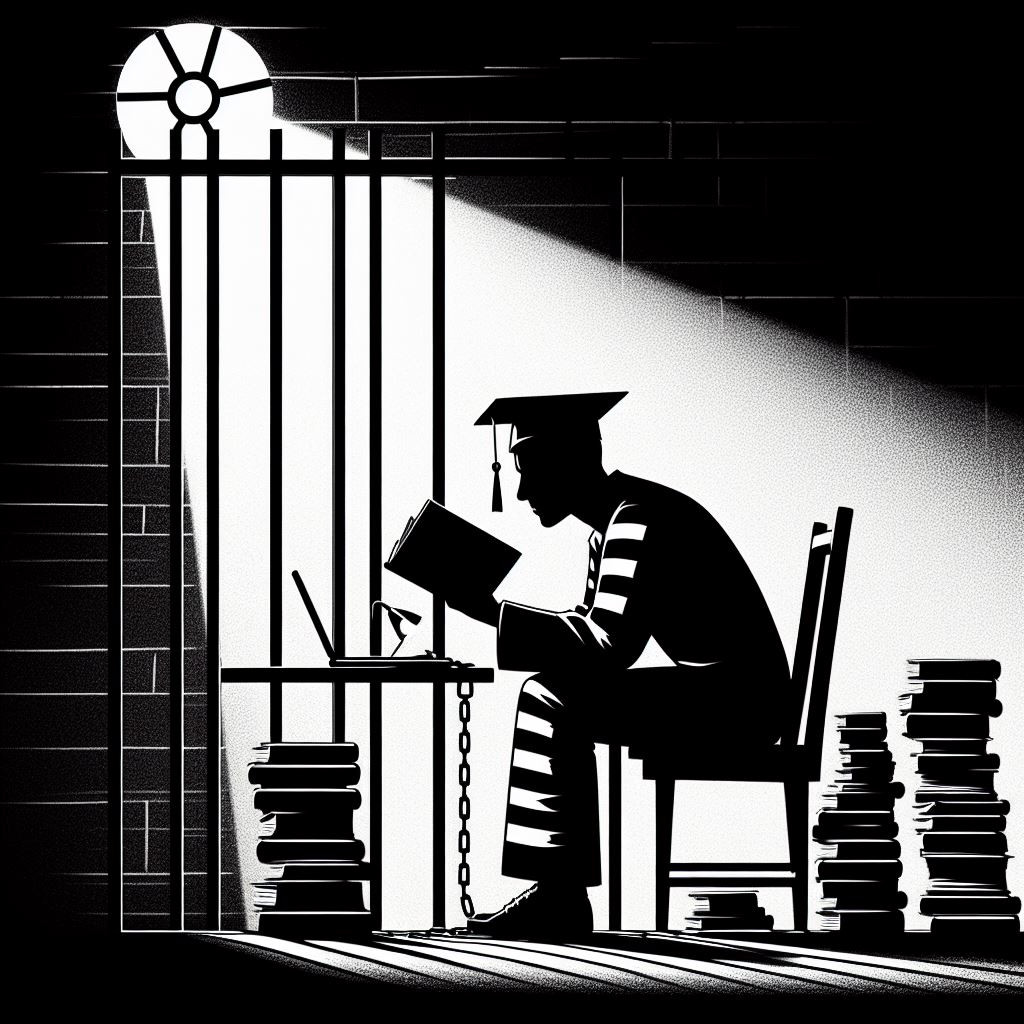

When prisoners are released after completing their sentence, they face an environment that is challenging and actively deters them from becoming productive members of society. They struggle to find work, and people think they are dangerous and bad. Hence ex-prisoners are rejected from the society they are trying to reenter. This social rejection can have such a strong effect on former prisoners

Often, ex-offenders are rearrested. It is also seen that recidivism or the re-arrest, reconviction, or re-incarceration of an ex-offender within a given time frame harms both the families of inmates and society in general.

Once prisoners are released, it is more difficult for them compared to the general populace to find gainful employment, and generally function in society. Often viewed as sub-citizens, ex-offenders are perpetually punished for crimes. The causes of these restrictions are systemic and affect ex-offenders at all levels of society.

The total prison population of Pakistan is 87,712 (August 2022, UN Report), while the prison population rate (per 100,000 of national population is 38, based on an estimated national population of 230.02m.

While everyone else sees prisoners as aliens and culprits, Ehsam Ullah Baig sees them as human beings and a part of the society. In line with his views about prisoners, Baig laid the foundation of The

Jail Project along with friends in 2018 in Gilgit-Baltistan. But before he could proceed any further, the pandemic arrived. Fortunately, when circumstances got better in 2022, he restarted the project.

What is The Jail Project?

“We give prisoners two options, says Ehsam Ullah Baig, who heads The Jail Project. “They can either avail the opportunity to get education or learn skills while they are in jail.” Since the initiative targets prisoners’ betterment in society, facilities are provided to them for education, learning skills and personality development.

“When we started the project, we also came across some prisoners who were well-educated,” says Baig. “A couple of them had done their masters and one of them was an engineer.” Presently, there are some 300-400 prisoners in the Central Jail Minawer, Gilgit, but it is up to the prisoners to benefit from this opportunity.”

