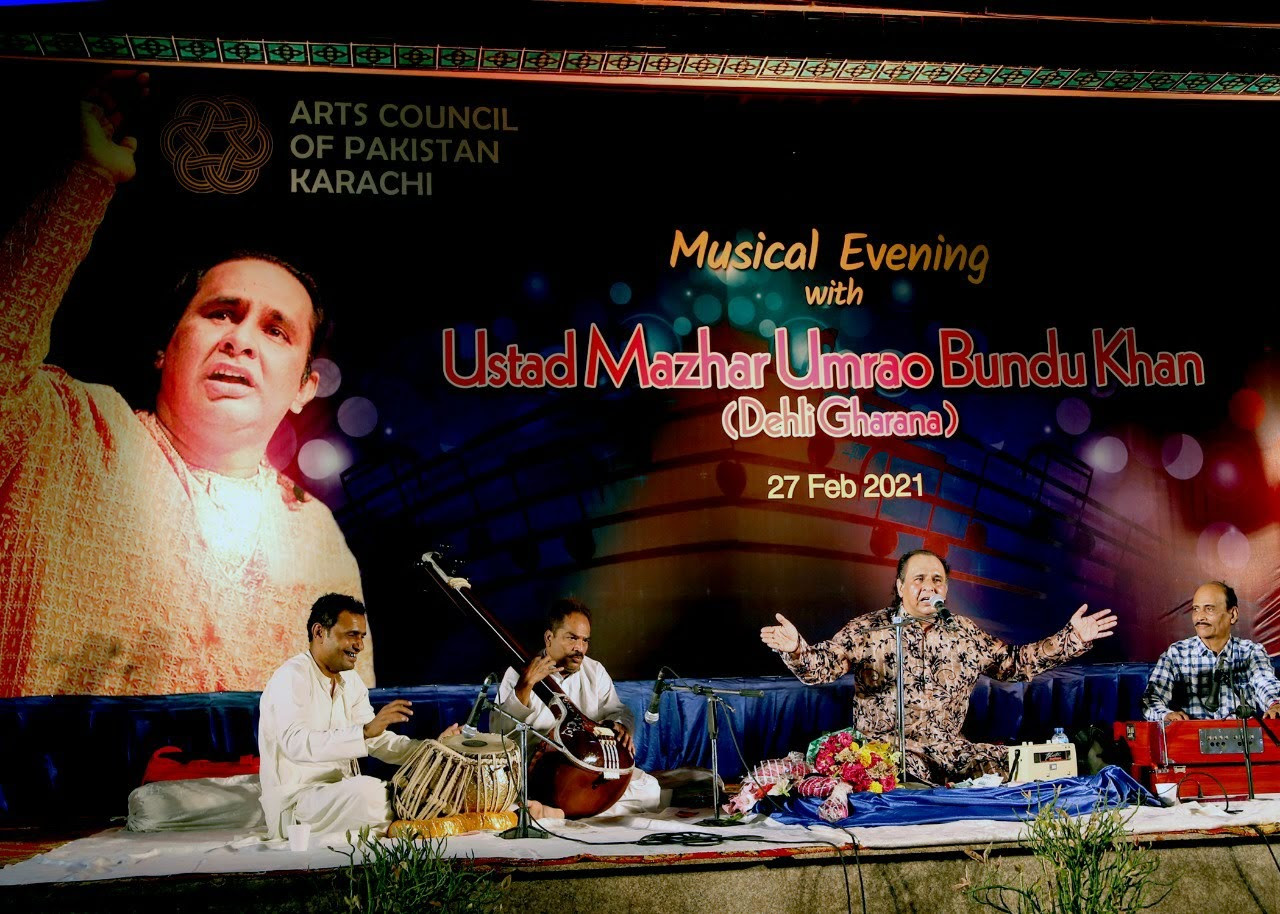

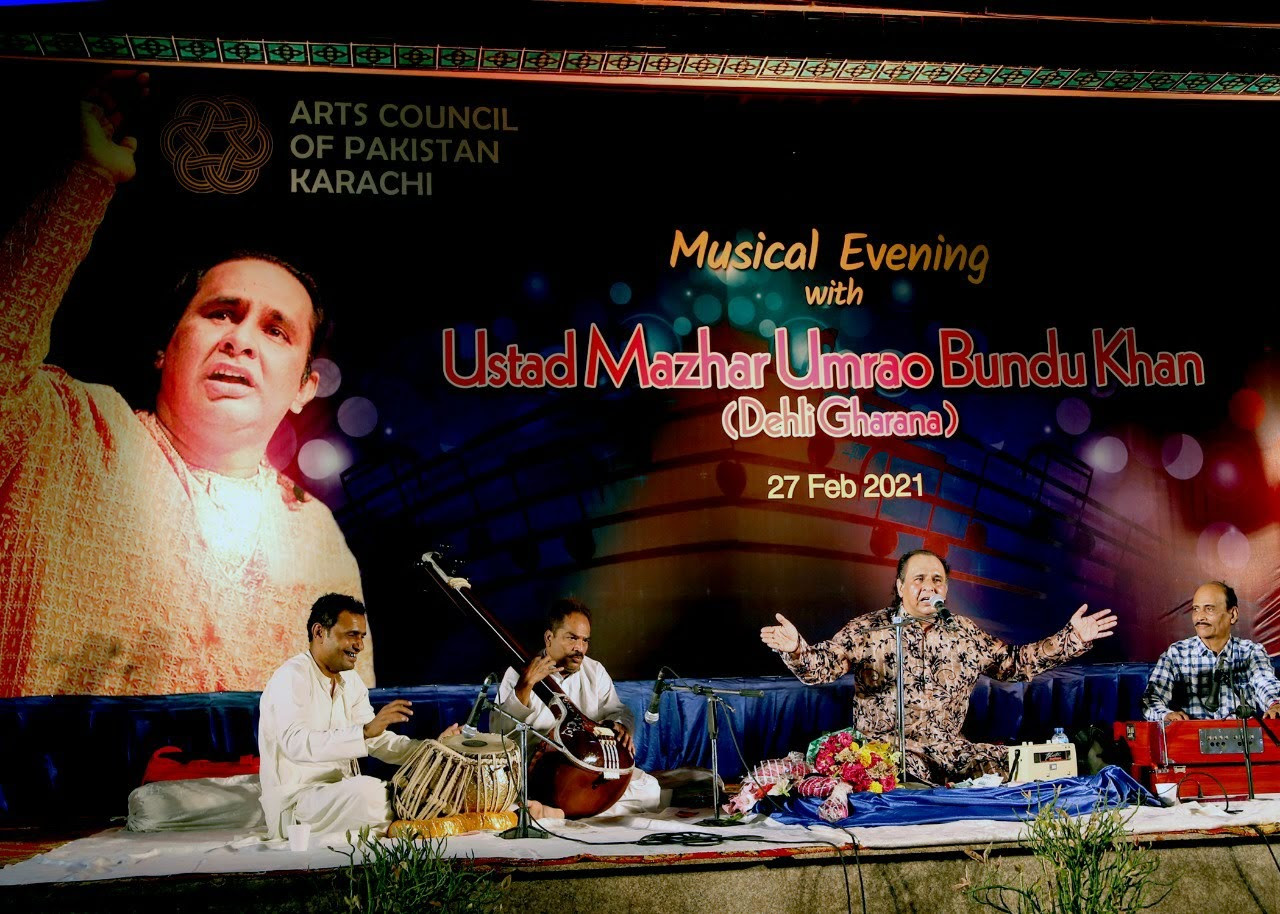

Ustad Mazhar Umrao Bundu Khan is the proud heir to the legacies of his grandfather great sarangi player Ustad Bundu Khan and father Ustad Umaro Bundu Khan of Delhi gharana.

With father and grandfather both having achieved the honor of Pride of Performance for remarkable accomplishment in the field of music, in the initial years of his career Mazhar worked with National Bank of Pakistan.

He narrates, “I have worked in a bank for 19 years. But on a fine day after reciting the Quran Sharif, a voice within me said that I should leave my job and devote myself completely to music. And since that day I have been dedicated to music.”

The Express Tribune’s interview with the classical ustad was more like a script of lyrics and musical notes. The maestro lets alaaps and bandishes free to flow in the environment as he blends notes and ragas to explain the scheme. His deep voice, elegant delivery style, and composure are enough to merge his audience with the words he sings. In an age when classical music is fading away, ustad Mazhar carefully and with ease uses his vocal intonations, voice, and mood to add life to the classic music. What makes him even more special is his humble and down-to-earth behaviour. Perfect intonation, respect for the structure, grammar of the raga, clarity in taans or swift melodic passages, and preventing the raga and the khyal composition from losing their original character and transforming into a thumri, are some of the characteristics that he mentions. He demonstrates his vocal and tonal range that he had developed as per the instruction he had received and the practice regimen that he had followed from his grand ustads of famous Delhi gharana.

STF: Why are people losing interest in pure classical music?

UMK: Classical music is serene. There are three grades in music is the composition, rendition of ghazal and singing. Classical music was well received till it was measured as fine arts. But it lost value after the 1980s after its inclusion to showbiz. This genre of work needs refined skill and careful understanding of its art. In contrary, ghazal is the rendition of memorised lyrics. People these days have no time to acquire the skill and prefer singing or listening to simple notes.

STF: Some singers say that they can literally see colors of notes. Do you also visualise them?

UMK: Of course notes are very powerful. One can visualise through dedication. There are two aspects of music--melody or tune and rhythm or bit. The melodic aspect in Indian classical music is called musical notes. There are 12 notes and it is really not a joke to learn them all. One can understand the depth only after 20 to 25 years of arduous riaz.

STF: Which is your favorite raga? How you do transition from one raga to another in a composition?

UMK: Each raga has its own sweetness. But I love bhairvi, piloo and purvi. These are euphonious. Transition is the variation of scales called chal or move that connects two ragas. Those who have practiced can detect the transition easily.

