“It was a very unusual scene for a seven-year-old boy to see so many men shackled and armed with big hammers and long chisels, breaking the rocks on the high hills located near Old Sukkur,” remembers the 75-year-old Daulat Ram aka Daula.

“On seeing my astonishment and confusion my father told me that the men were prisoners brought from Central Prison Sukkur to break the rocks on high hills for the construction of a college,” he said.

“‘But, why these men are shackled,’ I asked my father and he responded with, ‘You ask too many questions,’ adding, ‘I told you earlier that these men are convicted prisoners and therefore they are in shackles so that don’t run away.’”

Though his father’s reply should have been convincing for the boy, still some questions were were on his mind, but he didn’t asked further.

It was back in the year 1953 and later I come to know that those prisoners were brought to break the rocks on the orders of the then Sindh Chief Minister (CM) Abdul Sattar Pirzada, who remained the CM from 1953 to 1954. Abdul Sattar Pirzada was the father of veteran politician and father of 1973 constitution Barrister Abdul Hafeez Pirzada, a blue-eyed boy of Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

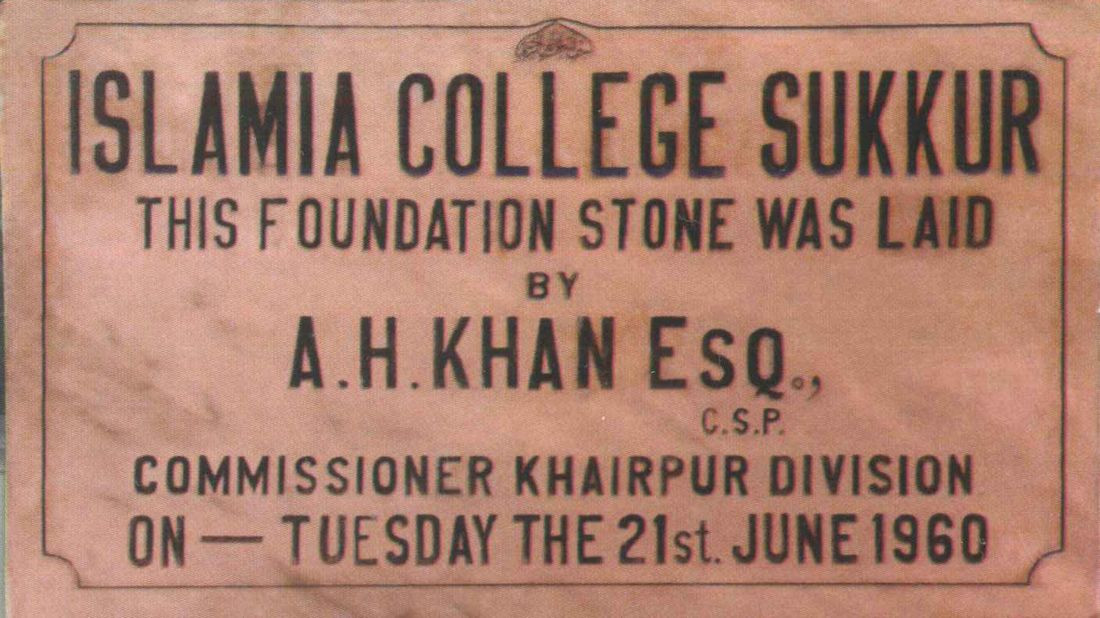

Islamia College was founded by one of the close aides of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Syed Hassan Mian, who remained the patron of the college till his death. Hassan Chowk Old Sukkur is named after Syed Hassan Mian.

Daula also remembers the construction of Shalimar Cinema on Minara Road in the early 1960s. So vivid is his memory of the old cinema that he also remembers the first movie to be screened in the newly constructed cinema was Mohammad Ali and Zeba’s ‘Charagh Jalta Raha.’ “As a teenager I was very fond of English movies, which were usually shown in the Regent Cinema,” he said adding, “at that time the ticket was 1 anna, but sometimes I didn’t have even that and thus I used to go the cinema and request the gate keeper - who usually relented - to let me in for free once the movie started.”

