Gandharan art was once the thriving artistic tradition in Taxila, inspiring widespread replication of its intricate designs. These sculptures, carved from grey schist, a rock containing crystal fragments, showcase a civilisation from the past whose rich history helped shaped modern day Pakistan. Artisans in Pakistan who make their livelihoods form studying and creating historically accurate versions of Gandharan works have long celebrated this civilization through their creations.

But over the past few decades, making Gandharan style art has gotten more difficult as a result of Pakistan’s Antiquity Act of 1975, sections 25 and 30, which bans the reproductions of replicas of Gandhara sculptures. Critics say this law which intends to stop the replication of Ghandaran art ignores the repercussions for local industry, causing irreparable damage to a 2,000-year-old artistic tradition.

The fragrant lands

As far back as the middle of the 1st century BC, the Gandhara Civilisation thrived in what is now northern Pakistan and Afghanistan. Gandhara's name is thought to derive from the Sanskrit words Qand/Gand, which means "fragrance," and Har, which means "lands," As a result, Gandhara might be summed up as the "Land of Fragrance." Qand/Gand may have sprung from Kun (meaning "well" or "pool of water," as evidenced by place names like Gand-ao or Gand-ab (pool of water) and Gand-Dheri), which is a more plausible and geographically supported argument (water mound). The territory may have been known as the "Land of the Lake(s)" in addition to Yarkand and Tashkand (a stone-walled lake). When it rains heavily in the Peshawar valley, the marshes look more like lakes because of the excellent drainage system and water control management of the time.

Gandhara was thought to be a triangular region 100 kilometres east-west and 70 kilometers north-south. The Swat, Dir, Buner, and Bajaur hills, as well as the rest of Pakistan's northern border, were all thought of as part of Gandhara. It’s cultural and political dominion extended as far as the Kabul Valley in Afghanistan and the Potwar plateau in Pakistan's Punjab state, but the boundaries of Greater Gandhara didn't stop there. In fact, at one point in time, the Buddhist city of Mohenjo-daro was built on top of the ruins of a stupa and a Buddhist city in Sindh. Remains have been found and are still being found in the Gandharan cities of Takshasila, Purushapura, and Pushkalavati.

The lands that the Gandhara culture called home had in common a deep regard for Buddhism and a willingness to absorb the Indo-Greek artistic heritage that emerged in this region following Alexander's incursions into India during that time period. In historical records, Cyrus the Great (r. c. 550-530 BCE) is referenced, although Gandhara has not been documented in detail until the 7th century CE pilgrimage of the Buddhist monk, Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang) – Gandhara's greatest achievements had been attained and it was on the verge of collapse when he travelled there. Because of his careful adherence to ancient Buddhist sources, he provided the first account of the region's cities and places to have survived to the present day. This narrative was helpful in recognising modern-day artefacts from the region as belonging to the Gandharan region of India.