STF: Please explain the structural requirements in the ancient system of ragas.

UMK: The parent scale of the structural scheme is based on 12 thaats or notes. These are Bilawal, aiman, khamaj, bhairav, poorvi, marwa, kafi, asavari, bhairavi and tod. Earlier there were 72, then the number of scales was reduced to 52 and now we practice only 10 of those. Earlier composers used to experiment new ragas. Now we hardly have time to create new things.

STF: Are you in favor of introduction of new ragas in the traditional system?

UMK: We can make compositions in a raga, but cannot create any new. We lack the spirituality earlier composers had. We can do new compositions like ghazals and geets from a raga but cannot create new ragas. In Pakistan, music is based on only 20 to 25 ragas. We have drawn out a limitation. Most of the people cannot explain the number of notes in a raga. Then how can we create new?

STF: Why are people today more interested in fusion of style than pure classical music?

UMK: There is a misperception about the word. Fusion is all about use of instruments. Like guitar replaces sarangi and drums are used instead of traditional tabla to produce high pitch. But the traditional arrangements of notations remain intact.

STF: Say something about styles of thumri. It is generally believed that the thumri form cannot be presented well by all artistes, as it requires a different sensibility that is not easy to come by.

UMK: Thumri is a light form of classical music basically weaved within light meter scheme of words and beats. It falls within the textual genre of classical music, but in some degree higher than the ghazal mood. Thumri is characterised by its romantic or devotional lyrics, and by a greater flexibility with the ragas but obviously not simple as ghazal. Anyone who has the knowledge of ragas can sing it.

STF: Before partition there was just one classical Hindustani Sangeet; how has the once-common musical tradition of Pakistan and India changed and diverged over the course of time?

UMK: Music was practiced in Arabic much before and it will continue till the world exists. Classical music is a product of greater Hindustan. Hazrat Amir Khusrau was pioneer of some of the most melodic of ragas and a poet of high merit. He introduced classical music in this subcontinent. He invented ragas too. There is no such thing like Indian or Pakistani. It is just the territorial boundary and identity.

STF: There is a list of major gharanas of khyal like Agra, Delhi, Gwalior, Patiala, but WHY only Banaras is often referred to as the gharana of thumri?

UMK: Indeed these gharans used to present high or low khyals. But Banaras was famous for brothel dance or mujra. It was not possible for the performers to dance to the beat of Khyals. Therefore, a craftier genre of music thumri was adopted to achieve perfection in dance that became famous as Banaras ki thumri.

STF: A large number of notable vocalists – Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Ustad Bundu Khan, Ustad Abdul Kareem Khan and many others – were sarangi players as well. So why is it that sarangi has fallen out of favor as an accompanying instrument amongst vocalists?

UMK: Pakistan owns some of the great sarangi players of this world. But my grandfather Ustad Bundu Khan was considered as the greatest of all. He was affiliated with Radio Pakistan and Ustad Nathu khan was related to Pakistan Television. In the year 2009 NCA in Lahore organised a concert and invited 16 sarangi masters. Only 10 could perform as others could not make it. Now there are only five sarangi masters, two live in Lahore, two in Karachi, and one in Islamabad. Sarangi is on the verge of extinction. There should be a planned move to teach the art to youngsters in order to keep the tradition alive.

STF: Tell us about some special memory of your childhood. How did you feel when you first played on stage?

UMK: First time I played on stage was between 1970 and 1971 on the occasion of my grandfather ustad Bundu Khan’s anniversary at the age of 5 while my brother was three. We performed aiman and jodhpuri. My first professional performance was for the Radio Pakistan in 1977. Then I never looked back.

STF: If new things happen during a performance –that are nothing like you had done before, would you still go ahead attempting them even at the risk of failing?

UMK: Yes it happens but I never failed by the grace of Allah. I still remember once while performing in Delhi, I was requested to sing Ataullah Isakhelvi’s theva. Attaullah sahib has followed bhairavi but I performed there in malkos. It was liked and well-applauded.

STF: What is important to make the ragas beautiful and interesting?

UMK: It largely depends on practicing. The more you practice the more you excel. It is important to do riaz. It refines the tune and voice both. Only then music becomes beautiful and interesting.

STF: You belong to the Delhi gharana of classical vocalists. What are the qualities peculiar to the followers of this school of singing?

UMK: I belong to Delhi gharana. My ancestors have been serving music for the last 800 years. My father ustad Umrao Bundu Khan is the recipient of Pride of Performance while my grandfather too was awarded with Pride of Performance and Sitara-e-Imtiaz. I was awarded Pride of Pakistan by the United Nations. The unique thing about this school is that it has produced masters of almost all instruments and classical vocalists.

STF: You have spent the whole of your life singing. Has it been worthwhile in terms of financial benefit?

UMK: I was a banker for 19 years till 2002. My father was my first teacher. I was 13 when he passed away in 1979. I went to India and learnt music from 22 ustads from within my family. I have achieved many honors. I feel accomplished and have no regret in my life.