Pakistani security strategists might have thought the exit of foreign forces and the return of the Taliban in Afghanistan would put an end to the bloody campaign of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, a group globally designated as terrorist. This, off the record they claimed, might take a couple of months to happen. They were dead wrong. On the contrary, the Taliban’s swift victory rejuvenated the TTP as hundreds of its fighters returned to join the fight after their release from Afghan prisons. Senior TTP commanders also re-emerged from hiding to enjoy de facto political asylum under the Taliban rule. The group renewed allegiance to the Taliban spiritual leader Maulvi Hibatullah Akhundzada as it stepped up attacks in Pakistan. The fledgling Taliban theocracy, however, is non-committal about a crackdown fearing it might be seen as betrayal by the TTP and other “jihadi” groups.

At the same time, the Taliban also know that they have greatly benefited from Pakistan’s hospitality and largesse and that it is time to return the favour. Pakistani officials expect the Taliban to facilitate negotiations with the TTP, nudge the group to accept a deal, and then serve as guarantors of its success. The nascent process yielded a ceasefire late last year, which the TTP has since extended for an “indefinite period” as negotiators from both sides weigh each other’s demands. The breakthrough, if this is what the negotiators would call it, was made last month when a representative jirga of tribal elders from all erstwhile tribal regions flew to Kabul to join Pakistani security officials in direct talks with the TTP leaders.