“There are no hard and fast rules to enroll in this project,” says Baig. “By law, it is a prisoner's right to get education in jail but unfortunately, until we took the initiative, there were no facilities available to them in jail for doing so.”

Initially, the programme turnout was quite significant, as out of around 300 prisoners, 100 enrolled with almost 50% opting for education and the rest went for skills. The said they wanted to utilise the time for something constructive in their lives and had opted for the project for skill training or acquiring education because they didn’t want to repeat the mistakes that they had made in the past.”

The prisoners who did not participate in the programme said that they were content with their status in regard to skills and education.

“We cannot tell you exactly who became a better individual after the programme,” says Baig. “But with the passage of time we could see an obvious change in their thought process and behaviour. We started this programme for their betterment, and that is what we focus on.”

How it started?

“When some fellows in my neighbourhood returned after completing their imprisonment, I realised that they were not able to fit in the society anymore and had difficulties being accepted,” shares Baig. An idea sparked in his mind and after some thought, he got some like-minded people together and pitched the idea to Naveed Ahmed, the District Commissioner of the time.

“We had no trouble in getting permission to start this project,” says Baig, “as previously, we had worked on a few projects for the government, so there were no credibility issues.”

Our motive

“Our core motive is that after being released from jail, the prisoners can re-adjust in the society and become good people and responsible citizens,” says Baig. “But there are no sources available to work on their personality while they are in jail, nor any kind of activity that keeps them connected to the outside world.”

Hence after being freed from jail, they feel a disconnect with the society. Once prisoners have completed their sentence, and step into the society, they are stigmatised as people who were previously criminals and are

considered dubious.”

This is why it is important to keep prisoners updated through education, conversation and discussions and activities with what was happening in the outside world, so that when they are set free, they don’t feel as if they have stepped out on the wrong planet.

“When you spend three, four or five years in jail, it is precious time lost while the outside world is changing all the time,” said Baig. It is essential for prisoners to know what has changed in the society, so they are prepared before they step out and survive in the new and changed environment.

“I believe that a jail is more of a rehabilitation centre, and not just a place for punishment,” says Baig, “This is the place where people get time to reflect and improve themselves. Otherwise, they feel lost and frustrated when they step out and may recommit crime and become habitual criminals.

How the project works

“We cannot provide a classroom atmosphere,” says Baig. “But twice or thrice a week, we arrange education and learning sessions for them.” Initially, Baig was not allowed to provide books and other material to prisoners, but with the passage of time as they came up with different ideas for education and learning, the prisoners were provided with books

and learning material.

With time, the project has progressed and presently, it works by connecting the prisoners to different education sources and government institutions.

“For prisoners who wanted to continue their education and attempt exams, we connected them to Allama Iqbal Open University,” shares Baig. For this, they have to apply to their superintendent and seek permission for exams.

“We work as vectors and facilitators, by connecting prisoners to the respective institutions that can help them.” For those who do not want to continue their education, ideas are pitched to the social welfare department to teach them skills.

Recently, Baig’s project team has met with the agriculture department to discuss introduction of activities such as gardening or kitchen gardening for prisoners. Presently, the rehabilitation and education project is working smoothly in the central jail in Gilgit.

“Logistically there are not so many expenses,” says Baig. “Initially, we spent from our pockets to buy books and stationery, however for connecting them to different institutes, there are no expenses involved.”

More than money and investment, the project demands a massive amount of time, because it takes time to build an image, trust and communication with prisoners.

“It is difficult to build a healthy conversation with someone who is in jail,” says Baig. “What kind of conversation would you expect from them? You cannot put your motive, or your plans in front of them straight away. First, you have to create a comfortable connection with them and then later you can discuss rehab ideas. Not just that, you also have to maintain your relationship with the staff of the jail. After a year or a couple of years, the staff gets changed and again you have to put in

an effort and build relations with the new staff.”

What’s next?

Baig runs the Pakistan Innovation Summit Education, a non-profit organisation, that works for education as well as several other projects with government, such as during the pandemic or floods. “We are working on a medical camp that will include blood screening and OPD,” shares Baig. “We will also try and teach them how to give first aid in an emergency although this type of facility is already available in jail.” Studies across the world indicate that education during incarceration has long term benefits for entire societies.

In fact, a report in the US suggests that individuals who participated in any form of educational programmes in prison were 43% less likely to return to jail. This is mostly because, among other factors, prison education has shown to have significant personal benefits in the form of higher chances of employment post release, greater political engagement and volunteerism, and improved health outcomes. On the other hand, ex-convicts who have low levels of education are often unable to find work or social support systems, thus increasing their chances of committing crimes and re-entering the prison

system.

Higher recidivism affects the entire population of a country because it diverts money and resources to the criminal justice system that could instead be spent on other community reform policies. Increased criminality also has intergenerational effects, with children of prisoners being more likely to have unstable family systems, lower economic resources, higher tendency of delinquent behaviour and eventually turning into criminals themselves. Investing on prison education, therefore, has a significantly high return value, saving taxpayers’ money that could be used in other development projects.

Maleeha Kiran is a freelance journalist and student of mass communication

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the writer

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