Winning hand of king's party

No ruling party in four elections secured over 33% of votes, creating manoeuvering space for establishment

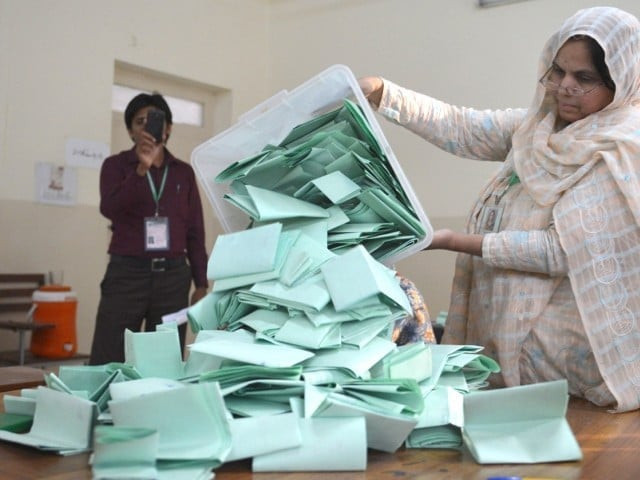

The result management system in Pakistan – which remains a festering source of most electoral controversies – seems to have a mind of its own, leaving most voters scratching their heads at the end of the polling day and election outcomes shrouded in mystery.

The “king’s party” ends up playing a winning hand, snagging more seats than its fair slice of the voting pie.

Regardless of candidates' meticulous calculations and prevailing conditions, the outcome of elections seems to defy both logic and proportional representation.

The number of votes for mainstream parties frequently fails to align harmoniously with the seats they secure.

In this political chessboard where the establishment pulls out all the stops, a comprehensive analysis of the last four elections reveals a pattern where the “king’s party” bags more seats than its proportionate vote share on the polling day.

The establishment's playbook includes deft pre-poll and post-poll strategies, including seat adjustments, vote division using "manufactured" smaller parties, and the creation of splinter groups, to influence results in favour of particular parties.

Notably, none of the major political parties forming the government after the last four elections managed to secure more than 33 per cent of the total cast votes, allowing ample room for establishment manoeuvres.

When traditional methods prove insufficient, rejected votes become a strategic tool, especially in closely contested races.

Rejected votes in many cases surpass the margin between the winner and the runner-up, and this trend is on the rise with each election.

2002 general elections

Examining the 2002 elections under then-military ruler General Pervez Musharraf, the Pakistan Muslim League-Quaid (PML-Q) emerged as the largest party with 78 seats.

This happened despite the fact that they secured fewer votes than the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), which participated in the elections under the banner of Pakistan Peoples Party Parliamentarians (PPP-P).

The opposition vote was further neutralised through alliances, with smaller pro-establishment groups securing seats beyond their vote share.

The PPP had bagged more votes compared to the PML-Q.

The king’s party, the PML-Q, had received 7.5 million votes compared to PPP’s 7.6 million.

The PPP could get 63 general seats.

Nawaz Sharif’s broken PML-N secured 3.4 million votes, which by percentage of votes was 12 per cent of the total polled votes, and bagged only 15 seats.

This opposition vote was neutralised through a new alliance of some smaller pro-establishment groups contested on the platform of National Alliance, which got 1.3 million votes (five per cent), but it bagged 13 seats.

Most of the 28 independents joined the PML-Q, strengthening the party's tally to increase its number for reserved seats for women and non-Muslims.

When the PML-Q and the National Alliance still could not make the required numbers, a new splinter group from PPP-P comprising many of the party's stalwarts from Punjab was created with the name Pakistan Peoples Party-Patriots to join the coalition government.

In the 2002 elections, Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) had bagged only 3.3 million votes (11 per cent) but secured 45 general seats.

The MMA served as friendly opposition and helped pass a constitutional amendment package Legal Framework Order (LFO) that validated all the actions of the military ruler.

2008 general elections

In the 2008 elections, held amid the tragic assassination of Benazir Bhutto and the declining rule of General Musharraf, of the 80.7 million voters in the electoral rolls, 35.6 million polled their votes with 44 per cent turnout.

The PML-Q was not the first choice of the powerful quarters this time. Led by Asif Zardari, the PPP secured 10.6 million votes which was 30.7 per cent of the total votes polled across the country on the election day. With 89 general seats, it emerged as the single largest party in the National Assembly.

On the other hand, the PML-Q this time bagged 7.9 million votes (23 per cent) but it could muster only 42 general seats while the PML-N though secured 6.9 million votes (20 per cent), however its tally of seats was 68- showcasing a discrepancy in proportionate votes versus seats.