Life has never been kind neither for Daula’s parents and nor for Daula as he was born to extremely poor parents and is still struggling to make the ends meet. Daula’s father Fatoo Mal used to make shoes at a local shop, while his mother was an expert at hand embroidery of ladies and men’s sandals. Daula’s elder brother died at the age of three and thus Daula remained the only child of his parents. Daula’s father died when he was just 12 years old and luckily or unluckily he became the only male member in the family of two. “I have never been to school because my poor parents weren’t able to send me to school,” he says adding, “but I am a multi-talented man. I am an electrician, water pump mechanic and a shoe maker.”

At the age of ten, Daula joined one Deeno Baloch, who used to take goats from various houses in the morning and took them for grazing on the backside of Sukkur Barrage in Bachal Shah Miani, - which used to be a jungle at the time - and return in the evening. “It really was a fun for me to take care of hundreds of goats and take them for grazing,” he went on to say. “Deeno used to charge Rs1 per goat per month and used to give me Rs0.25 per month.”

Talking about a little dishonesty he did during his goat grazing days, he reveals while laughing that whenever he felt hungry, he used to drink milk direct from the teats of the goat and then punch the goat on its udder, which made it swell like it is full of milk and no one knew would find out that the goat was already milked. According to him, he continued this work till his marriage in 1973, which was when he began shoe making at a shop in Mochi Bazar Sukkur. He said that the owner of the shoe shop used to give him Rs5 a day, which was not enough to cater to the needs of my family and therefore apart from shoe making, he started to learn electric work and water pump repair work.

Being a hard-working man, Daula kept on struggling to earn enough to become well off, but it seemed that fate wanted him to struggle throughout his life and earn little. Daula’s first son was born fifteen years after his marriage and died at the age of two. Later he fathered two daughters and a son. Daula says, interestingly unlike his first son, which was born after fifteen years of marriage, each of his two daughters and a son were born within the gap of five years.

Daula married off his elder daughter, but her husband died after two years of marriage and she came back to live with her parents. Daula’s only son Roop Chand works at a cloth shop in Sukkur and earns Rs 10,000 per month, but it is not enough to pay rent of the house, apart from paying utility bills and other domestic expenses.

Sensing Daula’s hardship, one of his cousins began helping him pay his house rent and utility bills, thus relieving him from some of his financial burden. Still Daula and his elderly wife keep toiling hard to make ends meet. One of his neighbors provides ingredients to his wife, who makes poppadums and for that she is paid Rs100 per 100 poppadums. “Sometimes she makes 200 or more poppadums a day, but if she is unwell then her widowed daughter make poppadums for her mother,” he said adding, “now that I cannot do electric work anymore, due to my weak eye sight, I go around the markets and collect empty cardboard cartons.”

Daula lives in Rohri town and visits Sukkur on a daily basis on foot except for Fridays to collect empty cardboard cartons. Sometimes he says, “I go round different markets thrice a day to collect as many empty cardboard cartons as I can. This is not all,” he says, “while going through different market places I also collect empty pet bottles and pieces of iron or tin, which I use to store in the upper portion of a temple in Mochi Bazar. I only sell my ‘treasure’ when I need money badly, otherwise I keep on stashing the material and sell only when the room is of full of empty cardboard cartons and empty bottles,” he says with a smile. Replying to a question about how much he earns after selling the material, he replies, “roughly I earn around Rs.10,000 a month.”

Besides this, Daula also works part-time in a residential plaza in Mochi Bazar and gets Rs 5,000 per month. Sharing a story about finding Rs100,000 from an empty cardboard two months ago, Daula says that one day he went to Clock Tower as usual to collect empty cardboards, thrown on the road by shopkeepers. “I gathered all the empty cardboard cartons and brought them to my place and when I was opening the cardboard cartons, I found a packet of Rs1,000 notes,” he said adding, “I immediately closed the road facing windows and started counting the money, which was Rs100,000. Without uttering a word to any one, I left for home and gave the money to my wife, who received it with her mouth gaping,” he said. “She kept asking me who gave me this money and I replied ‘Allah gave me the money.’”

Talking about Hindu-Muslim harmony, Daula was of the view that Sukkur is comparatively a peaceful city, housing people belonging to different religions with harmony. “Sometimes, tension sparks between Muslims and minorities, due to wrong doing of some persons and emotionally charged people do some harm to the places of worship of Hindus or Christians, but the situation usually calms down when the elders from either religions sit together and sort out the differences,” he says. Recalling the desecration of the Babri Mosque in India back in December 1992, Daula says the reaction of Muslims was natural, due to which people attacked temples in the city, causing damage to the property, but that too was handled wisely by the elders of both the religions.