"That's the thing about books,” Jhumpa Lahiri once said. “They let you travel without moving your feet."

I didn't quite understand Lahiri’s words until I stumbled upon a book that made me feel as if I was standing in front of the Gallery Sadequain in Frere Hall, Karachi, even though I have never visited Gallery Sadequain.

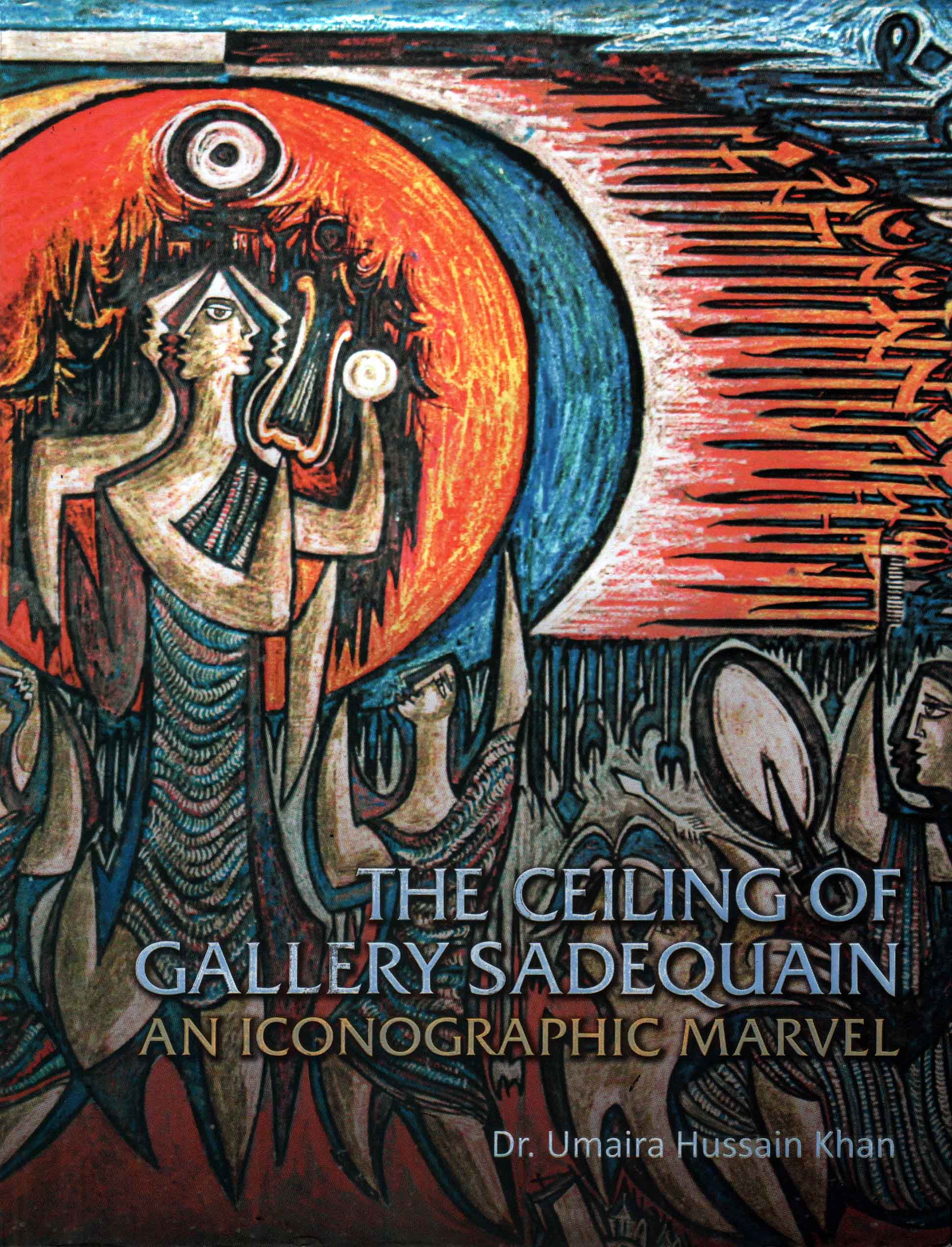

Dr Umaira Hussain Khan’s The Ceiling of Gallery Sadequain: An Iconographic Marvel, appeared to be a simple research journal that critically analysed the work on the ceiling of the gallery. But reading the book revealed that it tells a story of the soul of Sadequain's work.

Sadequain’s perception of the gallery

According to Khan, Sadequain wished to paint the ceiling of Frere Hall and associate his name with the building like Michelangelo did with the Sistine Chapel, even though it is a fact that Michaelangelo never wanted to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling. He was daunted by the difficulty of the task and made it clear from the start that he resented the commission, which had been imposed upon him by the imperious and demanding “warrior pope”, Julius II.

