a wide scree of crumbling rock called the Chaicher Pari. The boulders hurtling down from thousands of feet created a dust cloud that filled the valley. At Chalt, where the river swings eastwards around Rakaposhi, we stopped for the night. Chalt was a trading post with herds of ponies and yaks on their way to or returning from Misgar on the border with China.

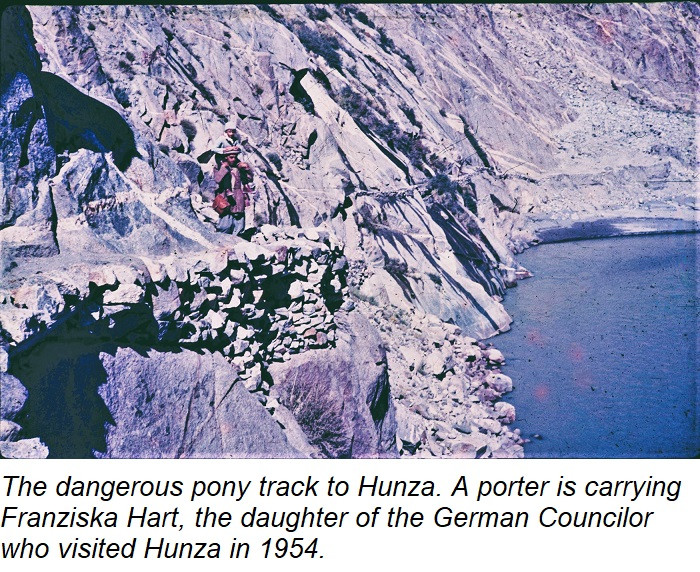

The next morning, we transferred to ponies for a difficult leg of 12 km to the rest house at Maiun. Danger and security alternated on the narrow track that at times ran along a gut-wrenching precipice 1,000 metres above the river and then, in a series of steep hairpin bends, entered soothing fields of green and orchards.

I was oblivious to the danger as I snoozed in a ring saddle that had been brought from Rawalpindi but my elder brother Hasan trusted his two legs more than the pony’s four and walked all the way. Tiddler insisted on remaining in the saddle even down the most dangerous descents and Shahid Hamid admits that he had never met a person with more guts and so indifferent to the hazardous journey.

The caravan entered the Mir’s territory at Hindi where the local band struck a wild tune while it was received by the elders who escorted it till the end of the village. The village lane was lined by peasants presenting baskets of apricots and mountain apples as a welcome gesture and they were hurt if some of their offering was not accepted. This ritual was repeated in every village along the way.

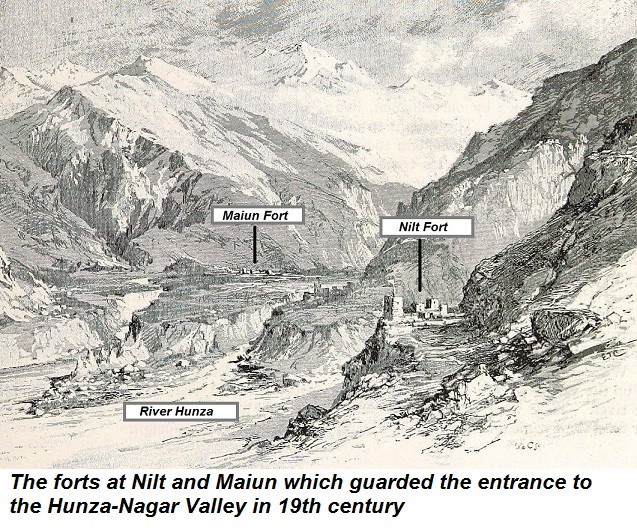

Sitting on the lawn of the Maiun Rest House that evening, we weary but happy travellers relished our first view of Rakaposhi rising 19,000 feet from the river to its crest by stages – fields and orchards followed by forests of fir, mountain meadows, and finally snow fields topped with ice cliff. Only 60 years earlier, the forts at Maiun and Nilt, across the river, guarded the entrance to Hunza-Nagar and were stormed by a force of 1,000 under Colonel Durand. The evidence of fierce resistance mainly by the tribe of Nagar was the three Victoria Crosses (VCs) awarded to British officers and several Indian Orders of Merit which was the equivalent of the VC to the Native troops.

