Tensions rising over Indus Waters Treaty

Could focus on climate ease water woes between Pakistan and India?

As climate change impacts strengthen and water security becomes a growing concern in both Pakistan and India, New Delhi has proposed renegotiating a six-decade-old water sharing treaty - a move Islamabad so far opposes.

But renegotiation -- or at least tweaking the treaty -- may be as important for Pakistan as India, environmental experts say, as a dam-building push in both countries, rising water demand from growing populations and faster swings between drought and floods make water rights and access an ever-bigger worry.

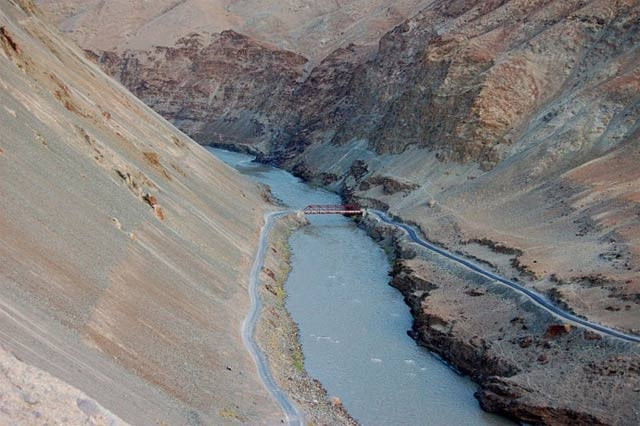

The 1960 Indus Waters Treaty - mediated by the World Bank - splits the Indus River and its tributaries between the South Asian neighbours and regulates the sharing of water. The treaty has withstood standoffs, skirmishes and even wars, but diplomatic relations between the two foes have been reduced since 2019 due to tensions over the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir, and a feud over water sharing and supplies is now intensifying.

While each country has dozens of hydropower projects in the Indus Basin currently operational or under construction, the ongoing water dispute centers around Pakistan's opposition to India's 330 megawatt (MW) Kishanganga project on the Jhelum river and the 850 MW Ratle project on the Chenab river.

Pakistan is seeking resolution at the Court of Arbitration in The Hague over its concerns with the two projects, while India has asked its neighbour to enter into bilateral negotiations to modify the Indus Waters Treaty, to stop third parties intervening in disputes.

Under the current terms of the treaty, the two countries can resolve disputes either through a neutral expert appointed by the World Bank, or at the Court of Arbitration. Pakistan has taken the latter route because it is concerned that some of India's planned and commissioned hydropower dam will reduce flows that feed at least 80% of its irrigated agriculture.

India, however, says that the way it is designing and constructing the hydroelectric plants is permitted under the terms of the treaty.

Analysts on both sides of the border say Pakistan is unlikely to reopen the agreement with India bilaterally because, as the smaller nation, it believes the involvement of international institutions strengths its position.

Yet some academics think the agreement should be reviewed to factor in climate change impacts for the first time. For example, Daanish Mustafa, a professor of critical geography at King's College London, said that doing so could ultimately benefit Pakistan, as India would be expected to take warming impacts into consideration when designing hydropower projects and making decisions about water.

A 2019 study in the journal Nature by Pakistani and Italian researchers noted that climate change was "quickly eroding trust" between the two nations and that the treaty "lacks guidelines ... (on) issues related to climate change and basin sustainability".

However, Ali Tauqeer Sheikh, an environmental and development analyst based in Islamabad, said increasingly worrying climate change pressures are currently "the best instrument available for ensuring water cooperation and regional stability".

Rather than "playing as victims of climate change", the two nations should work together to create policies that work for both, he said, adding that the treaty should be updated to cover climate-related concerns from melting glaciers to more intense rainfall.

Last month, proceedings Pakistan had sought to resolve the disagreements over water started at the Court of Arbitration. Pakistan is concerned about two Indian hydropower projects that it says will affect water flows on the Jhelum river and one of its tributaries, and water storage on the Chenab river.

India has boycotted the case, having previously suggested appointing a neutral expert while blaming Pakistan for dragging out the complaints process. Just two days before the proceedings in The Hague began, New Delhi sent a notice to Islamabad asking it to agree to modify the Indus Waters Treaty within 90 days to guarantee that disputes would be handled between the two nations without any outside interference.

Neither nation can pull out of the treaty unilaterally as there is no exit clause, according to Sheikh, who said the countries "must agree over practical solutions".

Pakistan's Institute of Policy Studies said in 2017 that the Indus Waters Treaty now needs to be considered in light of other international agreements such as the 2015 Paris Agreement to limit global warming, which Pakistan and India have both signed.

"There is very little in the treaty for the best possible use of the water resources of the river system, especially when we are in an era of climate change," said Ashok Swain, a professor at Sweden's Uppsala University and UN cultural agency UNESCO's chair of international water cooperation.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