THE GENESIS

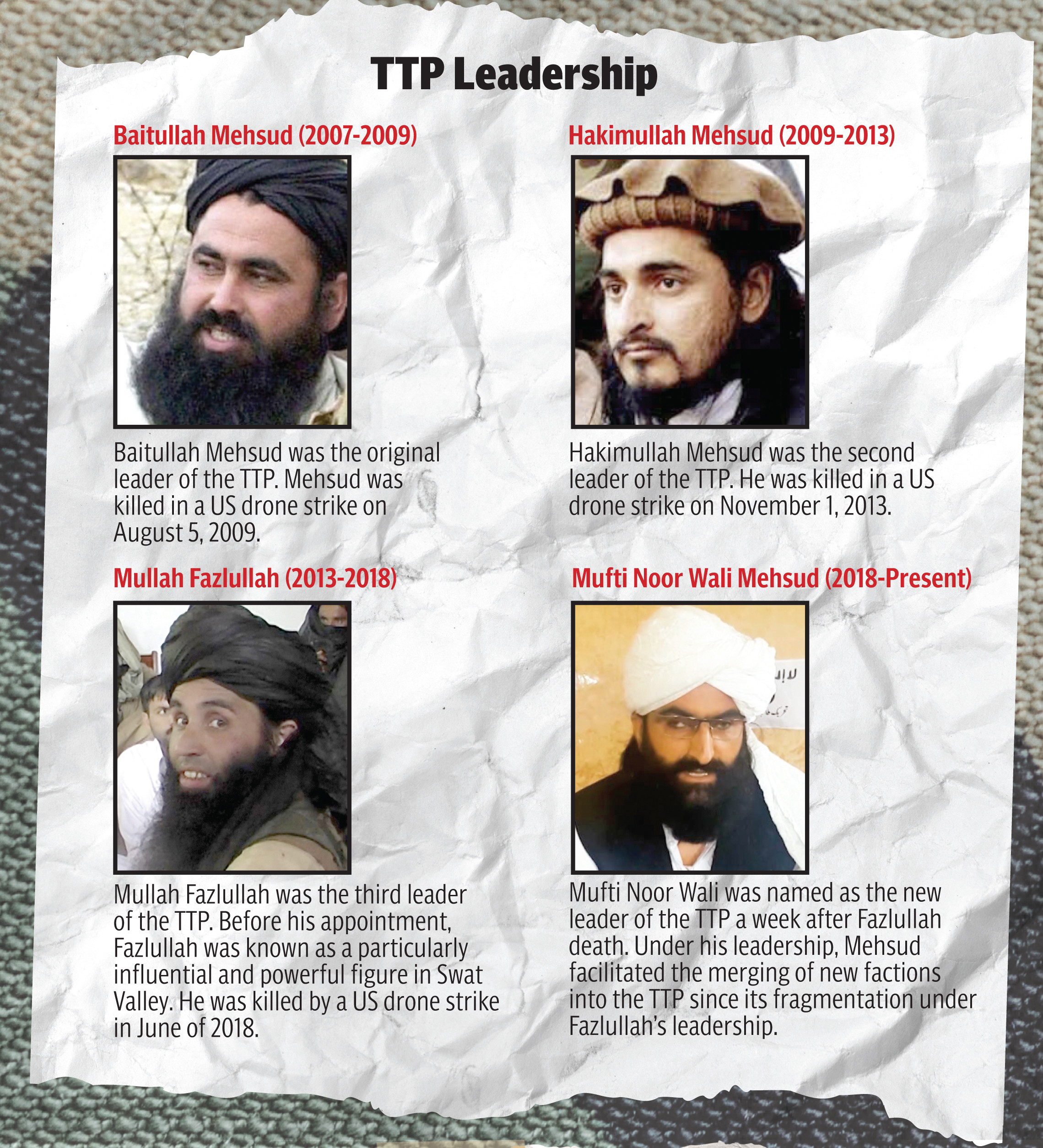

The TTP was born in Dec 2007 when more than a dozen groups coalesced under the leadership of Baitullah Mehsud mainly to join the Taliban “jihad” against the US-led coalition forces. The group lost its founding leader in 2009 when Baitullah was killed in a US drone strike in Waziristan. Hakimullah Mehsud, a young clansman of Baitullah, took up the mantle. Four years later, he was also killed in a US drone strike. This decapitation strategy of the US forces briefly worked. Mullah Fazlullah, nicknamed Mullah Radio of Swat valley, became the first non-Mehsud chief of the TTP. Not everyone was happy and some factions refuse to pledge allegiance. The group, which was weakened by centrifugal forces, suffered the devastating blow in June 2014 when it was routed by the Pakistani military in Operation Zarb-e-Azb.

Mullah Radio and his loyalists fled to Afghanistan to find safe havens there. The TTP cracks and splits deepened when Fazlullah was enlisted by the Afghan and Indian spy agencies for a “proxy war” in Pakistan. In June 2018, Fazlullah was killed, also in a US drone strike in Afghanistan.

THE NOOR WALI EFFECT

Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud, an Islamic scholar, writer and jurist, was picked to succeed him. The TTP he inherited was in a precipitous decline. He took his time to work out a plan to reconfigure the group, and remedy internal divisions for a potential comeback. Wali now epitomises the group’s reorientation with a visible ‘lessons-learnt’ approach. It is evident from his book “Inquilab-e-Mehsud”, as well as the TTP’s revised code of conduct which lays emphasis on three points:

(a) Establishment of a centralised command and governance structure – for operations, imposition of Shariah, and governance. Modeled along the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) while cognizant of how splintering of the group into pro-IS-K, pro-Afghan Taliban, and pro-NDS groups had led to its decline and loss of focus on “jihad” in the past.

(b) Clearly laid out vision, history, identity, and targets list: The goal being modeling itself as an ideologically sound political, religious and ethnic resistance group as opposed to an international terror group (lessons learnt from al Qaeda and ISIS failures against the US).

(c) Well managed external relations: Ensuring that the Pakistani state remains isolated by give up transnational Jihadism and prevent sucking other powers and actors in its fight against the state of Pakistan. The aim is to co-opt or maintain mutually beneficial arrangements with allies and rival factions, such as IS-K, IEA, and former splinter groups and tribes, via politico-strategic means.

(d) Project a finely-tuned brand image aimed at leveraging the maximum appeal for all potential recruits, by being violent enough to not alienate hardliners, and by being moderate enough to attract young educated religious-orientated youth from Tehreek-Labbaik Pakistan, Hizbul Tahrir, Jamaat-e-Islami and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, etc, as well as from more ethnic yet diverse lines such as from Central Asia, Balochistan, and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.

Wali’s efforts to rebrand, reorient, and unify the TTP met success as he started garnering pledges of allegiances. “Within two years, the TTP was reorganized by embracing Jamaatul Ahrar, Hizbul Ahrar, Amjad Farooqi Group, a faction of the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi sectarian outfit, Moosa Shaheed Karwan Group, Mohmand and Bajaur Taliban, the Lal Masjid-famed Ghazi Brigade, and Punjabi Taliban. All of them do not have the same degree of hostility towards Pakistan and its forces,” says defence analyst Maj Gen (retd) Inamul Haque.

WHY NOW?

Noor Wali – who fought alongside the Taliban against the Northern Alliance in 2001 – maintains good relations with the Haqqani Network, known as the Taliban’s military strategists. It was Mufti’s closer links with the Haqqanis that might have motivated the Pakistani agencies to reengage the TTP in negotiations. Sirajuddin Haqqani, the Taliban acting interior minister, is said to be mediating the ongoing talks.

