The TTP terror redux is here. But shall we call it a redux? Did the TTP ever call off its terror campaign in Pakistan? No, it did not. A ceasefire it publicly tore up in November had already been violated countless times by the group since its announcement in June 2022. The government wouldn’t say it publicly, perhaps to maintain an illusion of peace in the country. The ceasefire collapse, or its formal announcement by the TTP – to put it correctly – was the final nail in the coffin for the latest peace initiative brokered by Afghanistan’s new Taliban rulers. It wasn’t the first time the government engaged the TTP in negotiations. It had tried multiple times in the past, but every time the result was the same.

What’s wrong with our counter-TTP strategy?

In one word: ambivalence.

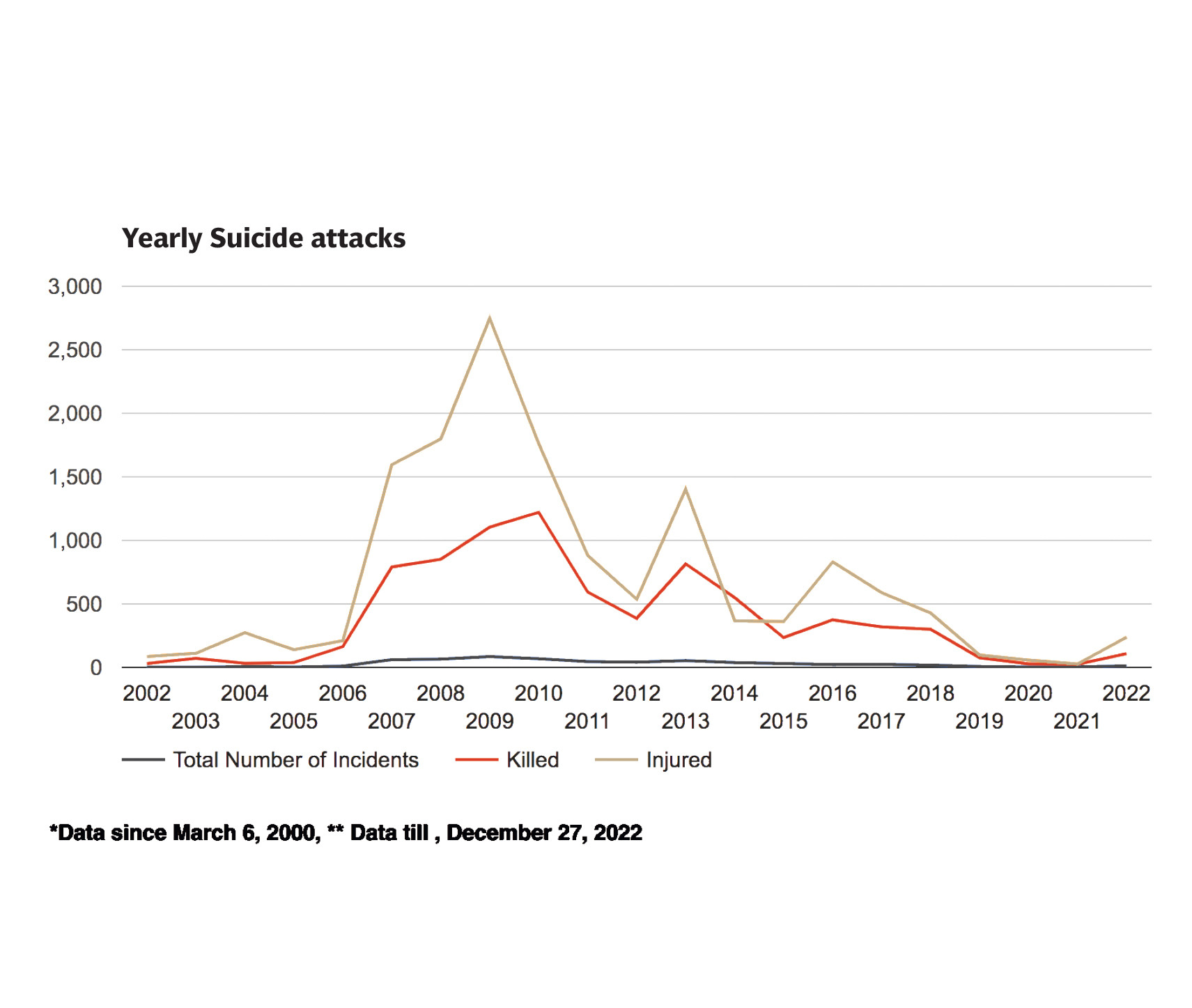

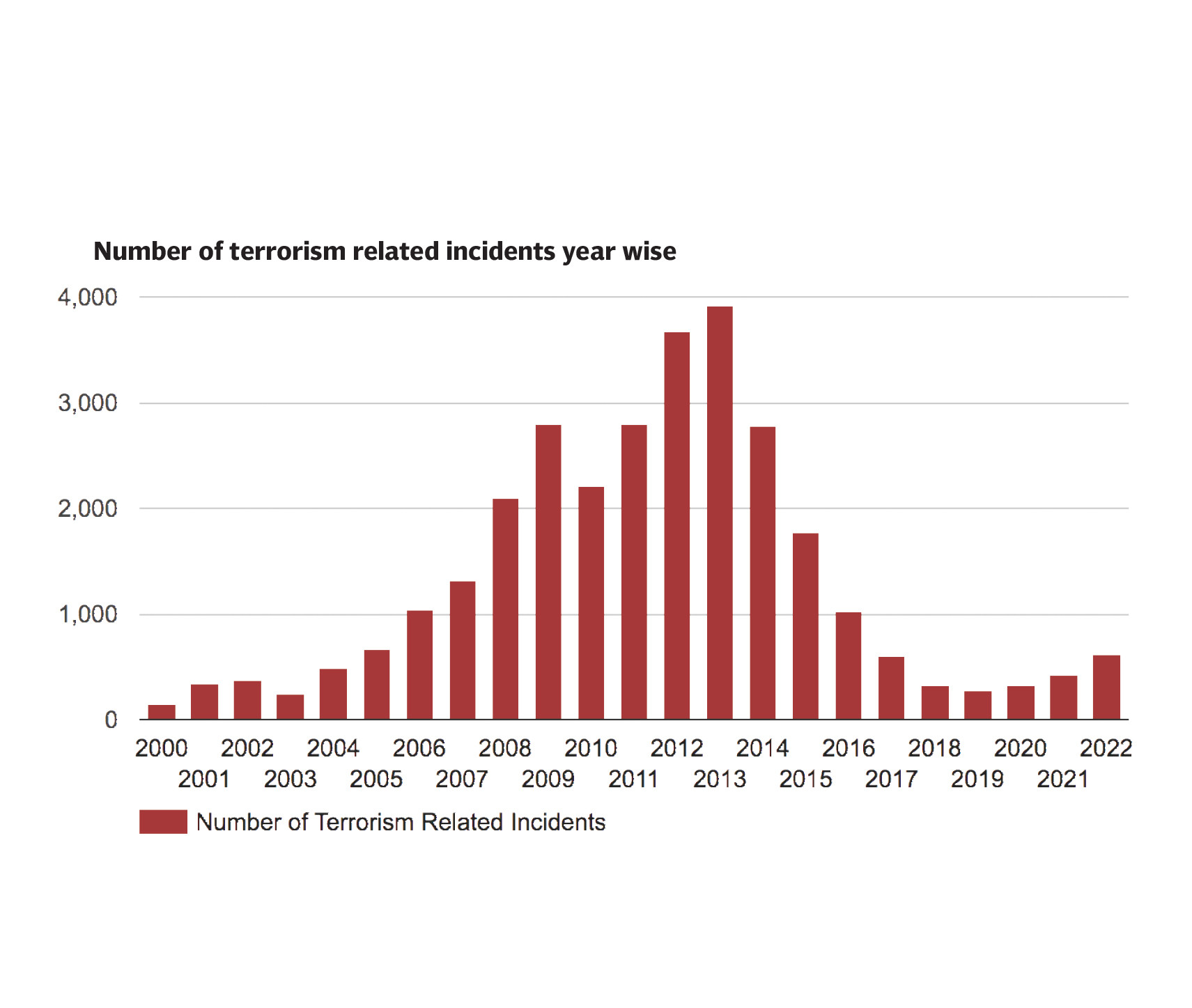

The government approach vacillated between appeasement and use of force until December 2014 when the TTP carried out the most sickening attack in its bloody campaign at Army Public School in Peshawar. This was the decisive moment in Pakistan’s battle against homegrown terror. It united the nation against the TTP. All political parties sat together to