He came to know that Abdul Sattar Afghani, then Mayor of Karachi Municipal Corporation, wanted a redesign of Frere Hall's interior layout. Sadequain had already conveyed his desire to M. Arif, Chairman Balochistan Development Authority, who persuaded Abdul Sattar Afghani to allow Sadequain to paint the ceiling. Finally, on December 31, 1985, he got approval for the project.

The book narrated that Sadequain divided the ceiling into four cornices (A, B, C, D) and a central part. He wanted to deliver the project as soon as possible. However, the magical painter could not complete the ceiling as he passed away on February 10, 1987, after a sudden illness.

Gallery divided in cornices

The authorities thought to deploy his students to complete the ceiling but decided to leave it in the incomplete state. From here onwards, the author takes the readers on a journey where she tells an in-depth story of Gallery Sadequain's cornices and paintings. Khan named each cornice according to her research and observations titled of each chapter with the name.

Before narrating the world of cornices, Khan gives an overview of the gallery just to set the tone for what's coming ahead. It was necessary to do so as everyone does not understand specific styles and icons.

It was interesting to know that Sadequain used Greek and Roman symbols because depicting religious figures is forbidden in Islam. The author explained that the decision led to a holistic work that addresses humankind. The use of iconography also carried the message to a larger audience and provided a historical backdrop to mythological legitimacy. The book unveiled that all the cornices are a mixture of Islamic, Greek and Roman traditions that avoided realistic manner to keep emphasis on the form. By this point, the readers feel like a tourist guided by the author who unwraps the intriguing universes of cornices.

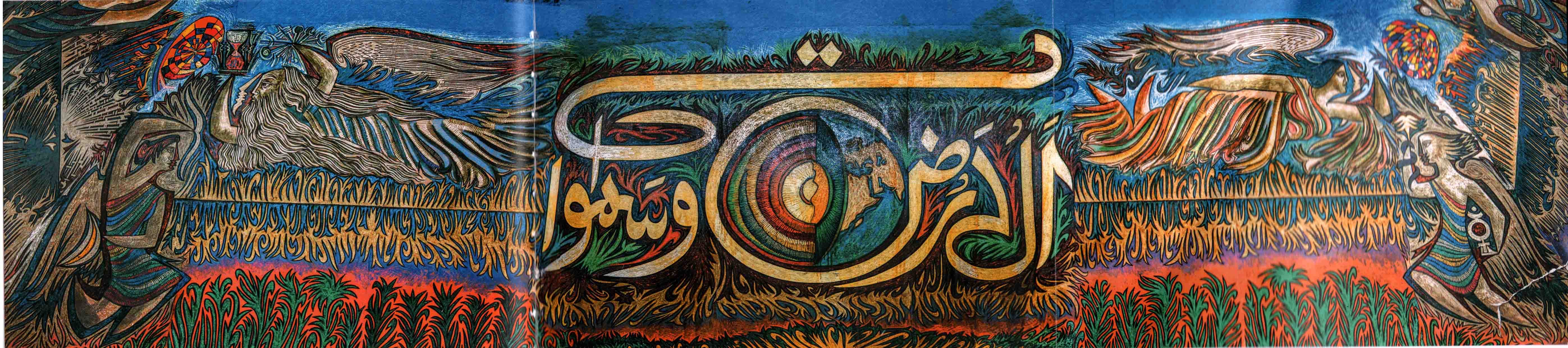

The act of creation - cornice A

From this part onwards, I started to read the book as a blank slate with no clue about art pieces. The very first description by author explains how the cornice depicts the act of creation.

The inscription alard o samawat in the middle has a globe cut in half, the circles of which show the cyclic process of creation.

But what's most captivating is the dissection of male and female figures on each side. As explained, the movement of those 'god' like figures in opposite directions symbolises the act of creation. In literature, the parent myth tells that the act of creation is splitting of primaeval entities. Following the overview in book's first half, those figures belong to Greek and Roman mythology.

To make it clearer, the author has well-defined the figures. The male resembles ‘Elohim Creating Adam’ by William Blake, and the female looks like ‘Hera, the mother goddess.’ These definitions play a vital role in building a base and developing an interest in the book and Sadequain’s work.

The chapter also explains other figures, for example, the extreme left characters are connected to earth because the presence of snakes, plants and the feminine sign shows fertility and productivity. This chapter creates curiosity among the reader and creates a curiosity about the next cornice.

The triumph of intellect in cornice B

The assessment of this particular cornice will connect with everyone who understands the importance of knowledge over worldly power.

The explanation of each figure is concise and clear. The cacti shapes and their tangled design may not make sense at first view but upon focusing it opens up as Al-Rehman. Then a reminder of time has been given with the centre hourglass. The armillary sphere symbolises the universe, while the astrolabe shapes mimic instruments used for pointing Qibla.