“The current negotiations began when the Taliban’s swift takeover of Afghanistan gave Pakistan an opportunity to enlist their assistance in dealing with the TTP. Pakistan sees the Taliban as a facilitator of discussions with the TTP, as an ally in persuading the TTP to negotiate, and as a guarantor of whatever agreement is reached,” says Brian Michael Jenkins, a senior adviser to the president of the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation.

The Afghan Taliban, however, also see a quid pro quo here. “Given the Taliban’s continuing diplomatic isolation and the country’s desperate economic situation, Pakistan can in return assist Afghanistan’s new rulers in gaining acceptance and aid. Kabul’s help in ending the long-running conflict could give the Taliban credibility as a responsible regime,” says Jenkins, who has authored numerous books, reports, and articles on terrorism-related topics.

‘SOLDIERS OF FORTUNES’

TTP’s top cadres are warlords who have earned respect within the group based on fighting and operational and leadership experience along with tribal affinity. The foot soldiers are likely young tribesmen, recruited along ethno-religious, tribal and masculine ideals to fight for their identity, way of life and ideology: a rejection of not only foreign imperialism, but also so-called modernity that is in conflict with their tribal customs and identity.

The TTP had one founding goal: to join the Taliban-led “jihad” against the US-led foreign “occupation” of Afghanistan. Enforcement of Shariah law throughout Pakistan, a separate homeland, and autonomy were not among their initial demands. But since the TTP is an assemblage of factions, its commanders may differ in their prioritization of the group’s goals. “The Swat Taliban are only interested in enforcement of Shariah law in Malakand Division. The Wazir and Mehsood tribes of Waziristan are aggrieved because the government has violated their land by launching military operations in 2003-04. The Kurram and Orakzai Taliban are inspired by al Qaeda and their main objective is to have the upper hand in their fight against the Shias in Kurram. The Khyber Taliban are mostly soldiers of fortune,” says Gen Inam.

Dr Michael Barak, a senior researcher at International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT), is convinced that the TTP is a coalition of small terror groups influenced by al Qaeda’s ideology and its stance toward the near enemy. “Al Qaeda argues that Pakistan is an illegitimate state since it does not follow Sharia, collaborates with the West and oppresses its people, etc,” he says.

According to Jenkins, foot soldiers in terrorist groups are driven by diverse motivations. “They are not conscripts yearning for the fighting to end so that they can go home, but self-selecting volunteers who, often dissatisfied with their lives, seek the rewards that joining a terrorist group offers — assumed status as a “warrior,” participation in an epic struggle, an exciting life, an opportunity to pursue baser violent instincts, passage to paradise. For others in the ranks, warfare is a source of income,” he says.

This is true of the TTP, says Gen Inam. Some of them might be motivated by an ideological cause, while others are lured by money and prospects of a higher social status. At the centre is the top hierarchy, driven by a politico-religious ideology, while the mass is gullible youth, he says. “The foot soldiers are the disenfranchised and mostly uneducated youth. Joining the TTP elevates their social status. They grow beard, carry assault rifles and inspire awe and respect in their villages. And in death, they get the coveted status of martyr while the TTP takes care of their families with regular stipends.”

‘SAFE HAVENS’

The 29th report of the UN Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team assesses “the number of TTP fighters at between 3,000 and 5,500 in Afghanistan”. The report identifies the provinces of Ghazni, Helmand, Kandahar, Nimruz, Paktika and Zabul as places where the group fought alongside the Taliban against the ousted Afghan government.

As per their tribal affinity and leadership under the Mehsud tribes, the likely stronghold and ethnic/on-ground legitimacy for their ‘movement’ stems from Waziristan and the bordering Afghan provinces of Khost and Paktika. The group is also based around the mountainous Nangarhar province, skirting around Kurram tribal district. Their fluid relations with the Khorasan chapter of Islamic State (IS-K) allow them to act not only as brokers but also as enforcers for helping secure the vital smuggling routes.

The IS-K’s stronghold is known to have been around the Spin Ghar mountains near Parachinar, which following the US withdrawal and Taliban pushback against the IS-K is likely to have led to TTP managing relations between the two. The same holds true for their expanding reach around Kunar, opposite Bajaur and Mohmand tribal districts of Pakistan.

Gen Inam says the “IEA” has concentrated the TTP fighters and their families in the provinces of Nangarhar, Kunar, Khost, and Paktika. “In April, Pakistan carried out precision airstrikes in the same area (border regions of Kunar and Khost) in which the group was badly hit,” he adds.

