In the days of yore, rumour mills would thrive in the absence of information from credible sources but in this current age of social media, the enormity of fake news – the most salient kind of disinformation –has grown stronger even in the presence of credible sources of information.

Indeed, the social media has changed a lot of things, particularly the way people used to live two or three decades ago. So, when it comes to journalism, we are also not immune to this change. Even the senior-most journalists, sometimes, come under the social media pressure to go after a viral fake news, much less than a budding novice, who is born and raised amid this hullabaloo.

For a reporter, like myself, success lies in listening and observing, but above all, the quality of question that will be asked to fill in the missing gaps in a story. That is called the media ethics – the ethos of journalism.

We do not have to go too far. The last year’s floods in Sindh were a major tragedy befalling upon this beautiful land. It unfolded numerous tales of tragedies, told through newspaper stories and via TV networks. But at times, the coverage of this or other disasters turned out to be the indictment of our media as far as the journalistic ethos are concerned.

Just recall, a victim, displaced by floods, enduring hunger and thirst for many days, is interviewed by a young reporter immediately upon reaching a relief camp: “How did you get here?” Or a person seriously injured in a road accident is asked during treatment, how the accident happened or a bomb blast victim is asked at the scene what was he doing when the bomb exploded.

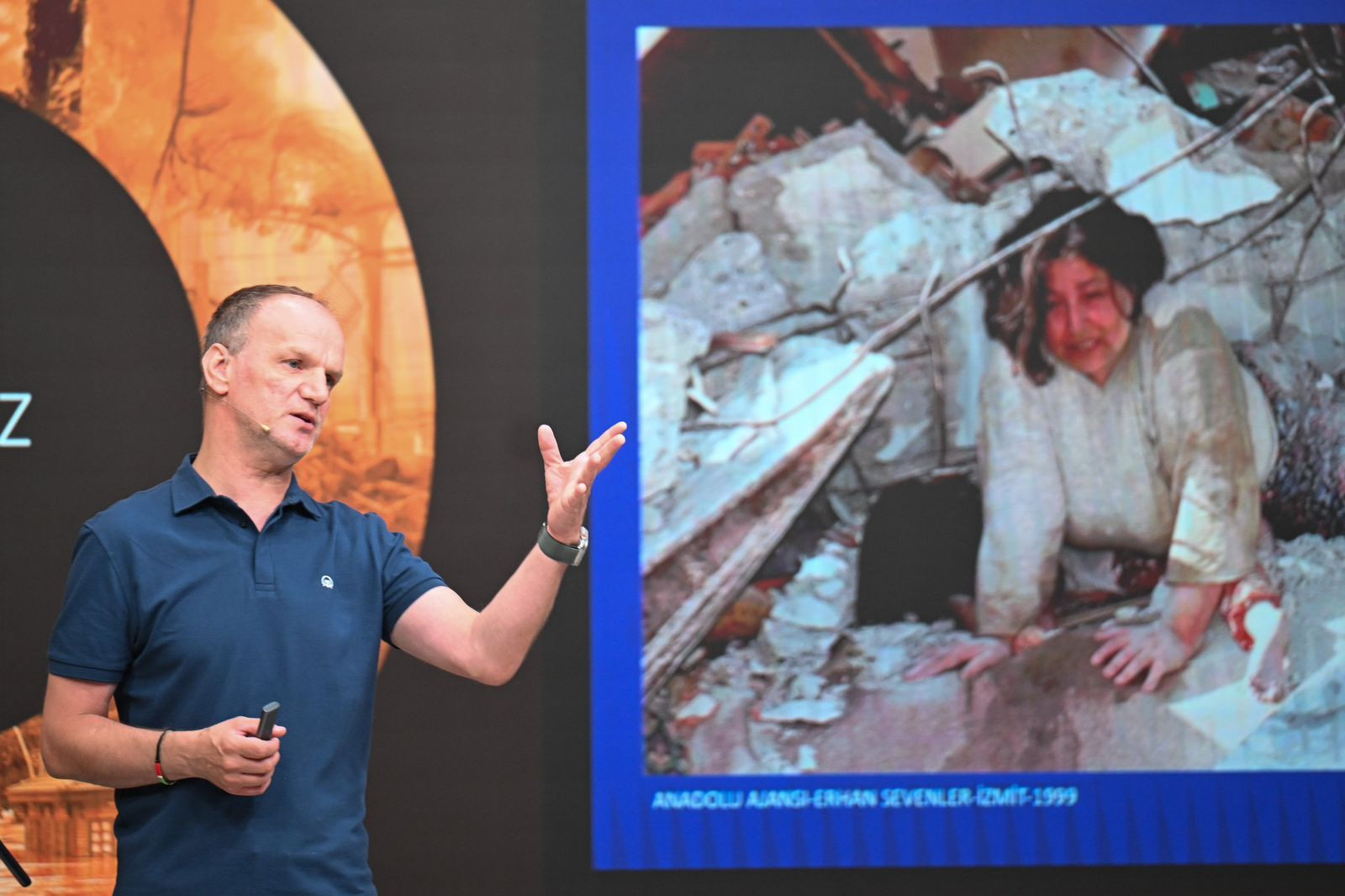

However, this is not the problem restricted to Pakistan alone. Serkan Kaya, a senior journalist in Türkiye ,had also a similar story to share during his talk with an international group of journalists at a workshop organised by the Turkish Coordination and Cooperation Agency (TIKA) in collaboration with the Anadolu News Agency in Ankara.

