20 years of 9/11: ‘Khuda Kay Liye’ and the twin towers of Muslim anxiety

The issues caused by the binary of the good and bad Muslim continue to haunt Pakistan two decades later

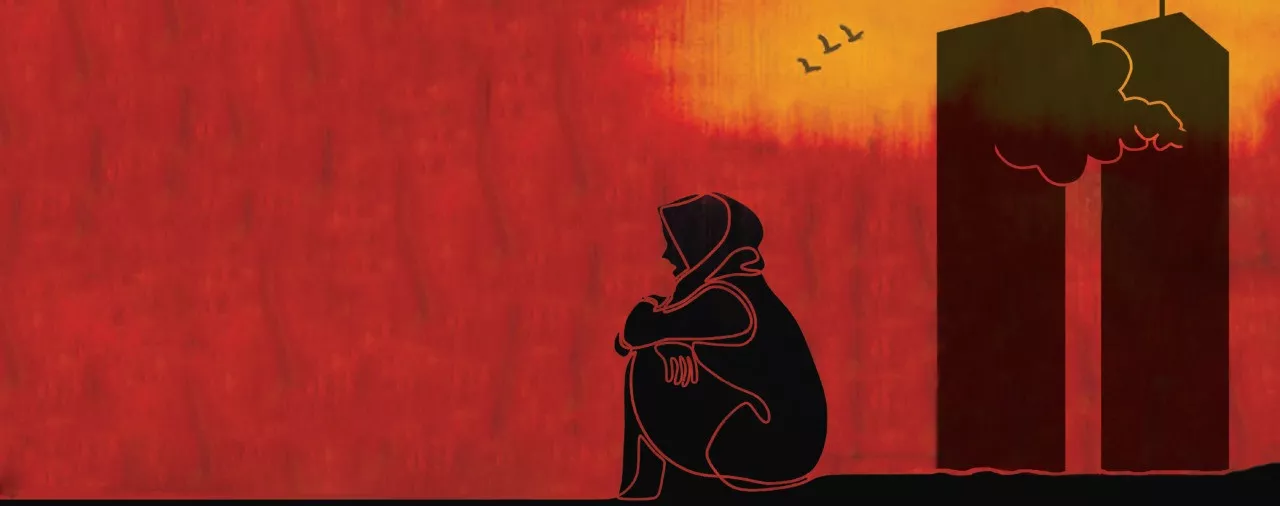

KARACHI:The 9/11 attacks caused a seismic shift in the way the world functioned, triggering a crisis of identity for Muslims across the globe. It is one that continues to shape the ebb and flow of politics and power in the Muslim world and beyond to this day. In the aftermath, the Muslim faith faced exceedingly negative scrutiny as beliefs that were thought to be held by those piloting the ill-fated flights became largely accepted in mainstream world media as the only interpretation of Islam.

Amid the fallout, in Pakistan, certain schools of thought were seemingly pitted against music and general freedoms. When it comes to questions of identity, ours is a country caught in a perpetual predicament. Due to its relative newness and its grounding in the idea of a separate homeland for Muslims, it has faced an uphill battle in trying to establish who a Pakistani is and to carve out space for itself in the international community.

Since its inception, Pakistan has grappled with what kind of Muslim can lay claim to the country – a process often complicated by ethno-sectarian divides. The 9/11 attacks and the subsequent War on Terror forced the state to not only specify what kind of Muslim it aligns with, but also with whom it does not.

This binary of the good and bad Muslim lies at the heart of Shoaib Mansoor’s 2007 film Khuda Kay Liye. Championed as the film that heralded the revival of Pakistani Urdu cinema, Khuda Kay Liye depicts the divide between the hardline Islam of the Taliban, and the softer, Sufi-centric Islam of music and mystics, presenting in its climactic scene, quite literally, a case for the latter. The film was hailed as a triumph, both at the box office and as a political statement against extremism. The then state-endorsed narrative of Sufism was what was needed to salvage a fractured nation and rescue it from the joyless clutches of hardliners. But twenty years on, the fault lines in Mansoor’s utopian vision have become glaringly obvious.