Later on, the PML-Q had to join the PPP-led coalition government which was initially formed with the help of independents and smaller groups.

2013 general elections

The trend continued in the 2013 elections, which saw 55 per cent turnout.

Imran Khan-led PTI for the first time emerged as a serious contender.

On the polling day, the PML-N bagged 14.7 million votes with the highest percentage of the last four elections - 32.7 per cent of the total votes and secured 124 seats in the lower house of parliament.

Read: Elections 2024: Parties race to woo key youth voters

The PTI secured second highest 7.7 million votes (17 per cent) and bagged 26 general seats while the PPP though had 6.9 million votes (15 per cent), it bagged 31 general seats – again a discrepancy in proportionate votes versus seats.

Similarly, the combined tally of votes of the PPP and the PTI was almost the same as the PML-N, but if one combines their number of seats, they were much less, emphasising the disparities.

2018 general election

The 2018 elections witnessed a shift in establishment preferences, favouring Imran Khan's PTI.

Of 106 million registered voters across the country, 51.7 percent polled their votes.

Imran’s PTI emerged as the largest party bagging 16.9 million (32 per cent) votes, securing 116 general seats. The PML-N which had falling out with the powerful quarters secured 12.9 million votes (24 per cent), however its number of general seats was only 64, while the PPP with 6.9 million votes (13 per cent) secured 43 general seats in the lower house.

Role of 'manufactured parties' and independents

In every election, novel strategies are employed to influence outcomes.

Independents consistently play a pivotal role, securing the fourth or fifth-largest votes and seats in the last four general elections.

In 2002, independents secured nine per cent of the total votes with 29 seats, supporting the king's party (PML-Q).

Religious party alliances, like the MMA, served as friendly opposition to facilitate smooth governance for the ruling party.

In 2008, besides other factors, including inside tussle with powerful quarters, sudden power and gas outrages affected the PML-Q vote while Benazir’s assignation had mustard sympathy for the PPP.

In 2013, the PPP had to suffer due to poor performance and was limited to Sindh.

The media campaign against the party, corruption charges, and general law and order in the country did not allow the PPP to campaign freely tilting the edge for the PML-N.

In the 2018 elections, the PTI was facilitated in every manner to ensure its victory.

Many electable from South Punjab were conjured in a "manufactured alliance" tagged as “Janoobi Punjab Mahaz” to later join hands with Imran’s party to form the government.

Khadim Rizvi’s Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) was there to dent the PML-N which had lost the blessings of the establishment.

Campaigning on the blasphemy card played against the PML-N, as it is estimated that the TLP cost the PML-N at least 15 seats in the National Assembly.

Still short of numbers, the PTI had to rely on smaller pro-establishment groups like MQM, PML-Q, BAP, GDA and independents to form a fragile government which crumbled when these groups withdrew their support.

Of 13 independents who secured 11 per cent of the votes, the majority joined the PTI.

In 2008, around 30 MNAs were elected as independents securing nine per cent of the votes while in 2013, 29 independents got elected securing 14 per cent votes.

These independents had a crucial role to play in the formation of the PPP and the PML-N’s respective governments at the Centre.

Rejected votes

Despite perceived increasing awareness about the election process, the percentage of rejected votes has steadily risen.

In 2002, approximately 2.5 per cent of the votes were rejected; in 2008, 2.7 per cent; in 2013, it was 3.11 per cent, reaching 3.13 per cent in the 2018 elections.

Though seemingly a small percentage, rejected votes have had a significant impact on results, changing outcomes in many constituencies.

In the 2018 elections, 1.6 million votes were rejected, influencing results in at least 30 National Assembly constituencies.

In many constituencies, the number of rejected ballots was greater than the margin of victory during the last four elections.

ECP’s election management system

While technology was expected to enhance the integrity of elections, this has not been the case in our situation.

In the 2013 elections, the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) implemented a system that captured the thumb impressions of each voter to prevent fraudulent voting.

However, when the results faced scrutiny, the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) system struggled to trace a significant number of contested thumb impressions, citing various technical reasons.

In 2018, the ECP introduced what it called an integrated ‘Result Transmission System’ (RTS) which crumbled within a few hours after the vote count started.

For the 2024 elections, the ECP is introducing a new system tagged ‘Election Management System’ (EMS), developed by a private company, to compile results electronically along with manual count.

The ECP had its first large-scale mock test of the new system only a week ago – around two weeks before the polling day.

It is to be seen how successful the new system would prove in bringing transparency in vote count.

As Pakistan braces for the upcoming elections, understanding these intricacies becomes crucial in deciphering the political chessboard where manoeuvring and strategy shape electoral outcomes.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