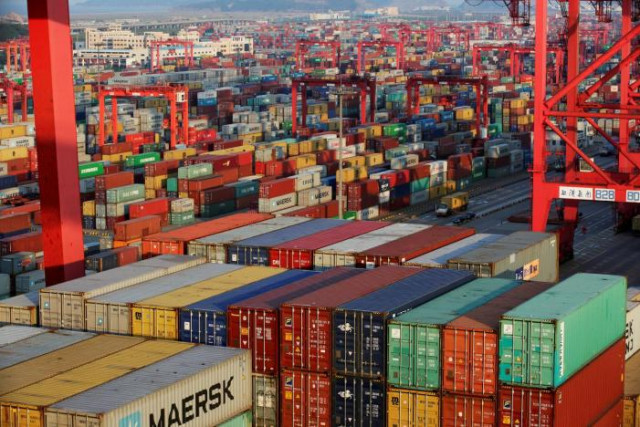

Growth-trade deficit trade off

Expansionary policies may aid growth but may also raise prices, current account deficit

Economics has been called the science of rational choice mainly for two reasons. One, as resources are limited, economies as well as firms and individuals have to decide to which use they may optimally put their scarce resources. Second, the policies that the government adopts have both intended and unintended — but not necessarily unforeseen — effects. So the government must be prepared to accept the rough with the smooth.

For instance, expansionary fiscal or monetary policies may accelerate economic growth but may also raise prices and current account deficit. Likewise, contractionary policies may bring down current account deficit and inflation but may also put the brakes on economic growth. Hence, macroeconomic targets may be achieved only at the cost some related economic indicators. As a result, the economic managers are often placed in a policy dilemma.

The Pakistan government is currently facing a similar, and all too familiar, dilemma. Because of its business-friendly policies as well as some favourable international developments, during FY21, the economic growth increased to 3.94% from 0.4% contraction recorded during FY20. For the current financial year, the government is eyeing close to 6% GDP growth.

On account of a record uptick in exports and remittances, which reached $25.64 billion and $29.37 billion, respectively, FY21 closed with one of the lowest current account deficits in terms of GDP (0.6%) in recent years. Yet the trade deficit increased to $31.05 billion from $23.16 billion a year earlier, as imports went up from $44.55 billion to $56.40 billion.

The increase in exports, imports, and trade deficit continues into the current financial year (FY22). In the first two months (July-Aug FY22), exports registered a healthy growth of 27.59% year-on-year to reach $4.57 billion. However, imports grew by a whopping 72.59% year-on-year to reach $12.06 billion. As a result, trade deficit, more than doubled (119.94% year-on-year increase to be precise) to sit at $7.49 billion.

These initial figures suggest that FY22 may close with a high trade deficit, even higher than the highest-ever $37.58 billion deficit recorded in FY18. Is the economy under the present government heading back to where it started three years ago: a healthy growth rate of close to 6% but undergirded by high trade and current account deficits?

It will be premature to answer the question in the affirmative. However, the figures on hand do confirm the familiar policy trade-off, which successive governments in Pakistan have faced. This trade-off can be put down to two economic fundamentals: one, from the supply side, the total product that an economy produces is either consumed domestically or exported. Exports represent the difference between the total national product and domestic demand. Exports and domestic demand are thus a drag on each other.

Two, from the demand-side, the total demand in an economy can be satisfied either by domestically produced products or foreign products. Hence, when the domestic demand increases on the back of export expansion, or for some other reason, the domestic and foreign products compete for capturing the increase in the national pie. Generally, and in the absence of a strong government intervention, the demand for both domestic and foreign products goes up. That is the reason economic expansion usually drives up the import bill.

The actual impact of growth expansion on import demand depends on several factors, of which three may be mentioned here. First, because of supply-side constraints the greater an economy’s dependence on foreign capital goods and raw materials needed by domestic producers, especially those which are export-oriented, the stronger will be the impact. The impact will also be strong if most of the fuel that is necessary for keeping the wheels of the economy moving has to be bought overseas. The more vibrant an economy, the higher is energy demand.

The third factor is conspicuous consumption. If the affluent section of society has the flare for parading their wealth, they will adopt a pricey lifestyle, which will induce them to buy more luxury consumer goods from abroad, thus inflating the import bill. The middle class will emulate the upper class lifestyle by buying cheaper versions of the imported products.

As Pakistan’s economy and society satisfy all the three above-mentioned conditions, growth expansion, as a rule, has had a strong impact on import demand in Pakistan.

Thus, when the economy and exports expand in Pakistan, imports also increase. The country’s persistently adverse terms of trade (ToT) indicate that on average import prices tend to be higher than export prices, as on balance we import more value-added products (computers and machinery) than we export (rice and textiles).

Thus, even if in quantitative terms, export increase matches import increase, in value terms import growth will considerably outpace export growth, thus exacerbating the trade imbalance. It follows that increased trade deficit is an inevitable outcome of economic and export expansion.

The top economic managers can opt for high growth and high trade deficit (expansionary approach); or they can go for low growth and low trade deficit (contractionary approach). But being successful in having both high growth and low imports and trade deficit — despite theoretically being the most attractive outcome — is highly improbable.

Thus, the present government when it came to power in August 2018 set out to reduce trade deficit by introducing import compression policies, such as letting the exchange rate depreciate, maintaining a relatively high benchmark interest rate, and imposing regulatory duties on imports. As a result, imports came down from $60.79 in FY18 to $54.79 in FY19 and further to $44.55 billion in FY20.

However, the import compression policies had the unintended adverse effects on growth and exports. Economic growth receded from 5.5% in FY18 to 2.1% in FY19 before the economy was hit by 0.47% contraction in FY20. Exports fell from $23.21 billion in FY18 to $22.97 billion in FY19 and further to $21.39 billion in FY20, registering year-on-year decrease of 1.0% in FY19, and 6.8% in FY20. In FY21, however, increasing growth rather than reducing imports became the priority, with fairly predictable results.

If the government persists with expansionary approach, it’s likely to get closer to achieving economic growth and export targets for the current financial year. But in that event it should be prepared to see imports and trade deficit rack up. Should it shift gears and put the high premium on slashing imports by pursing contractionary policies, it must be ready to see recession in both export and economic growth. Either way, the trade-off is inescapable.

THE WRITER IS AN ISLAMABAD-BASED COLUMNIST

Published in The Express Tribune, September 13th, 2021.

Like Business on Facebook, follow @TribuneBiz on Twitter to stay informed and join in the conversation.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