The art of the Gandhara

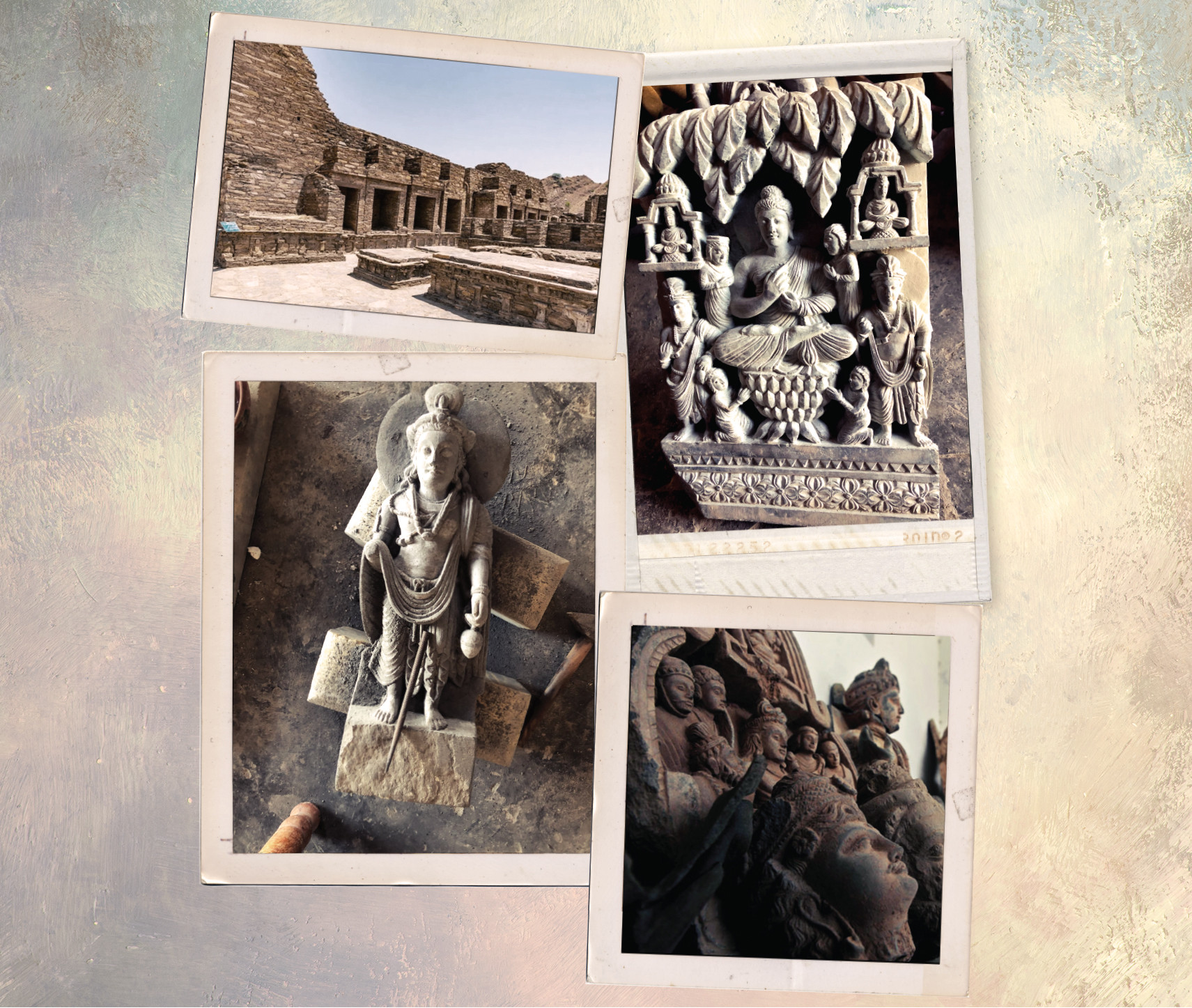

The artistic tradition known as Gandharan art dates back to the 1st century BCE and encompasses all aspects of painting, sculpture, ceramics, and coinage. When King Kanishka of the Kushan dynasty deified the Buddha and introduced the Buddha image for the first time, it truly took off. From small Buddhas to huge statues of the deity at places of worship, these images were spread across the region. Buddhism saw its second renaissance under Kanishka's reign, following Ashoka's.

So much of the art was focused on religious values that even everyday things had religious symbols on them. Both kanjur stone and schist stone were employed as the building materials.

There are many decorative aspects in Gandharan art that are built upon the use of Kanjur, which is a petrified rock that can be shaped easily into numerous shapes. Plaster is applied to the stonework once the basic shape has been carved out. Several things were embellished with gold leaf and diamonds. The schist stone statues' maximum transportable size was 2.5 square metres; larger clay and plaster statues and reliefs were used.

As depicted in this collection of sculptures, the Buddha was venerated in the same way every time, according to their consistent style. With his hair twisted into a bun known as the Ushnisha and an expression of contentment on his face, Buddha is always shown in basic monastic clothes. These sculptures were once painted in vibrant colours, but now only the plaster or stone remains; only a few artefacts have been unearthed with their original hues still intact.

In the region, several cults commissioned Buddha images, each with their own distinctive identifying characteristics, such as laksana (divine marks), mudra (hand movements), and diverse garments. The halo and Buddha's basic clothes are instantly recognisable in these paintings, which always feature him as the main character.

Many mythological figures, including couples, gods, demigods, celestials, princes, queens, male and female guards, singers, royal chaplains, soldiers, and also simple people, are seen in these scenes. The Bodhisattva, who represents the Buddha before he acquired enlightenment, is one of the most enduring representations of Gandharan art, second only to the Buddha himself. Gandharan art depicts numerous Bodhisattvas from Buddha's previous lifetimes, including Avalokiteshvara, Maitreya, Padmapani, and Manjsuri. Images of the Bodhisattva represent a higher degree of luxury than Buddha images, with a variety of attire, poses, and mudras that distinguish the numerous incarnations of the Bodhisattva from one another.

The keepers of history

Artisans of Gandhara sculpture have long sought to capture the essence of the civilization in their art, which they often sold to make a profit. They offered outsiders a window into Gandharan civilization, creating a vital connection to that historical narrative. Through the lens of these master craftsmen, the public history as a kaleidoscope, constantly surprising us with relevant insights into today’s world. But now these lessons have stopped coming in from Taxila, once the capital of Gandhara.