FLOW OF FUNDS

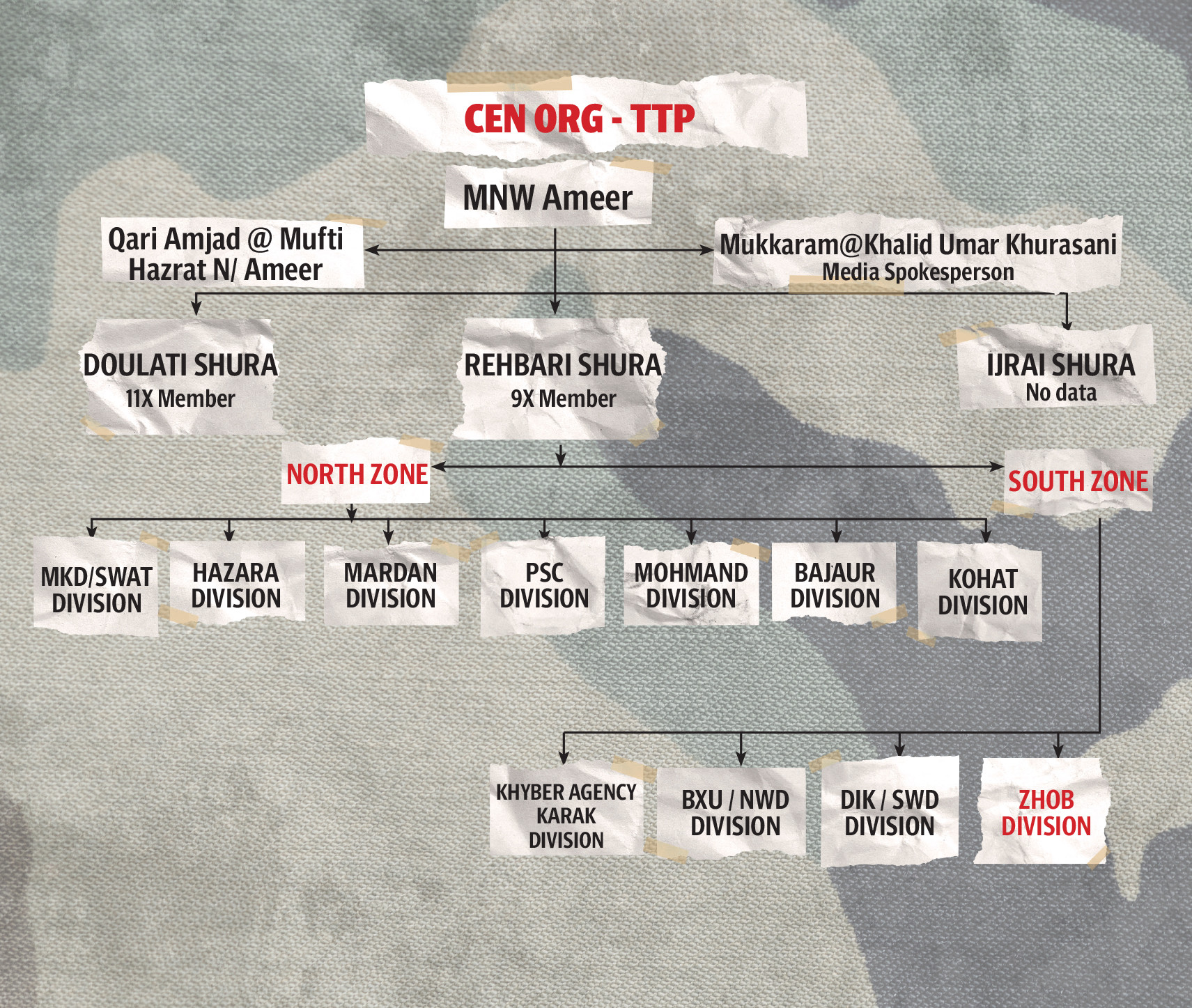

The TTP organisational structure comprises local emirs and six-member Shura councils based according to regions that are answerable to a central emir and the grand Shura council. Each franchise is responsible for sustaining its own operations, according to the 2020 UN report. Kidnapping for ransom, mining of natural resources, smuggling of drugs and guns are their primary funding sources, while extortion: transit/toll taxes are secondary and donations from al Qaeda, IS-K, etc, are tertiary sources of funds.

