In a dusty refugee camp some 90 kilometers from the Chaman-Spin Boldak border crossing, a group of 50 Afghan refugee girls recently accomplished a little-recognized but mighty feat: they passed the annual intermediate exam.

For the past seven years, an initiative pushing for girls’ education in Saranan camp has seen success, with 185 girls completing their secondary education at Ghazi Amanullah Khan high school. Among the girls to pass the exam this year is Palwasha, 18, who lives in Saranan refugee camp in Balochistan. “My happiness knows no bounds for achieving one of the milestones in my life,” she said. “My dream of getting an education is realised today.”

Access to free education has long been a distant dream for Afghan refugees, with financial barriers for many refugee families contributing to low enrollment rates of Afghan children. Afghan girls are often deprived of the right to education because of financial problems and cultural barriers. Illiterate parents are often not aware of the importance of education for girls and believe their daughters should stay at home instead of attending school.

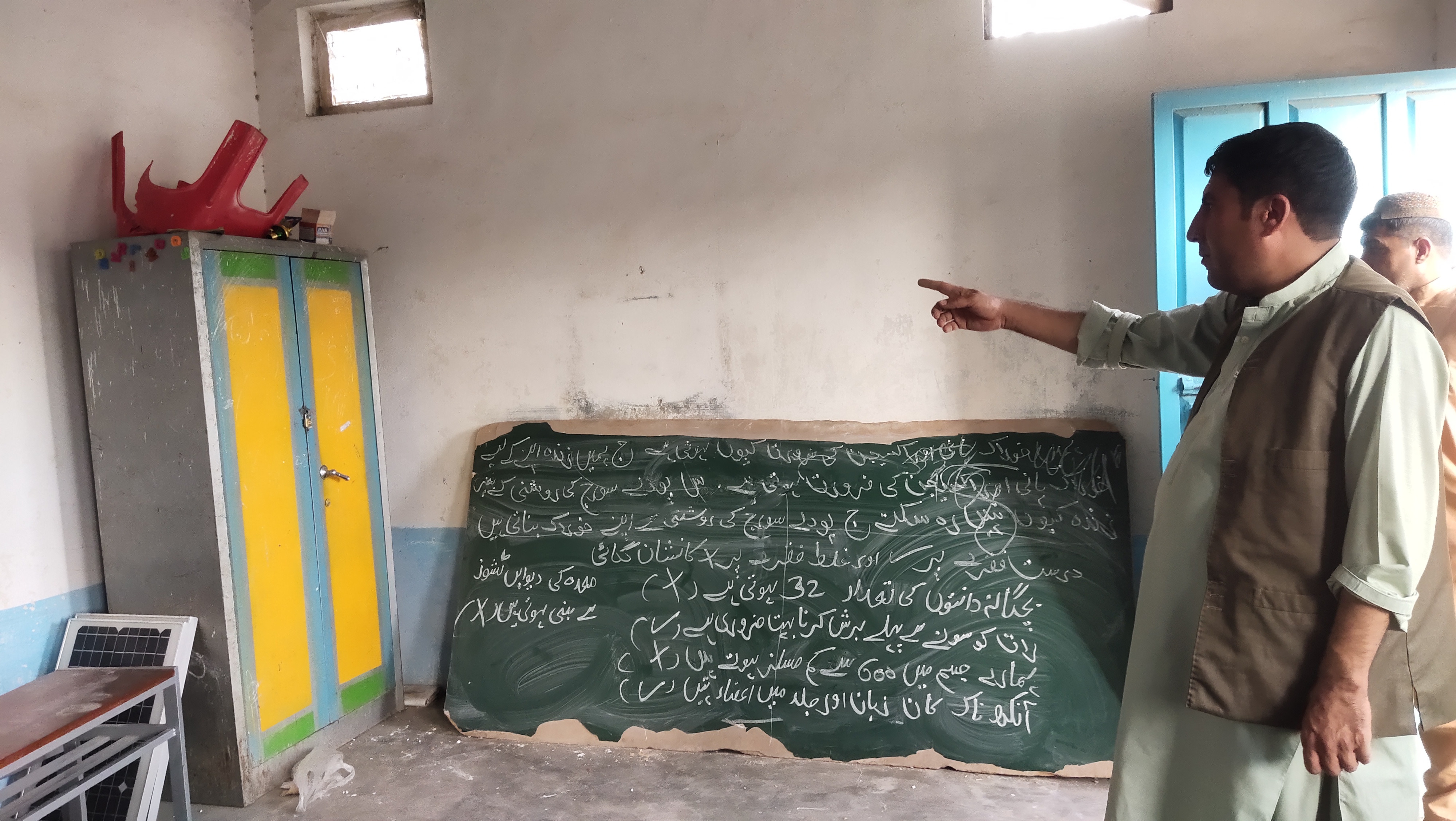

Schools in Saranan

In 1993, the Ministry of SAFRON established two schools at Saranan camp. Over time, Save the Children, an international humanitarian organization, opened more schools for boys and girls in the camp. When these schools opened, the community – composed mostly of labourers and daily wage workers – strongly opposed girls’ education, especially in co-educational settings.

The school hired teachers from the provincial capital, Quetta, to teach the girls because there were no female teachers in the slum. After a few years, the school stipulated that any girl who passed the sixth grade and any boy who passed matriculation would get a job as a teacher.

Zahir Khan, known as Zahir Pashtoon, a former student at the school from Sari Pul province in Afghanistan, pushed hard to establish a girls’ education project. Eager to study, Khan passed the written test and was hired as a teacher for boys and girls during his free time. Due to the negative attitudes of the community, the girls’ school was closed but later reopened because of Khan’s efforts.