produce what is now known as National Action Plan (NAP), a 20-point comprehensive strategy to eliminate terrorism. Operation Zarb-e-Azb, which was already underway in the Waziristan region, was expedited and expanded to other areas along the Afghan border to destroy TTP’s de facto rule there. An in-sync nationwide effort was also initiated to deoxygenate religious extremists’ narrative by introducing a set of policy reforms. The aim was concrete, verifiable, and irreversible gains against terrorism and violent extremism. Monitoring committees were formed at the federal and provincial levels to oversee NAP’s implementation. The subsequent Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad tried to eliminate the “residual/latent threat of terrorism” and consolidate the gains made in the earlier military operations.

The military’s kinetic operations were a success. Beaten, battered, and bruised, but not broken, the TTP and its affiliates fled across the border into Afghanistan to recuperate and regroup in safe havens there.

The NAP started napping and our priorities shifted elsewhere as the TTP violence ebbed.

The TTP was officially branded as the biggest threat to the state of Pakistan, but paradoxically, its mother-ship in Afghanistan was treated as a “strategic asset” for the achievement of foreign policy objectives in a fissiparous country notorious for its fluid political loyalties. To expect anything good from the Afghan Taliban, the source of TTP’s inspiration, simply defied explanation, but our strategists were blinded by their obsession with India’s growing influence on the West-backed Afghan rulers.

On August 18, 2021, the Pakistani strategists made no secret of their glee when an Indian military plane, carrying the country’s diplomats, took off from an Afghan air base, temporarily ending Delhi’s diplomatic presence in Afghanistan which officials in Islamabad frequently blamed for stoking terrorism in Pakistan.

The Taliban’s rapid victory march, the dramatic escape of President Ashraf Ghani, the chaotic exit of foreign forces, and the fall of Kabul were touted as a success of our Afghan strategy. And to prove it, Pakistan’s then spy chief, Lt Gen (retd) Faiz Hameed, made a euphoric dash to Kabul to reassure a disconcerted world, “Don’t worry, everything will be okay,” and then prime minister, Imran Khan, praised the Afghans for “breaking the shackles of slavery".

The euphoria proved short-lived.