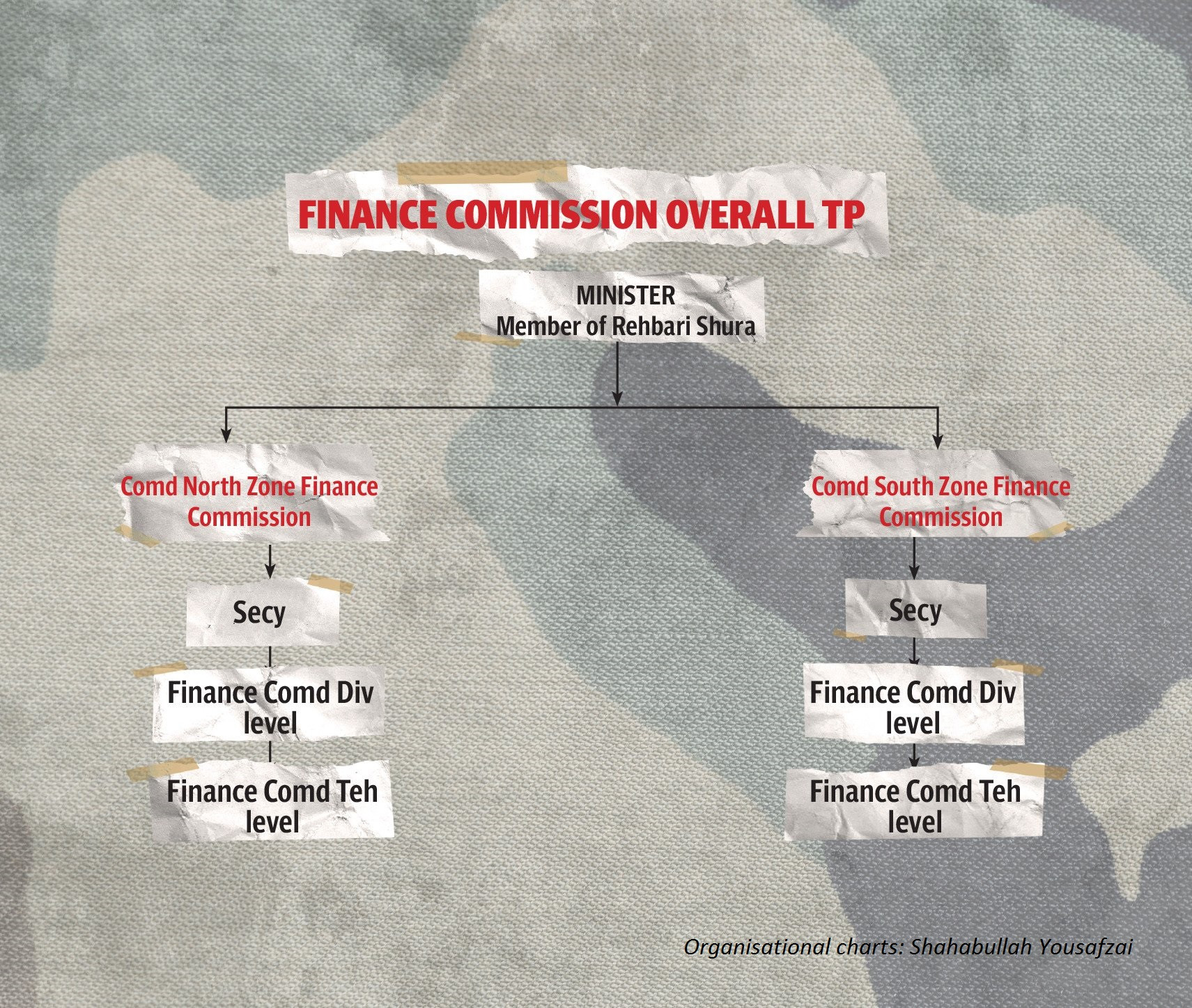

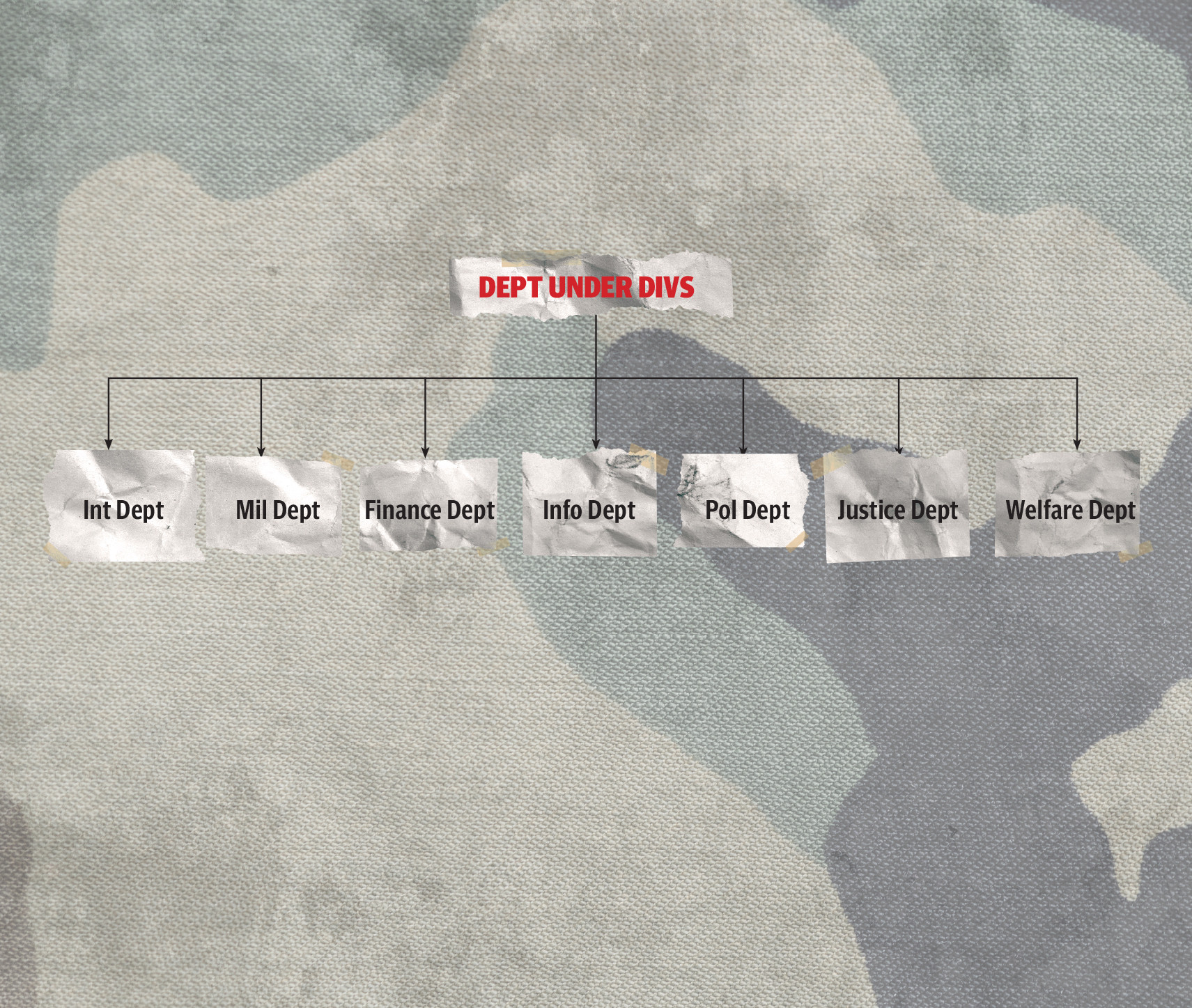

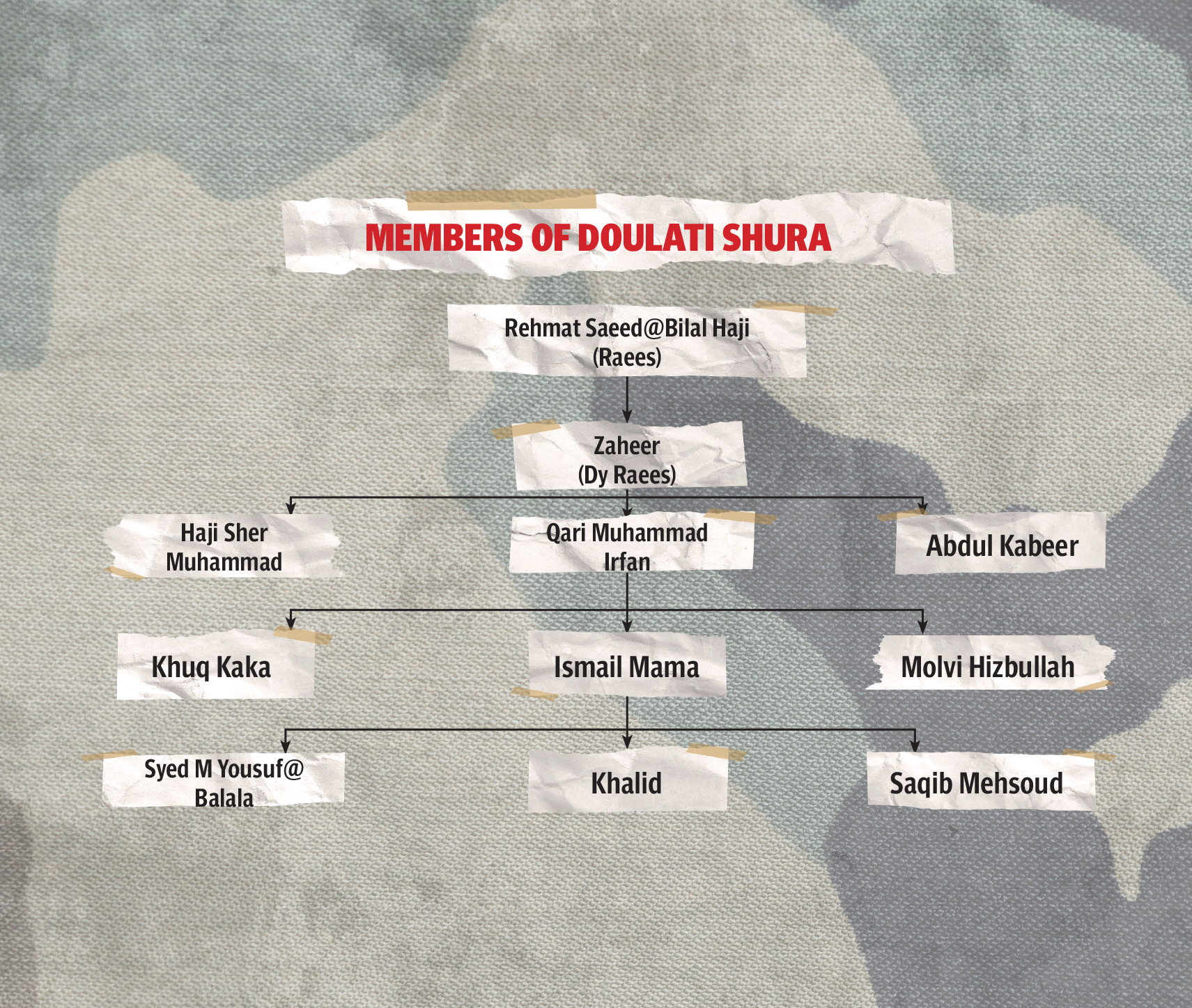

Organisational chart: Shahabullah Yousafzai

“They have three main sources of funds: kidnapping for ransom, extortion (taxes) from the areas under their control, and narcotics trade,” says Gen Inam. The group also receives donations collected in mosques in the Middle Eastern and even in some European countries.

In the past, Afghanistan’s NDS and India’s RAW also bankrolled the TTP under alleged CIA patronage. “I’m privy to some of communication intercepts between TTP commanders in which they defended taking money from an ‘infidel’ country like India for their supposed pious cause,” recalls Gen Inam, who had served in Pakistan’s border regions during his military service.

POSITION OF STRENGTH

Critics say negotiating with terrorists is akin to legitimising terrorism and incentivising violence. It becomes more perilous when you’re not sure if the group you’re negotiating with really wants to renounce violence or it is just buying time to reorganize and regroup. Dr Barak