When a rebellion broke out in Chitral four years later, the newly appointed Mir Nazim (the grandfather of Mir Jamal), assisted the British with troops and a large body of porters who hauled the guns over the Shandur Pass in deep snow. The British trust in the Mir deepened and, in 1912, he was asked to raise a Corps of Scouts, two companies strong, based in Gilgit, with his son Ghazan Khan (Mir Jamal’s father) as the first Subedar Major. This force was subsequently given the title of the Gilgit Scouts which, in 1947, overthrew the Governor appointed by the state of Jammu and Kashmir, and declared accession of the Gilgit Agency to Pakistan.

The next and final leg of 38 km was no less dangerous in its initial stage, and the caravan had to frequently halt to avoid boulders tumbling down. The speed with which the locals moved was admirable and before the road was built to Chalt, they could trek from Gilgit to Hunza in a day. At Murtazabad, we finally entered the lush green valley of Little Hunza, with its orchards and irrigation channels that had been laboriously constructed over decades by diverting the mountain streams. We were received at the rest house at Aliabad by Prince Ayash Khan, the Mir’s brother, and Ghazanfar, the heir-apparent who was clad in a naval uniform. Six kilometres ahead, the Mir with his entire family were waiting for us outside their residence at Karimabad.

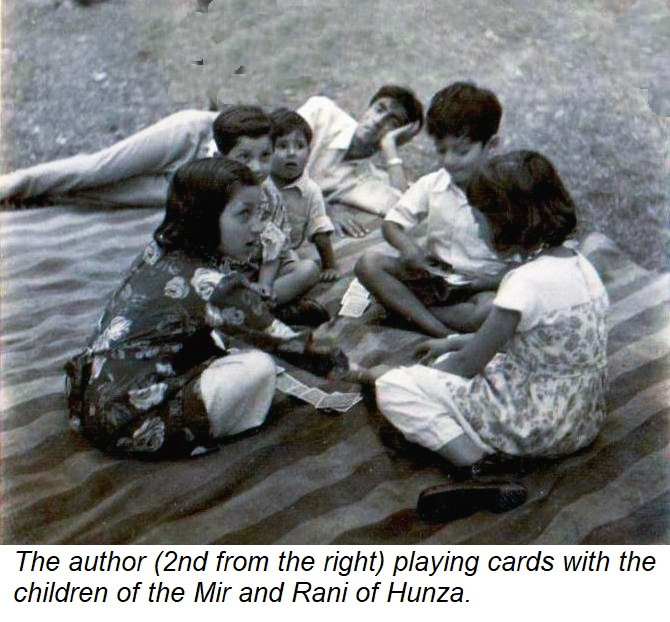

Mir Sahib, as he was universally addressed, exuded a commanding presence — a testament to the legacy forged over eight centuries of rule by his family. He became Mir at the tender age of 22 when his father Mir Ghazan Khan passed away in 1945. Two years later, he married Shams-un-Nehar, a princess from the State of Nagar. She was addressed as Rani Sahiba and was soft-spoken with an endearing smile. The Mir and Rani Sahiba had nine children, all of whom were reared by foster parents, one from every village. It was an admirable way of uniting the community and the children used to spend the night in their foster homes. His six daughters were excellent company for my two sisters and myself.

Adjoining the Mir’s residence was a large freshwater pond in which the boys swam during the day and the girls were allowed in the evening in their shalwar kameez. Shahnaz, my eldest sister, had recently learnt swimming and jumped into the pond little realising that it was fed by a stream straight down from the glaciers. By the time she struggled out, her teeth were chattering and her lips were turning blue.