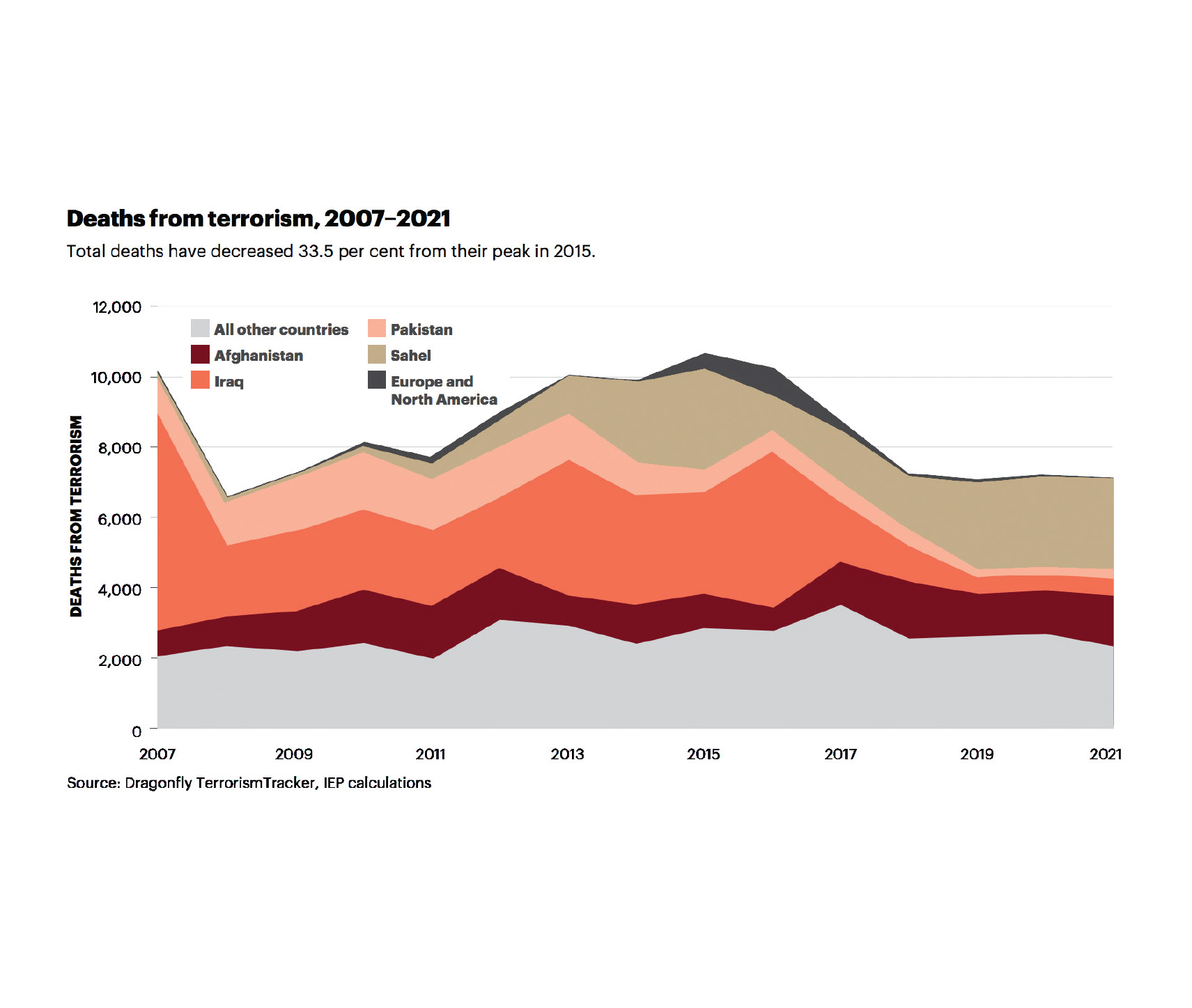

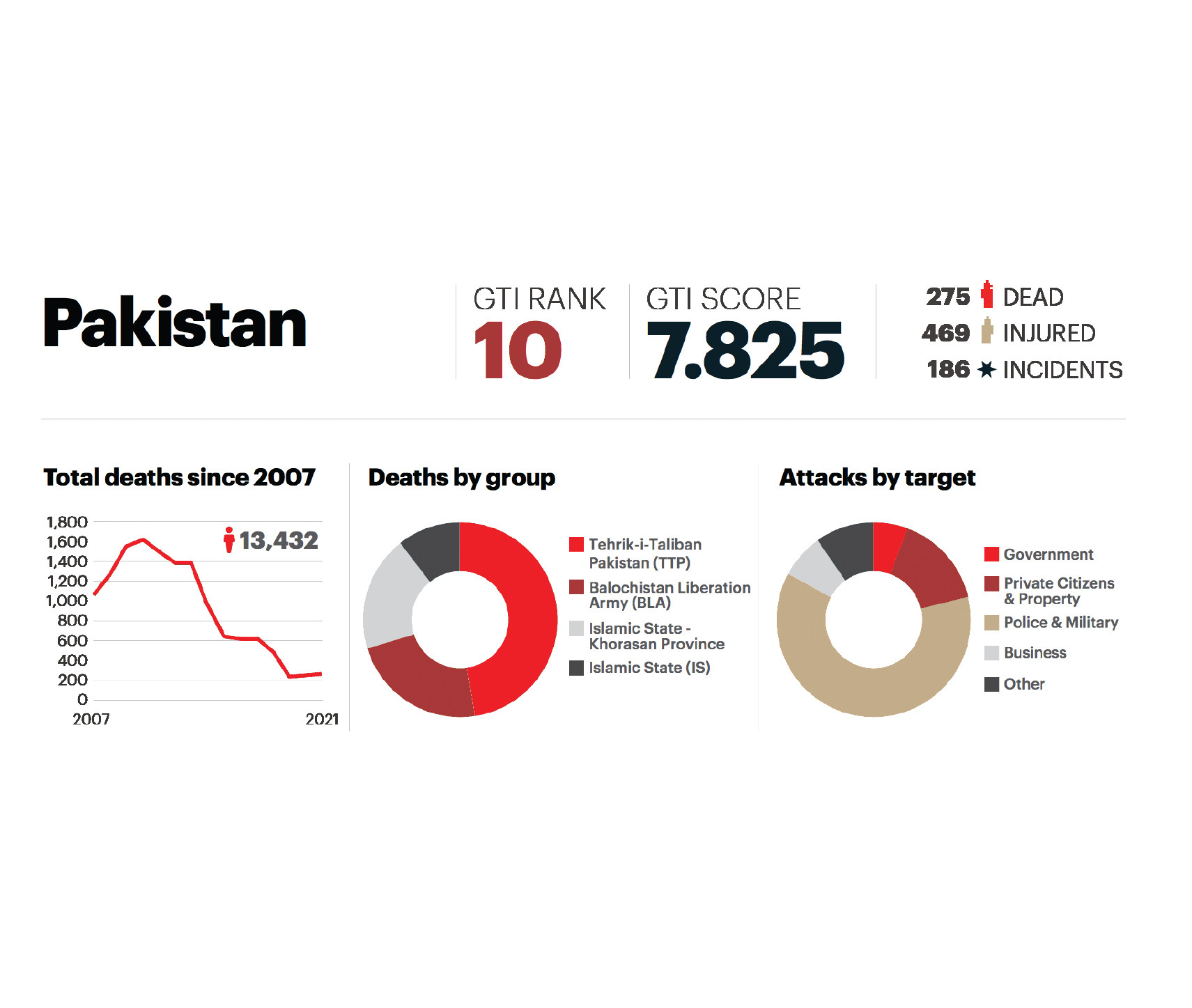

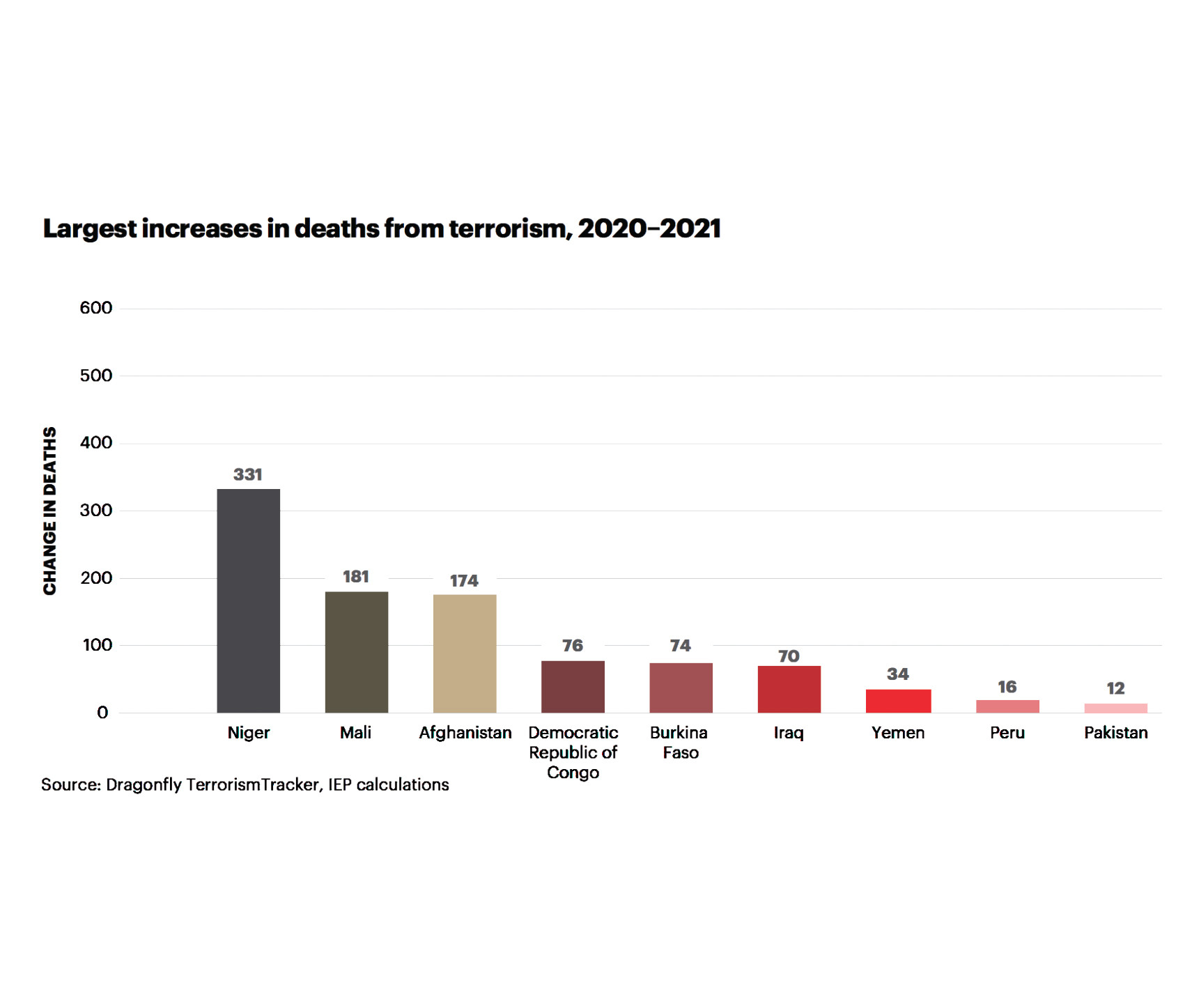

Dozens of TTP commanders and fighters were released from Afghan prisons after the fall of Kabul. The Taliban victory rejuvenated the TTP and offered it greater operational freedom in Afghanistan. An upsurge in TTP attacks followed. Unofficial data show a 51% increase in terrorist violence between August 15, 2021, and August 14, 2022. At least 433 people were killed and 719 injured in 250 attacks across Pakistan, according to a tally maintained by the Pakistan Institute of Peace Studies. There were 165 attacks that killed 294 people and injured 598 from August 2020 to August 14, 2021.

Pakistani officials were surprisingly unperturbed. At the time, a top security official tried to downplay the uptick in the TTP attacks during a background briefing. He was convinced that the wave of TTP terror would subside within “four to five months” after the new Afghan rulers managed to establish their writ.

The Taliban regime remained non-committal on a crackdown on the TTP despite repeated calls from Pakistani officials. Instead, Sirajuddin Haqqani, the interior minister in the interim Taliban regime, offered to broker peace negotiations between the two sides. Pakistan accepted the offer despite bitter experiences of the past when the group used negotiations as a ruse to regroup and re-energise. Lt Gen (retd) Faiz Hameed, then corps commander Peshawar, oversaw the negotiations, which also involved Pakistani tribal elders. It was a bad idea to have direct talks with the TTP because a state actor was obliged to sit across the table with a non-state armed group, lending it legitimacy. Months of behind-the-scenes negotiations hosted by Haqqani pulled a breakthrough in June. Sources privy to the talks say too much was conceded to the TTP in return for a shaky ceasefire risking the country’s antiterrorism gains, just because the overseer wanted to have another feather in his cap.