Following the contrasting trajectories taken by the lives of two musician brothers, Mansoor and Sarmad, with the former subscribing to ‘liberal’ values, and the latter becoming Talibanised throughout the film, Khuda Kay Liye offers a neat categorisation of the good and bad Muslim. Sarmad (Fawad Khan), under the influence of Maulana Tahiri (Rasheed Naz), begins to question the permissibility of music and marries and impregnates his British cousin Marium (Iman Ali), anglicised as Mary, against her will. His brother Mansoor (Shaan Shahid), meanwhile, goes to the United States to pursue music and eventually marries a white woman (Austin Marie Sayre) before being forcibly taken away by the FBI under false accusations of terrorism following 9/11.

1632741680-1/mobile_file_2021-09-27_11-16-25-(2)1632741680-1.jpg)

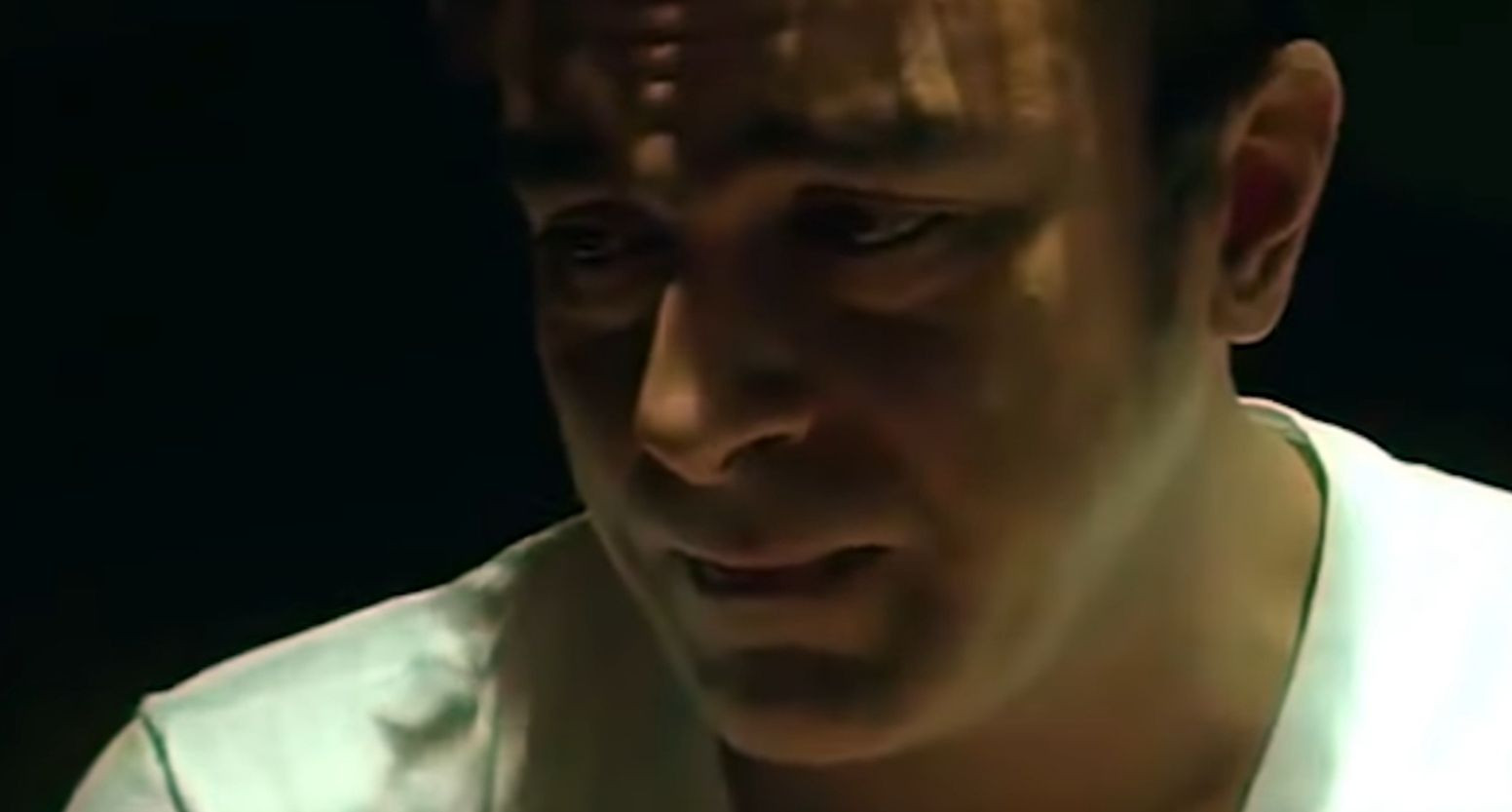

Sarmad, played by Fawad Khan, becomes Talibanised over the course of the film

In addition to the anxieties related to questions of what it means to be a Muslim in a post-9/11 world, music and its place in Islam are central to the film, and in many ways to the life of director Shoaib Mansoor. The filmmaker was instrumental in the success of Pakistan’s biggest pop band, Vital Signs. Co-writing the lyrics for their smash hits, from Dil Dil Pakistan to Do Pal Ka Jeevan, Mansoor worked alongside fellow band members and music industry giants including Junaid Jamshed, Shahi Hasan and Rohail Hyatt. However, with Jamshed’s turn away from music and towards a life of televangelism as a Deobandi cleric, the band fell apart. The breakup of the group is symbolic, however, of a much deeper cultural rift.

The real-life tension between Jamshed and Mansoor forms the basis of the fictional clash between Sarmad and his brother, whom the director named after himself, leaving no room for differing opinions on the question of inspiration. In fact, the filmmaker spoke openly about his distaste for Jamshed’s new way of life, where the latter deemed music, and most other forms of expressive art, haram. Khuda Kay Liye, according to Mansoor, was a way to bring those seemingly lost to extremist narratives of religion back into the fold of moderation, tolerance, and of course, pop music.

The film, then, presents itself as just that. A document of counter-arguments to be utilised against justifications of the banning of art and music to soothe the anxieties of young Muslim music-lovers caught in a crisis of faith. In doing so, the film attempts to exonerate ‘moderate’ Muslims of extremist crimes in the eyes of the rest of the world as well.