Those efforts eventually bore fruit, and the primary school was upgraded to a secondary school called Ghazi Amanullah Khan Girls and Boys High School. Now, the school holds walks, rallies, and seminars to encourage more families to enroll their children in educational institutions.

In addition to his academic responsibilities, Khan is also involved in social activities for the welfare of the Afghan community, including people with disabilities, orphans, and widows, with the help of various national and international humanitarian organizations. He continues to strive for access to education for all Afghan girls in Balochistan,

Saranan camp is the only refugee camp in Pakistan where girls have access to education. A member of the community there estimates that around 7,000 Afghans, 4,000 of them girls, are now studying at Saranan camp schools run by the United Nations Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Refugees in Balochistan

Saranan is the largest refugee camp in Pishin Balochistan, with a population of 50,000. In the camp, Afghan children wear the national flag of Afghanistan around their necks while others fly the white flag of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan in their homes, mosques, and shops. Refugees at Saranan camp are from Afghan provinces of Jawzjan, Faryab, and Sri Pul, and most of them are Pashto-speaking.

When the Soviet forces invaded Afghanistan in 1979, millions of Afghans fled violence in their home country, settling in refugee camps around Pakistan established by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Of the 51 refugee camps in Pakistan that are still operational, 10 are in Balochistan, which shares a border with war-torn Afghanistan.

UNHCR data shows that Pakistan currently hosts 1.4 million registered Afghan refugees and another one million unregistered. Half of the Afghan refugees who came to Pakistan settled in ten refugee camps in different parts of Balochistan, including Pishin, Noshki, Muslim Bagh, and Loralai districts.

According to Khan, Afghan refugees in Balochistan reside in Nawai Saranan, Surkhab, Malgei, Zhar Karez, Posti, Leji Karez, Ghazgai Minara, and Katwei camps. In 2007, Gardi Jungle and Jungle Pir Ali Zai camps were closed by the government.

Girls’ education in Afghanistan

Previously, the curriculum taught in Afghan refugee villages was the same as the curriculum taught in Afghanistan. But in 2018, the UN refugee agency decided to switch to the Pakistani curriculum in refugee schools in line with the global education policy that encourages refugee communities to adopt the host country’s style of education.

Last year, the Pakistani government introduced the Single National Curriculum for primary level students in the country. Balqisa, a sixth-grade student at the Afghan refugee camp Katwei in Loralai said she isn’t happy about that decision because it isn’t in her mother tongue. Instead, courses would be taught mostly in Urdu. For populations that speak Dari and Pashto, this could be an added challenge in grasping the material taught in the curriculum of their host county.

Still, Afghan girls in Pakistan may fare better than girls in Afghanistan, since the Taliban government has recently banned girls’ education in the country. Last month, the Afghan Ministry of Education said that girls’ schools would remain closed until they could implement a strategy to educate them according to Islamic law and Afghan culture.

The Taliban has backtracked on promises that girls would be able to continue studying under their leadership. Most girls in the country have been out of school since the group took control of Afghanistan last August, and the Taliban's March deadline for letting girls return to school was not met. The U-turn in policy created an uproar among many in the international community, who condemned the Taliban for going back on its word. Female students in Afghanistan reacted to the decision with disappointment and sadness, even holding protests to demand their right to education.

The Taliban’s opposition to girls’ education has been a defining feature of the group’s leadership. When the group was in power in Afghanistan from 1996-to 2001, they banned female education and employment for women in most sectors. When the group came to power again in 2021, its leadership appeared to be divided over what conditions should be put in place for women to study. Until now, they haven't made a final decision on this matter.

Girls faced obstacles in getting an education in Afghanistan even before the Taliban took over. Although most girls in urban areas went to school, many in rural areas did not -- either because they didn’t have easy access to educational institutions, or because their families didn’t feel it was culturally acceptable to send them. There is still a prevailing attitude in some Afghan communities that women should remain at home for their safety or other cultural reasons.

Girls fight to learn

These attitudes are also prevalent among some Afghan refugee communities in Pakistan, where families that want to send their daughters to school can face pushback. Most success stories are the result of concerted efforts by a community member who recognizes the importance of female education. “For girls’ education, it is necessary to persuade the parents and change their mindset,” Khan said.

In many parts of Pakistan, schools for girls either don’t exist or they are located too far from refugee villages to be reachable, making co-educational schools the only option for some girls. This continues to be seen as a major deterrent for some families, hurting some girls’ chances of getting educated. The students who have succeeded to pass their exams in Saranan are some of the lucky few who have an all-girls facility available to them.

Nevertheless, access to education for Afghan refugees in Pakistan has been enshrined in law and policy and cultural barriers remain a bigger hurdle for many girls to access education than the availability of schools. Khan said there are currently 1,300 children – 600 girls and 700 boys --- in Saranan camp studying in a single school. There are six other schools in the camp composed of more than 7,000 Afghan students.

Many initiatives have sought to address the problem of low attendance of refugee students in schools in Pakistan but access for girls’ education still lags behind. To overcome the stigma attached to girls’ education, Pakistan needs to take concrete steps to address these problems through policy. Afghan refugees have requested help in this regard from the SAFRON ministry, the government of Pakistan, the UNHCR, and other donor agencies working on education.

Despite the challenges that come with fighting misconceptions about girls’ education, Khan said he remains committed to ensuring every Afghan child has access to education in Pakistan. “Pakistan particularly Balochistan is our second home,” he said. He congratulates the Afghan girl students on their achievements and urges them to become agents of change.