Subsequently, TTP fighters reemerged in border regions of Pakistan, particularly in Swat, to test the water. The common perception was that the TTP’s return had the tacit approval of the authorities. Targeted attacks on tribal elders and politicians, extortion, and even kidnapping of security officials started as the TTP sought to stage a comeback. However, local residents rose up against the return of the TTP scourge. Massive protests were staged in major cities of Swat, saying no to efforts to reestablish the regressive group as a legitimate part of the region which it once subjected to a reign of terror.

A month after the truce, al Qaeda chief Aymen Al-Zawahiri was killed in a US drone strike in an exclusive Kabul neighbourhood. Taliban’s defence minister Mullah Yaqoob pointed a finger at Pakistan, laying bare tensions between the two neighbours. “According to our information the drones are entering through Pakistan to Afghanistan, they use Pakistan’s airspace, we ask Pakistan, don’t use your airspace against us,” Yaqoob told a news conference. Islamabad denied the charge. The friction led to an unannounced end to the Haqqani-brokered peace initiative as the Taliban sought to leverage their influence over the TTP to put pressure on Pakistan over the Zawahiri strike.

Towards the end of August, five TTP senior commanders, including the group’s founding member Abdul Wali, alias Omar Khalid Khorasani, and intelligence chief Abdul Rashid, alias Uqabi Bajauri, were killed in targeted attacks in Afghanistan. The TTP blamed Pakistan’s security agencies and resumed sporadic attacks on the pretext of “retaliation” without publicly scrapping the ceasefire. By its own admission, the group carried out nearly 60 attacks in November alone.

The peace initiative was rendered as good as dead, especially after the transfer of Faiz Hameed and the preoccupation of Haqqani with a resurgent IS-Khorasan. Frustrated by the deadlock on its key demands, the TTP publicly ended the ceasefire and timed it with a top Pakistani delegation’s visit to Kabul towards the end of November. A fresh wave of attacks has followed, triggering talk of another military operation. “The situation in parts of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, particularly in the tribal districts, has deteriorated to the extent that a major military offensive cannot be ruled out,” an official said in December.

So, we are back to square one.

The National Counter-Terrorism Authority (Nacta) said in a recent report that the TTP used the peace process to regroup and reorganize. “The TTP, during the peace process, gained considerable ground; increased its footprint and magnitude of activities,” it stated. “The withdrawal of the US forces from Afghanistan gave impetus to TTP activities with its base [still] intact in Afghanistan.” Ironically, nobody is willing to take ownership of the moribund peace initiative. The incumbent coalition government blames its predecessor, especially Imran Khan, for starting “negotiations with those who martyred our schoolchildren at APS”. But Interior Minister Rana Sanaullah said in June that the parliament had authorized the military to hold talks with the TTP. A day later, a senior politician of a government ally disputed Sanaullah’s claim saying that the military had briefed a parliamentary panel on talks that were already underway. “No permission was sought by the military from parliament for holding talks with the TTP,” PPP’s Raza Rabbani said.

Is a negotiated settlement possible?

Probably not.

The group’s core demands are akin to the state’s capitulation. Its refusal to disarm and disband and its insistence on the reversal of ex-FATA’s merger with K-P snitch on its sinister plans to establish a self-styled mini “Emirate” and gradually export its regressive ideology to the rest of Pakistan. The Taliban’s victory has strengthened the TTP’s belief that it is doable, especially at a time when Pakistan is politically volatile and economically fragile. The group also knows that its fighters now enjoy de facto asylum in Afghanistan where the Taliban are firmly ensconced.