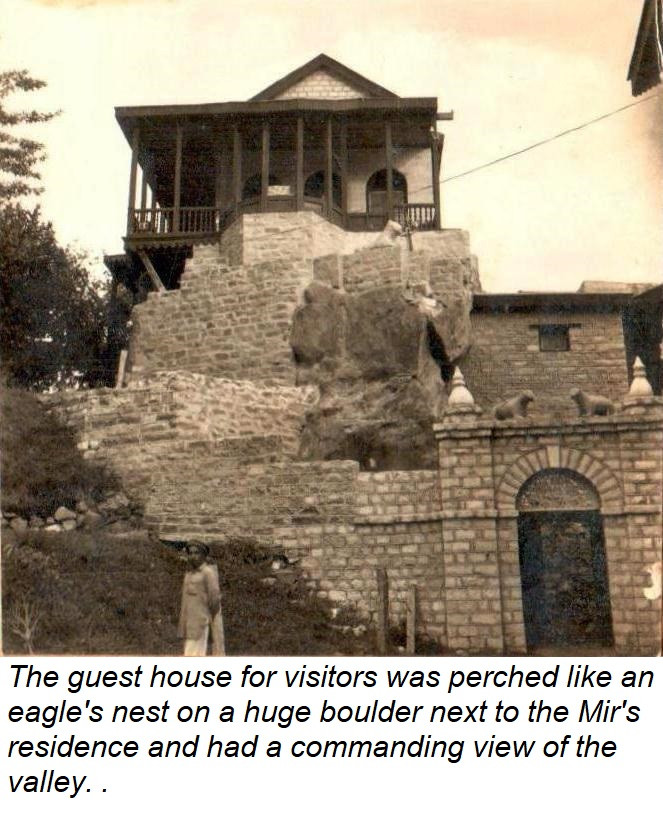

The three weeks that were spent with the Mir and his gracious Rani were idyllic. The guest house for visitors was perched like an eagle's nest on a huge boulder next to Mir Sahib’s residence and had a commanding view of the valley. Shahid Hamid spent time sitting on its balcony consulting a treasure trove of books on the region in Mir Sahib's library and compiling the early chapters of a book on Hunza. Much of the material in this article has been extracted from his book which was published as a tribute to the Mir after he passed away. The usual routine was a late breakfast followed by a ride or a walk through the fields and hamlets, lunch and siesta followed by a game of tennis, and finally an early dinner and a long night's rest. One of their most arduous tasks every evening was to decide the menu for the next day.

As visitors, our party had the opportunity to closely observe the lifestyle of a tribe that was portrayed in the most glowing terms by travellers and explorers. In The Burusho of Hunza, published in 1938, EO Lorimer writes, “There is something winning about the complete lack of servility in Hunza. The people are hospitable, courteous, and polite .. they own the soil, live their own lives, and can look the whole world in the face”. In his book The Mountains of Tartary, the great mountaineer Eric Shipton describes the Hunzakuts as “proud, loyal, brave and open-hearted.” In fact, in the opinion of Younghusband, the great explorer who was appointed as the Assistant PA in Karaimabad, the Hunza-Nagar Campaign would have been unnecessary if the British had maintained a closer personal relationship with the Mir.

The Hunzakuts lived a hard life, grazing their flocks and herds in the high pastures, repairing the water channels, and tilling their fields and orchards throughout the summer to survive the harsh winter. Their families were closely knit and houses well-tended. There were no rich or poor and, in bad times, all the neighbours chipped in to help those in distress. An appeal to the Mir for help was never ignored. The women were treated as partners by the men, unfaithfulness was rare and divorce was not a stigma.

Their diet consisted of milk products (fresh, sour, butter, cheese, and Ghee), and vegetables, both leafy green as well as roots, and were boiled in a small amount of water which was also drunk. There were no spices and salt was substituted by saline earth which was washed and added to the pot. A variety of fruits were part of their diet of which the apricot was the most important. It was the only source of sugar and was eaten fresh in summer and dried in winter and the kernel provided oil. During winter, the preferred diet was a hot porridge of dried apricots and whole-meal corn was baked in a variety of ways, sometimes with oil to make it into a cake. Grapes were never eaten but used for making wine, the famous ‘Hunza Pani’, which was only drunk in winter. Likewise, meat was eaten only in winter.

One of the highlights of the stay was a visit to the Baltit Fort which was located above the Mir’s residence and dominated the valley. When the British troops stormed Hunza, they looted the fort’s armory and its priceless objects that had been acquired over centuries. Valuable lamps, musical boxes from Paris, delicate Chinese pottery, Russian Samovars, and other objects of art were sold by the British to the bazaars in Gilgit to pay for the bounty to the troops who had taken part in the operation. Centuries-old manuscripts in Chinese, Turkish, Persian, and Hindi along with manuscripts of the Quran were sent to the India Office and are probably now in possession of the British Library. The fort was subsequently rebuilt and the Mir and his ancestors brought back some of its lost charm by richly furnishing it with Chinese silks, Yarkand carpets, and coloured prints from Kashgar.

The Mir himself lived in a comparatively modest but aesthetically designed residence. The living space on the upper floor was like a small museum and the shelves in the sitting room were adorned with autographed pictures of famous personalities who had either visited Hunza or the Mir had befriended in Paris and elsewhere abroad. In a storeroom below was the Rani Sahiba’s collection of Chinese Silk and tapestries which she showed my mother one day while I sat alongside. With a smile, she gave me something small from what looked to me like a treasure chest. I can’t remember what it was, but I cannot forget the gesture.