“We are the few last craftsmen of this fascinating art in this region,” said Iftikhar Ahmad, who has been a custodian of Gandhara art and sculpture for three generations. Like his father, he has been around the world on official academic invitations from universities to speak about this craft. But he said the government’s restrictions and other pressures are making it more and more difficult to keep the tradition alive.

He said if the government fails to amend the Antiquity Act of 1975, there may be no hope for the revival of the craft. This discipline was not considered when the law was created, Ahmad said, despite a shared concern for the study of civilizational memory and heritage.

The Antiquity Law is an antiquated relic of the past, said Dr. Nadeem Omar Tarar, an anthropologist and Gandhara Chair in Cultural Studies at The University of Wah. He said the law must be revised to consider the other side of the story. “Ironically, the word tourism does not enter the Antiquity Law of Punjab,” Dr. Tarar said. “The law has specific clauses that the concerned departments must amend, especially those that forbid the reproduction of heritage artifacts, killing the local artisanal industry.”

More than anything, this law lacks an understanding of the traditional artistic viewpoints that local artisans possess. Without that, it does not appreciate the role of these creators in upholding a sense of continuity with the past, since replicas and reproductions aid the public’s understanding of history. How viewers perceive these artworks is based on their opinion, but it can’t be denied that cultural and historical knowledge is essential in making high-quality replicas. Not everyone can produce an authentic replica, but professional artisans have this skill set.

Dr Shaila Bhatti, associate professor at the National College of Arts (NCA), said an antiquity law is vital because of the illegal trade of Gandharan artifacts that are either sold to private collectors or museums. But she said an important distinction needs to be made between replication for this purpose and replication done by local artisans on a small scale, who are empowered by being able to practice this craft.

Instead of banning artisans from producing these replicas, she encourages a law that empowers them to keep this tradition alive and allows them to transmit knowledge through generations. “They can live off this art will they keep it alive and pass it on,” Bhatti said. She said reproductions and replicas only aid the public’s understanding of the past because they allow tourists to see how this art is produced. She argues this ownership of craft is an integral part of a nation’s past and present.

An expert in the visual culture of South Asia, Bhatti said such work done by local artisans could be celebrated in Pakistan. She said the country needs to create laws to protect the skills and livelihoods of artisans, so their craft doesn’t suffer the same end as other indigenous arts in the country. She argues Pakistan should create a public platform that will enhance knowledge of Gandhara culture.

Dr Samina Iqbal, a renowned art historian, visual artist, and associate professor at Lahore School of Economics said clear distinctions need to be made between genuine replicas and fake replicas. She said genuine replicas are signed and identified as reproductions, which sets them apart from replicas that are made to look real for resale. Replicas that are marked as such are crucial to maintaining the rich history of Pakistan, while reproductions sold in the market as originals are problematic and criminal.

Revising laws saves history

There are not many well-known events recorded from Taxila, so to comprehend what it all means, one must look at the artifacts that remain from this period. Just as we have learned to carefully discern historical texts, we also have learned how to discern the honesty of artwork. Even if an object is a replica, we have structures of knowledge that let us ask probing questions about it, said Dr. Samina Iqbal, an art historian at the Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation. “Nothing makes sense without context, be it an object, text, visual, or being.”

She said history provides the context to ground people and objects in their context. Although the artifacts are not originals, the place they came from has a voice again thanks to the artisans that created them. This visual construction is the result of thousands of years of lived experiences, which she said can be discerned from modern replicas as well.

Signals from the past are getting weaker as traditional knowledge of Gandharan style and sculpture in art dies out. Without visual representations in Pakistani homes and institutions, some worry the next generation won’t have a clear understanding of their heritage, history, and identity. They lack concrete visual signs that remind them of their ancestry and the civilization that came before Pakistan’s statehood. As a result, young people grow up without cultural curiosity, only celebrating the more recent parts of their country’s identity.

When people travel to tourist destinations of historical importance, they look for souvenirs to take back home and remind them of the experience. Unfortunately, tourists who once held their Taxila mementos dear don’t have souvenirs to take home anymore. “This is a miserable and sorry state of our tourism policy,” said well-known local historian, Raja Noor Muhammad Nizami.

Taxila and other Gandhara sites were once beloved tourist destinations for people around the world where hundreds of families made a living by making Gandhara sculptures and art. “[The] government failed to support the art and tourism in the region dislodged the whole community,” Nizami said.

Residents like him are bitter about how the government has handled the preservation of local heritage and they blame officials for neglecting their cause in favour of less important ones. “They are wasting money,” Nizami said. “They are not sparing a rupee on the development of local heritage and the well-being of local communities.”