believes a group would only agree to negotiate if it has been considerably weakened. He cites the examples of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, Irish Republican Army, Gamma Islamiyya, Libyan Islamic Fighting Group and Palestine Liberation Organisation. “All these examples prove that most successful deals are achieved when the groups are found in a weak position,” he says. “It’s good to negotiate with the TTP, but at the same time, Pakistan must be very cautious about the group’s motivation.”

The TTP is not a monolith. It is a fragile coalition of smaller formations. Dr Barak believes it’s always difficult to negotiate with a fissiparous group because there is always a possibility that one of its factions will refuse to accept the deal. “But this should not discourage Pakistan from negotiating with the TTP. If there is a strong leadership in the TTP, it may force most of its members to respect the deal. Pakistan may see where the wind blows and calculate where negotiations are heading,” he adds.

QUID PRO QUO

The Taliban regime has been mired in multiple challenges since August last year which include persistent diplomatic isolation, deepening economic chaos, and a worsening humanitarian crisis.

“In this situation, the Taliban are interested in sending signals to the international community, including Pakistan, that they don’t support terrorism in order to gain international recognition for the legitimacy of their rule in Afghanistan and to attract foreign investments,” says Dr Barak. A deal between the TTP and Pakistan government would strengthen this perception.

Jenkins agrees. “Given the Taliban’s continuing diplomatic isolation and the country’s desperate economic situation, Pakistan can in return assist Afghanistan’s new rulers in gaining acceptance and aid. Kabul’s help in ending the long-running conflict could give the Taliban credibility as a responsible regime,” he says.

However, Dr Barak is not optimistic a peace deal may last long because, according to him, the TTP is not in a weak position. “That means the TTP is accepting the game’s rules dictated by the Taliban: to halt terrorist actions against Pakistan – but only for a short term,” he says.