The most riveting explanation by the author was about the large hands. She writes that they in fact spell 'Allah,' and the smaller ones represent the efforts of man to record phenomena of the universe or solve problems of nature. Khan adds that all the figures of cornice B connect with Muses from Greek mythology and tell about history, music, poetry, songs, dance, astronomy, and tragedy.

She concludes the discussion by stating that Sadequain asserted the importance of acquiring knowledge and called it the power from which a man can conquer anything.

Struggle of opposites in cornice C

This cornice appears to be the most confusing. Even after looking from different angles with little familiarity with art pieces, I couldn't make much sense out of it. But when I read the analyses, it all made sense. Khan’s experience in the field is visible here.

In the simple choice of words, she explains that Sadequain used mythological ideas of different civilisations that focus on greater issues like creation, life after death, disasters, the power of love, the brutality of men, and the rights of society. The discussion moves forward with the study of Urdu words: noor, zulmat, aman, jang.

Apparently, the word jang, shaped like a Greek figure Typhoon (father of all monsters), is holding a spear and dagger with a crow on his head. Meanwhile, the aman holds pens, brushes, and dove with olive. The scene of pen and brush breaking the spear and dagger tells that love and peace conquers evil spirit.

With a similar approach, the remaining words were explained. Zulmat is a combination of a bat a serpent with an owl on the head and a lock in paws. Meanwhile, noor is a delicate body with a torch in one hand and a key in the other. Hence, as well written by the author, Sadequain says that only knowledge can open locks of darkness.

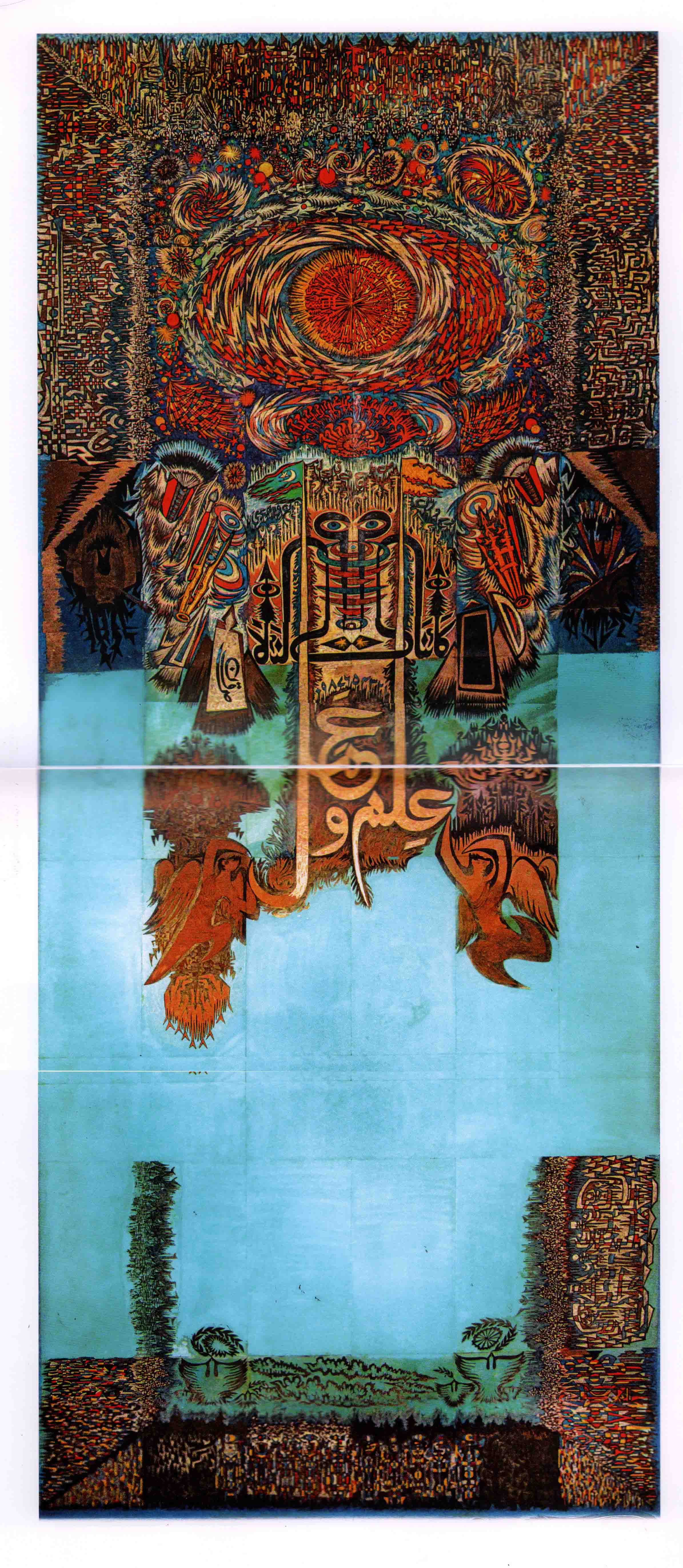

Illustration of social stagnation in cornice D and the incomplete dream in centre

At almost the end of this book, there is a deep motivation to explore more and know more about the gallery. However, this part, which almost concludes the discussion leaves the reader sad that the gallery could not be completed.

