With half the world experiencing water scarcity for at least part of the year, the huge dams being built by some countries to boost their power supplies while their neighbours go parched are a growing source of potential conflict.

Ahead of a UN conference in New York on global access to water, AFP looks at five mega-projects with very different consequences, depending on whether you live upstream or downstream.

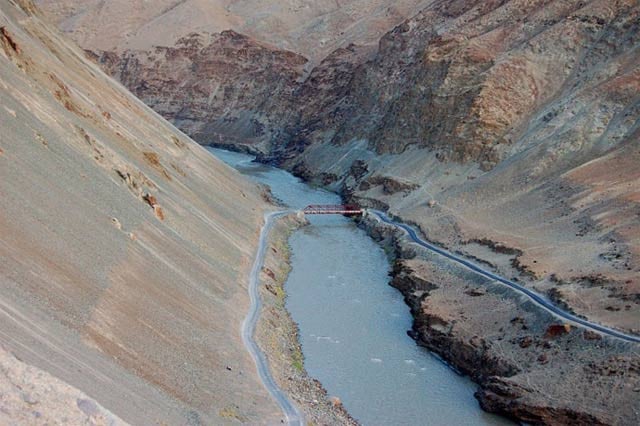

The Indus River is one of the longest on the Asian continent, cutting through ultra-sensitive borders in the region, including the demarcation between nuclear-armed India and Pakistan in Kashmir.

The 1960 Indus Water Treaty theoretically shares out water between the two countries but has been fraught with disputes.

Pakistan has long feared that India, which sits upstream, could restrict its access, adversely affecting its agriculture. And India has threatened to do so on occasion.

In a sign of the tensions, the arch-rivals have built duelling power plants along the banks of the Kishanganga River, which flows into an Indus tributary.

The waters of Africa's longest river, the Nile, are at the centre of a decade-long dispute between Ethiopia — where the Nile's biggest tributary, the Blue Nile, rises — and its downstream neighbours Sudan and Egypt.

In 2011, Addis Ababa launched a $4.2 billion hydroelectric project on the river, which it sees as essential to lighting up rural Ethiopia.

Sudan and Egypt, however, see the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam as a threat to their water supplies — Egypt alone relies on the Nile for about 97 per cent of its irrigation and drinking water.

Ethiopia has insisted the dam will not disturb the flow of water and turned on the first turbine in February 2020.

Long used to drilling for oil, war-scarred Iraq is now digging ever deeper for water as a frenzy of dam-building, mainly in Turkey, sucks water out of the region's two great rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates.

Turkey launched the construction of a gigantic complex of dams and hydroelectric plants across the southeast in the 1980s.

In 1990 it completed the huge Ataturk Dam on the Euphrates River, just 80 kilometres (50 miles) from Syria's border.

More recently, in 2019, the ancient town of Hasankeyf on the Tigris was submerged to make way for the massive Ilisu Dam.

Iraq and Syria say Turkey's dam-building has resulted in a drastic reduction of the water flowing through their lands.

Baghdad regularly asks Ankara to release more water to counter drought, but Turkey's ambassador to Iraq, Ali Riza Guney, ruffled feathers last July when he said, "water is largely wasted in Iraq".

Syria's Kurds meanwhile have accused their arch-foe Turkey of weaponising the Euphrates, accusing it of deliberately holding back water to spark a drought, which Ankara denies.

China is a frenetic dam builder, constructing 50,000 dams in the Yangtze basin in the past 70 years — including the infamous Three Gorges.

But it is China's projects on the Mekong River, which rises in China and twists south through Thailand, Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia and Vietnam, that most alarm its neighbours.

The Mekong feeds more than 60 million people through its basin and tributaries.

Washington has blamed China's actions for causing severe droughts in Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam.

In 2019, the US monitor Eyes on Earth published satellite imagery showing the dams in China holding "above-average natural flow".

Beijing insists its reservoirs help to maintain the stability of the river, by storing water in the rainy season and releasing it in the dry season.

The Itaipu hydroelectric plant, situated on the Parana River on the Brazil-Paraguay border, has often been the source of tensions between the two co-owner nations.

One of the two hydroelectricity plants that produce the most power in the world, alongside China's Three Gorges, had its energy shared out under a 1973 treaty.

But Paraguay demanded more and eventually got three times more money from Brazil, which uses 85 per cent of the electricity produced.

In 2019, a new deal on the sale of power from Itaipu nearly brought down Paraguay's government, with experts arguing it would reduce Paraguay's access to cheap power.

The two countries promptly cancelled the deal.

1719660634-1/BeFunky-collage-nicole-(1)1719660634-1-165x106.webp)

1732276540-0/kim-(10)1732276540-0-165x106.webp)

1732273396-0/Copy-of-Untitled-(72)1732273396-0-270x192.webp)

1732269802-0/Copy-of-Untitled-(71)1732269802-0-270x192.webp)

1732261957-1/Copy-of-Untitled-(66)1732261957-1-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