The Taliban regime has no incentives to crack down on the TTP. They would never like to alienate and antagonize their former “brothers-in-arms” which, they fear, could trigger defections to the rival IS-Khorasan, create splits within their own ranks, and endanger their ideological affinity and ethnic amity with people in Pakistan’s border regions who they have always fallen back on. An increasingly suspicious Taliban regime also knows that it can use the TTP as bargaining leverage with Pakistan. Kabul tacitly endorses TTP’s demand for the reversal of the FATA merger believing it would also address its concerns about restrictions on free movement through the Durand Line which has been fenced by the Pakistani military. The border frictions have recently escalated into deadly clashes between the security forces of the two countries – and even a diplomatic spat.

The Taliban appear to be limiting reliance on their longtime benefactor Pakistan by diversifying their international partnerships. Few senior Afghan officials have visited Islamabad since the Taliban’s ascent to power. Instead, they preferred to have diplomatic interactions with the US in Doha, Qatar. India is back in the Afghan calculus as it has accorded de facto recognition to the Taliban regime by sending diplomats to its Kabul Embassy. The US Special Representative for Afghanistan Thomas West met with former Afghan leader Abdullah Abdullah in the first week of December in New Delhi where he “greatly appreciated India’s substantial humanitarian assistance and commitment to the fundamental rights of Afghans”.

Does that mean Pakistan’s overarching goal of marginalising Indian political influence in Afghanistan has boomeranged? Apparently, yes.

What options does the government have?

Given past experiences, negotiations may be off the table. Any peace process has to have the prior endorsement of Parliament, which should weigh its pros and cons for society through a public discourse for national ownership of the process. But negotiations may not be favoured by most Pakistani civilians who have borne the brunt of TTP’s deadly terror campaign for years. They must be averse to the idea of giving the TTP amnesty for its crimes against humanity and integrating it as a legitimate actor of society.

The resumption of hostilities by the TTP has pushed the government back to the drawing board to recalibrate its strategy. There are reports that the government might be considering the use of military force to stem the tide of TTP violence. Foreign Minister Bilawal Bhutto Zardari has already dropped a broad hint.

“As far as the TTP [safe haven] is concerned, it’s absolutely our red line, it is something that we will not tolerate… we would be willing to consider each and every single option to ensure the safety and security of our own people,” he told the media on his recent visit to the US. Bilawal observed diplomatic niceties, but Interior Minister Rana Sanaullah was blunt, saying that international law allows Pakistan to carry out cross-border military action.

The United States has already offered to help Pakistan deal with a resurgent TTP and secure the border. “We are concerned by the threats posed by Tehreek-e-Taliban-Pakistan to Pakistani security and stability. During my visit to the GHQ, we discussed opportunities to address this threat,” CENTCOM commander General Michael E Kurilla said during his visit to Islamabad in Dec.

However, the nature of any “major military operation” by Pakistan is unclear because the TTP doesn’t have a visible organized presence anywhere in the erstwhile tribal belt that it once virtually ruled. And this is amply clear from the demand by TTP terrorists during the recent CTD Bannu siege for a “safe passage” into Afghanistan. TTP’s safe haven is across the border. Will the military carry out cross-border actions against TTP targets using manned or unmanned aircraft?

A cross-border military action wouldn’t be unprecedented. In April 2022, Pakistan had launched airstrikes against TTP targets in the eastern Afghan provinces of Khost and Kunar which also caused some civilian casualties. But this option would have disastrous pitfalls. It would set a dangerous precedent for other regional countries that accuse each other of harbouring terrorists. It could also damage Pakistan-Taliban relations beyond repair because the last strike had triggered a seething response from Kabul with Zabihullah Mujahid calling it “a cruelty” that would pave the “way for enmity between Afghanistan and Pakistan.” He warned that Islamabad “should know if a war starts it will not be in the interest of any side.”

Cross-border military strikes would also rejuvenate anti-Pakistan sentiments, marginalize pragmatists in the Taliban ranks, and increase support for the TTP in Afghanistan. And accepting US help for counter-TTP operations inside Afghanistan might exacerbate the Pakistan-Taliban mistrust to the point of no-return because the theocratic regime would take it as a repeat of the post-9/11 “betrayal” by Pakistan.