Discussing the clock in the middle with anticlockwise numbering, Khan points out that there could be more than one meaning, and one of it can be that the time is going towards detrition — a reference to social stagnation. The chapter continues by stating that the hands in the cornice resemble 'Allah,' which means that humans have a responsibility to understand the greatness of Allah.

This part of the book explains that the bodies looking upward show intellectual profoundness and those looking downwards show emotional stagnation. But the different treatment of this cornice is where Sadequain’s health began to deteriorate.

The analysis takes a turn in the middle of the ceiling as Khan’s attention shifts to the planetary objects in bold colours with the dominance of red and the words kainat and ilm o amal. According to her, the inspiration for the style came from the poetry of Allama Iqbal and it was not the first time that Sadequain attempted this style. However, before Sadequain could say anything more, the great artist had to leave the gallery incomplete. The touchups were done after his death.

The centre of the gallery

Additional chapters at the end talk about the technical aspect of Sadequain's work. These are excellent for art students to have an in-depth analysis of strokes and instruments used in the work of ceiling.

As I closed the last page of the book, I tried to think about how many times have art professors discussed the work of the homegrown maestro. In my experience, very few times indeed. There were talks about Picasso, Vincent van Gogh, Leonardo da Vinci and others, but not about the treasure in our homeland.

Why write on Sadequain?

It's not that we should never talk about masters of art such as Picasso and van Gogh, but why do we never bother to take a good look at what we have around us?

Khan shared her story and reason for analysing the Gallery Sadequain. She has been associated with the teaching profession for the last 30 years and serves as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Visual Studies at the University of Karachi.

Khan recalled her transition from being uninspired by Sadequain to becoming his admirer.

"Honestly, Sadequain's art had never inspired me previously,” Khan bluntly alludes. “His art was just an art form for me that I could categorise as stylised, abstract, deformed and exaggerated."

But during coursework for PhD, her mind started opening up, and I began to look at the subjects from different angles. “After visiting the Gallery Sadequain and working on this ceiling, my concept of Sadequain's art changed entirely. I came to know that his art is not as simple as it looks and needs in-depth study, dedication and a long time to declaim and understand the hidden meanings in his art," shares Khan.

"When I first looked at the ceiling, I used to live at Lucky Star, Saddar, Karachi. I often visited Frere Hall and saw the series of paintings on the ceiling of Gallery Sadequain. At first glance, I sensed Greek and Roman influence and perceived that these figures mesmerisingly convey some hidden meanings. Many questions prompted in my mind and it took me no time to choose this ceiling for my thesis."

And the rest is history. This book holds significance because previously no attempt has been made to formulate a book dedicated to Gallery Sadequain.

Some of the literature available on Sadequain and his work does not offer much and suggests that his art was never explored to its full extent. According to Khan, she couldn’t find a single article that explored the thematic and stylistic features of Sadequain's paintings.

Among some of the books available, is Contemporary Painting in Pakistan by Marcella Sirhandi, which discusses at length the contemporary currents in Pakistani Art. It gives the description of the lives of many important artists and classifies Sadequain under the heading of Social Commentary and Calligraphy briefly.

Sadequain Artist de Pakistan: The Missing Link by Dr Ajaz Anwar contains a series of Sadequain's works done over paper and cardboard and a formal analysis of drawings. Another book, S. Amjad Ali's Paintings of Pakistan, which covers important and upcoming artists of Pakistan has chronologically dated the major events of Sadequain's life and his important artworks.

All of these books are extremely important and hold a lot of value but cannot provide a dedicated analysis of Sadequain's artwork. This became Khan’s motivation to do an in-depth study of the thematic and stylistic aspects of the ceiling and cornices of Gallery Sadequain.

The book will art professors and students to incorporate Syed Ahmed Sadequain Naqvi in their formal education and explore his work as much as possible. This would give the great artist, an innovative painter, a poet, a calligraphist and a master muralist with his due recognition.

So much of his work, the universality of his themes, and the expressiveness of his style are yet to be examined. It is now up to the upcoming generation of artists to narrate his work to the world as Sadequain wanted to make his art accessible to the common man.

Zain Aijaz is a freelance contributor. All information and facts are the responsibility of the writer