The Mir commanded great respect and was a fatherly figure. He governed his subjects simply and intimately and had a special relationship with them which was based on mutual respect. Next to his residence was his Audience Chamber where he spent most of the morning receiving a stream of subjects who brought petitions or disputes mostly dealing with the distribution of water which was their lifeline; all this set against the backdrop of Rakaposhi.

Mir Sahib was not only the ruler. The population of Hunza is Shia Muslims of the Ismaili branch and Mir Sahib had been nominated by the Agha Khan to look after the sect in the entire region of Central Asia. He was a world-wise and much-travelled man who was invited by the Agha Khan every year, along with his family, to meetings of their religious community in Paris.

The Mir had the honorary rank of major general in the Frontier Force Regiment and was a frequent guest at military functions. He was always accompanied by Prince Ayash Khan who acted as his secretary. The Prince had been given the honourary rank of a major in the Corps of Signals by the British. He had been trained in wireless at Mhow to look after the communication which included a telephone line that connected Srinagar with Misgar as well as a transmitter at Karimabad to report on any incursions by the Russians or Chinese. After Independence, the Mir extended the communication network throughout the state and in the evening talked to all his village headmen.

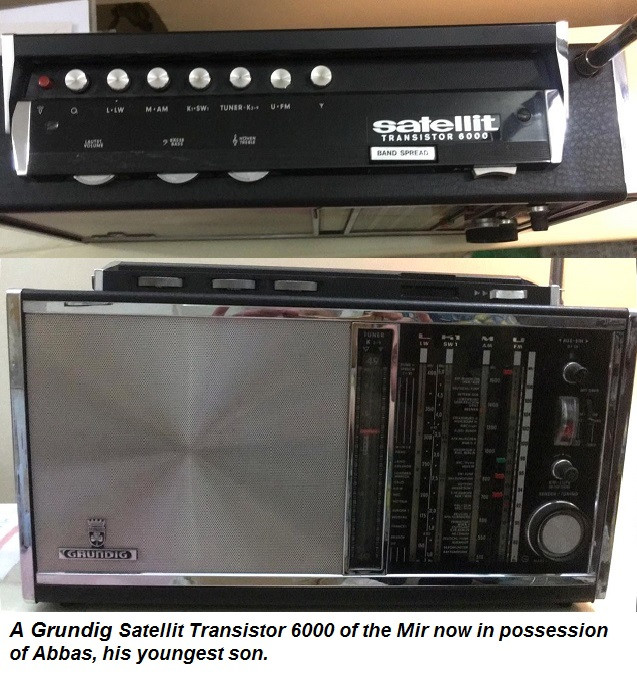

Both the Mir and Ayash Khan had a passion for radios which, considering the remoteness of the valley, was understandable. It was how they remained aware of what was happening in the world. I remember his American battery-powered Zenith Trans-Oceanic Short Wave Radio with a price tag of $100 (the equivalent of $1,000 in 2019). Some years later, the Mir also acquired what was considered the Rolls Royce of radios: the German Grundig Satellite Transistor 6000. It was highly engineered and intrinsically more complex than the Zenith and, in the 1960s, would set a customer back by $500.

Before our departure, we were all presented ‘Choghas’, a traditional gown woven from sheep down, and the ones for the females were intricately embroidered with bright floral patterns. The Mir and his Rani were generous to a fault. As our caravan headed back, Shahid Hamid noticed that one of the ponies was carrying a large roll that was not part of our luggage. It was a carpet that had adorned Mir Sahib’s sitting room that my mother had one day admired, and he sent it along as a gift.

Over the next two decades, our families became very close more so because Mir Sahib constructed a house in Satellite Town in Rawalpindi where his family would winter.

After political disturbances in Hunza that were engineered by then prime minister Zulfikar Bhutto in 1974, the state was annexed to the Northern Areas under the federal government. Mir Jamal was inconsolable. “What will become of my people?” he lamented to his friends like my father. Ironically, the last Mir of a tribe renowned for their longevity passed away at the relatively young age of 64. A way of life that had been preserved for centuries had been demolished and he died of a broken heart.

Syed Ali Hamid is a retired Pakistan Army major general and a military historian. He can be contacted at syedali4955@gmail.com

All facts and information are the responsibility of the writer