A woman was buried under the rubble of her residential building after the 7.7-magnitude earthquake. Without water or food for six days, she was rescued in a semi-conscious condition. When she was taken out of the rubble and put on a stretcher, her throat was aching, tongue went dry and lips were parched because of hunger and dehydration. She was in no condition to even utter a single word but all of a sudden, a reporter of a local TV channel cut through his way among the rescuers, and put his microphone to her mouth, asking: “How you spend these 6 days?”

Imparting journalistic ethics is very important for every journalist, especially those covering disasters, Kaya emphasised. “If the reporter had been taught about news ethics – journalistic ethics – he probably would not have asked any such questions from that woman in such a situation,” Kaya told the journalists from more than a dozen countries – from Pakistan to Eastern Europe to South Africa.

In the time of calamities, rescuers and disaster management authorities often encounter these situations. But they had to deal more vigorously with the fake news syndrome, that has gripped our society. According to Deloitte's latest Digital Media Trends Study, fake news has become a major problem in America. The University of Virginia has also identified fake news as a major problem. Anadolu News Academy Director Cihangir İşbilir described fake news as an “additional scourge”.

Huseyin Yilmaz, the editor-in-chief of the Anadolu Agency, explained how the fake news could have disastrous consequences. He mentioned a fake news on social media after the February 6, 2023 earthquake about the collapse of dam in Hatay. “Because of this false news, not only the ordinary citizens in the earthquake-affected Hatay panicked, but even the rescue workers stopped working and left the place,” he said.

During the course of discussion, it also transpired that though social media remains the breeding ground for fake news, sometime traditional media organisations are also forced to run such news, without checking online platforms, such as Google fact check tools, politifact, factcheck.org, snopez, FactCheck, NPR FactCheck, FactCheck Tricky, Saklica and many others.

In Turkiye, also during the earthquake rescue days, the video of the killing of a cat went viral on social media. It was claimed that the perpetrator was a Pakistani. “Everyone was talking about it and condemning it,” Anadolu News Agency Editor Ersin Altınsoy said. “So, we sent a team of reporters to verify it. When our team investigated the matter, the person who killed the cat turned out to be a Turkish citizen, who was mentally unstable and was on medication.”

Social media is a monster, having no rules or ethics. With the genre of fake news, social media has become a global franchise for anti-government people to impose their agendas. Social media also pits people against the traditional media, because they create an impression that traditional media does not carry such news. People need to understand that.

The most important aspect of this problem is how to make the people educate enough to discern between news and fake news. The government has only one tool at hand to handle any problems – legislation. But again, questions are raised when law hinders the free flow of authentic information.

In Pakistan Internet filtering is regulated by the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA) and the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) under the directions of the government, the Supreme Court of Pakistan, and the Ministry of Information Technology (MoIT). Recently, the government has introduced E-Safety Authority Bill. However, opinion has always remained divided about the efficacy and the bona fides of these laws, though everybody wants to put this genie of fake news back into the bottle.

However, journalists in several other countries, even the European ones, also grapple with a similar dilemma. “Now there is a big debate [in Croatia] because the government decided to finance several new organisations as fact-checkers, but some of them are ideologically biased [extreme right],” stated Barbara Strbac, a journalist from Croatia. “The government is also preparing a new media law in an attempt to fight fake news better,” she continued.

Strbac emphasised a point that there was a fine line between regulating fake news and ensuring journalistic freedom that must not be crossed. Elaborating on the controversial clauses of the new law, she pointed out that “they want to pressure journalists to unveil their sources if authority asks for it”. Among other things, she went on, “they want to implement a register of professional journalists, which is something that journalist union strongly protests against”.

Jayed-Leigh Paulse, a seasoned journalist from South Africa, has a different take on the subject. She said that the journalists in her country take the fake news issue very seriously but often such stories slipped through all the self-imposed regulations. “We've had several journalists writing fake stories,” Paulse said. “Most recent was a journalist –a prominent one here in South Africa – wrote about a woman who had given birth to 10 babies! It turned out to be fake.”

However, she added that the matter went as far as the South African National Editors Forum, which “issued a statement, lambasting the journalist and the media organisation for publishing this fake news and not verifying the facts of this fake pregnancy”.

Strbac made a point that the bone of contention in her country was that all those regulations she had pointed out were planned for the mainstream media and not the social networks. Paulse, on the other hand, believed that “it is essential and imperative that organisations and media houses make sure that they do their fact checking”.

Coming back to the media ethics, Paulse said: “We [have to] make sure that we have verified every single angle of that story, making sure that we've got all our facts in order.” She added: “Fake news is quite rife. It is very important that we sift fact from fiction, particularly on Twitter and on social media, where we see a lot of fake news being publicised.”

Shaikh Israr is a Karachi-based journalist who recently attended a workshop on ‘Disaster Journalism’ in Ankara, Turkiye. All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the author.