The scene in which Sarmad is taken to court serves as a face-off between Deobandi and Barelvi views on Islam. Maulana Tahiri, complete with heavily-accented Urdu and extremist views on women, weapons and western attire, defends his stance against music in court, deeming it haram and warning the jury of the consequences such an “irreligious” society will face when Islamic law is ultimately imposed nationwide. However, in perhaps one of the most heavily quoted scenes from the film, Maulana Wali, played by Bollywood’s Urdu-speaking sweetheart Naseeruddin Shah, a cleric with a home full of paintings and a perpetually spinning record player, cites religious texts to invalidate Tahiri’s claims against music and in favour of forced marriage.

1632741682-2/mobile_file_2021-09-27_11-16-25-(1)1632741682-2.jpg)

Maulana Wali (Naseeruddin Shah) and Maulana Tahiri (Rasheed Niaz) face off in court in the climactic scene of the film

Speaking of the miracle given to the Abrahamic figure of Prophet Dawood, Wali explains, “What miracle did God give to Dawood? Music. An incredibly melodious voice and such mastery over raags and rhythms that mountains would sway along when he sang.” He asserts later on, “Is it possible that God would employ something haram to be used in his praise?”

The evidence presented is crystal clear, and while the film is indeed grounded in a biased approach towards Tahiri, keeping the arsenal of quotable religious texts well out of his reach, often lending him an almost comically villainous quality, Wali wins the audience over with no questions asked or counter-arguments presented.

Khuda Kay Liye was embraced almost instantly upon its release by Muslims subscribing to Barelvi factions, or those who simply aligned with syncretic Sufi values of pluralism and tolerance. Most importantly, the film was given the go-ahead by none other than the man-in-charge himself, General Pervez Musharraf. Before Khuda Kay Liye was shared with censor boards, it was screened for Musharraf, consequently getting his seal of approval, which made getting through the censors a breeze. While the narrative is indeed bold, given the pervasiveness of Deobandi beliefs in the country and the constant threat of violence from the Taliban and other radical groups, the fact that it was supported by the state dims its revolutionary potential, at least in retrospect.