Jenkins concurs. “The Taliban’s victory in Afghanistan boosted the morale of jihadists everywhere who view the success as confirmation that God is on their side. If jihadist resistance fighters can defeat the Soviet Union and the United States, their thinking goes, a TTP victory over Pakistan seems inevitable,” he says.

PROSPECTS OF DEAL

A Pakistan-TTP deal shouldn’t be out of question. The two sides have signed several agreements in the past, beginning with the Shakai accord in 2004, Sararogha accord in 2005, Waziristan accord in 2006, and the Nizam-e-Adl agreement in 2009. All of them didn’t last long, though.

“The Taliban have benefited from Pakistan’s generous hospitality for a long time and they know it’s now their turn to return the favour. Therefore, the negotiations would not break down without achieving something tangible. The two sides might reach an interim deal in which they remove the irritants and agree to continue discussion on bigger issues,” says Gen Inam.

Dr Barak, however, is not optimistic about the possibility of a lasting deal. “Even if there is a deal, it will not survive for long because the TTP does not have a strong motivation to end the conflict with Pakistan,” he says. Jenkins is not optimistic either. “The political terrain is constantly shifting, requiring constant recalibration. Lasting peace may therefore always be a long shot.”

WHAT IF TTP DEFIES TALIBAN?

It is believed that the Taliban have promised to take military action if the TTP remains obstinate – and that it was this promise that has led Pakistan to revive negotiations. But Jenkins thinks it would be difficult for the Taliban to live up to the promise of military action against the TTP, which could be seen as a betrayal. There are already reports of tension between pragmatists and hardliners within the Taliban. Action against the TTP could deepen these internal divisions.

“The Taliban may risk their reputation and legitimacy if they take military action against the TTP. And as a result, Afghanistan may descend into security instability because the Taliban will be perceived as a puppet of external state actors, such as Pakistan,” adds Dr Barak. “The Khorasan chapter of Islamic State could also exploit the situation to demonise the Taliban and recruit TTP members.”

Jenkins agrees that the IS-K now seeks to attract dissatisfied Taliban veterans demanding that the jihad continue as well as those who simply have few peacetime prospects. The Taliban’s abandonment of the TTP could prompt an exodus. “Fear of losing followers to the IS-K also constrains what the TTP can agree to with Pakistan. In the same way it can attract disgruntled Taliban veterans, IS-K could also attract TTP fighters convinced of eventual success and unwilling to accept any compromise. TTP dissidents have pledged allegiance to IS-K in the past, others could do so in the future,” he says.

Gen Inam agrees that the fear of losing TTP cadres to IS-K could be one of the reasons for the Taliban reluctance to take on the TTP. However, he lists three possible main reasons for the IEA’s reluctance to take on the TTP. “1.) The two have combat affinity as they have fought alongside each other against the US-led foreign forces; 2.) Some in the IEA cadres see fighting the “TTP mujahideen” as un-Islamic; 3.) The IEA lacks the capability to take on the TTP, especially at a time when the Taliban are struggling to consolidate their rule in Afghanistan,” he says.

Dr Barak thinks the Taliban could also be trying to play a double game: selling a different perception to regional and international actors by peddling themselves as peace-brokers to international community while harbouring the terrorist groups. But Gen Inam doesn’t buy this perception. “I don’t think the IEA could use the TTP as a residual leverage. For them, relations with Pakistan are more important than the TTP,” he says.

AVAILABLE OPTIONS

Pakistan has achieved a convincing victory against the TTP in the erstwhile tribal regions by decimating their command and control system. This victory was achieved at a heavy cost – both in men and treasure. Acquiescing to TTP’s unreasonable demands, such as reversal of the FATA merger, a blanket amnesty for its fighters as well as allowing them to carry their weapons throughout the country, would be akin to unraveling the hard-earned gains. This would also undermine the trust in state power.

So, what options Pakistan will have, if talks fail? Dr Barak says Pakistan could a.) demand extradition of TTP’s members from Afghanistan; b.) cease efforts to stabilise Afghan economy and win global legitimacy for the Taliban rule; and, c.) take military action against the TTP.

Gen Inam says Pakistan could step up IBOs with on-ground military mobilisation. It could also extend more leverage and incentives to the IEA to wean its reliance on the TTP by amplifying formalised trade, border, immigration management with a view to public diplomacy, specifically via local outreach and context.

Pakistan may also go for cross-border surgical strikes, including covert decapitation attempts as well as the use of armed drones in an attempt to wean away malleable from hardline leaders. Pakistan could also attempt to divide the TTP through monetary and political inducements.