In the 1980s, General Ziaul Haq, with support from the USA and Saudi Arabia, trained and supplied fighters to the Afghan Mujahideen to fight the Soviets. A majority of these fighters belonged to the Deobandi sect, a puritanical branch of the Sunni Hanafi school that rose to prominence during British Colonial rule. Following the withdrawal of the Soviets from Afghanistan and the subsequent abandonment of the Mujahideen by the USA, Pakistan continued to maintain contact with the group now in power in the war-torn region of Afghanistan.

However, following the events of 9/11, a need for the Pakistani government to distance itself from extremist religious factions revealed itself, with Musharraf championing Barelvi views and Sufism in the national rhetoric as an antidote to extremism. However, it is instrumental to note that while Musharraf’s regime aligned itself with Sufism out of political necessity, the government pandered to conservative factions when needed.

With the post-9/11 government in Pakistan attempting to salvage its international reputation by forming a National Council of the Promotion of Sufism in 2006, as well as its support of the US War on Terror, when it came to furthering the rhetoric of “enlightened moderation” and tolerance, Khuda Kay Liye fit the bill perfectly.

The soundtrack of the film, composed by Rohail Hyatt, who later went on to gain massive success with the superhit show Coke Studio, contains tracks by the relatively obscure (at the time) Sufi singer Saieen Zahoor, with lyrics to songs like Bandya Ho penned by none other than Baba Bulleh Shah himself. While qawwali and Sufi kalam were a mainstay of Indo-Pak culture at home and beyond owing to the likes of the Sabri Brothers, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Abida Parveen well before 9/11, the subsequent rise of Coke Studio put pop Sufism on the global map as the ‘true’ interpretation of Islam, relatively secularised and well-protected from extremist tendencies.

With the extremists from the Deobandi school of thought driven to the fringes of society, the Sufi-centric Barelvi order gained momentum in the government. The Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) government furthered the ‘Sufi’ cause, empowering custodians of various shrines and parties such as the Sunni Tehreek, continuing the politicisation of Sufi Islam for strategic gains.

In its depiction of Maulana Tahiri vs Maulana Wali, extremism vs liberalism, Khuda Kay Liye fully discounts the anti-west sentiment that may possibly be harboured by those aligning with more ‘Sufi’-centric views. Wali presents a defense of western dressing, going as far as to condone inter-faith marriages, and Mansoor is brutally tortured to the point of immobility by American authorities but reiterates that he “doesn’t hate America” in a letter to his wife written before his irreversible injuries. The film’s obvious inclination towards Western appeal is apparent, and possibly a reason for its acceptance by the government at the time, but its message of tolerance in the face of opposing world-views does not fully translate into the real world.

Mansoor, played by Shaan, is falsely accused of terrorism and is tortured by American authorities

The vacuum left was to be filled somehow, and the Barelvis were more than up to the task. The last decade has seen a steep rise in cases of Barelvi extremism, often underpinned by anti-west issues most often relating to blasphemy. From the burning of cinemas over the release of an anti-Islam film in the west, to the barbaric lynching of student Mashal Khan over alleged blasphemy, Barelvi extremism is on par with that of extremist Deobandi groups like the Islamic State that bombed the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar during the dhamaal on a Thursday night, deeming the dance and the reverence of the saint as shirk.

Twenty years on, Pakistan faces the same threat, but from a different source, a direct result of the appropriation of religion to suit political interests. Perhaps, had Khuda Kay Liye delayed its release to some two decades later, the film would find it difficult to reach the screen altogether, given the treatment of films such as Sarmad Khoosat’s Zindagi Tamasha.

In March 2016, Junaid Jamshed was violently attacked at the Islamabad airport by a mob that chanted slogans against the singer-turned-evangelist, accusing him of blasphemy. In December 2014, Jamshed was booked for alleged blasphemy over one of his televised sermons that was thought to contain blasphemous remarks about a wife of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). A viral video of the assault was shared on social media following the incident. Regardless of the preacher’s previous plea for forgiveness, the mob can be seen attacking Jamshed with a militant resolve as the binary between the good and bad Muslim implodes in on itself. There are no Taliban in sight.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