In 2001, the US troops toppled the Taliban regime in less than three months, but it took them 20 years to give up their pursuit of an elusive military victory in Afghanistan. They marched in to “attack the military capability of the Taliban regime”, which had given haven to al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, but they are marching out virtually handing the country right back to the same militia.

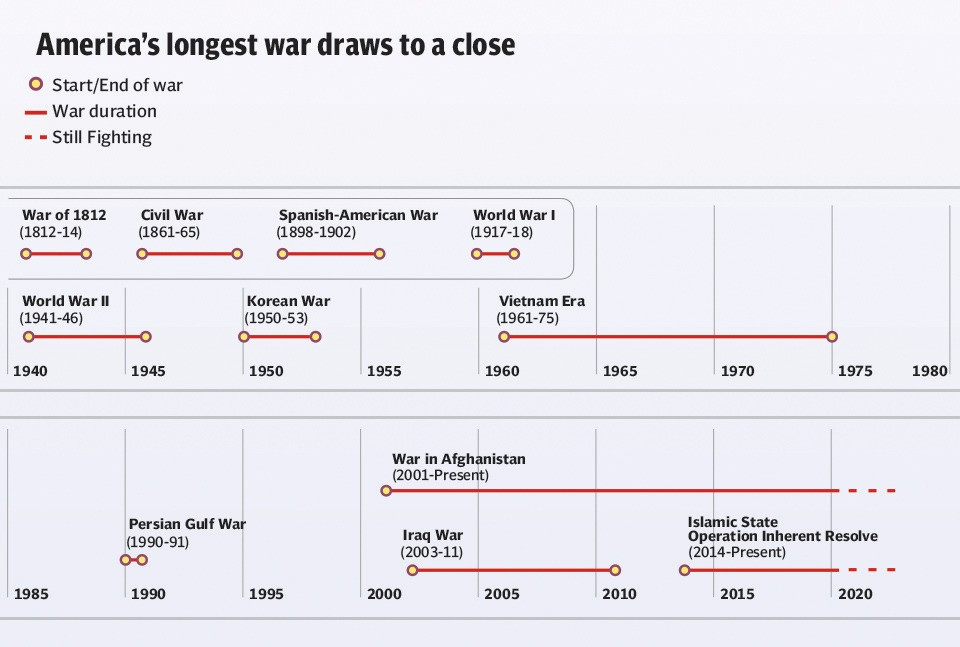

The US and its allies pumped in billions of dollars to build a nascent Western-style democracy only to leave it to fend for itself against the “regressive” Taliban. The human and material cost of the mission has been astronomical: countless lives lost and more than $2 trillion in taxpayer money spent. This begs the convoluted question: “What was the objective of America’s longest war?” Apparently, the objective, and the strategy to achieve it, kept changing with each president. And there lay the rub.

President Joe Biden wants to extricate himself from the war that bedeviled his three predecessors. Perhaps he is convinced that no amount of US boots on the ground could win him a convincing military victory. “War in Afghanistan was never meant to be a multigenerational undertaking,” Biden said last month while speaking from the White House Treaty Room, the same location from where President George Bush had announced the launch of the “just war” in October 2001. “We were attacked. We went to war with clear goals. We achieved those objectives,” Biden said as he announced withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan, beginning May 1, 2021. “Bin Laden is dead and al Qaeda is degraded in Afghanistan and it’s time to end the forever war.” If eliminating Bin Laden or degrading al Qaeda was the objective, then the US troops would have been out of Afghanistan long ago.

Design: Ibrahim Yahya

President Bush had clear objectives when he authorised Afghanistan’s invasion: to destroy al Qaeda, decimate the Taliban regime and prevent a repeat of the 9/11 attacks. Simply put, Bush’s approach was to overthrow the Taliban, pass on the baton to local allies, and get out. By December, this core objective was achieved, perhaps sooner than anyone could have expected. Secretary of State Donald Rumsfeld wanted to steer clear of the drudgery of “nation-building”, which he believed would only create a culture of dependence. Curiously, Bush decided to pursue what Rumsfeld was averse to. “By helping to build an Afghanistan that is free from this evil [of terrorism] and is a better place in which to live, we are working in the best traditions of George Marshall,” Bush said on April 17, 2002 in a speech at the Virginia Military Institute, evoking the post-World War II Marshall Plan that revived Western Europe.

Bush turned into a haphazard nation-building affair the Afghan mission he baptised “Operation Enduring Freedom”. In hindsight, the moniker has proven to be perversely apt given the war has endured for two decades. This is how the US changed tack and veered off in directions that had little to do with al Qaeda. This was a fatal mistake, a mistake that would set off a bloody insurgency and cost the US its initial swift victory against the Taliban. Over the next 20 years, successive US administrations would draw up and try fatally flawed strategies against an undefined enemy in pursuit of elusive objectives. And all these years, senior US officials would lie to the Americans – and to the world – making “rosy pronouncements they knew to be false and hid unmistakable evidence the war had become unwinnable.”

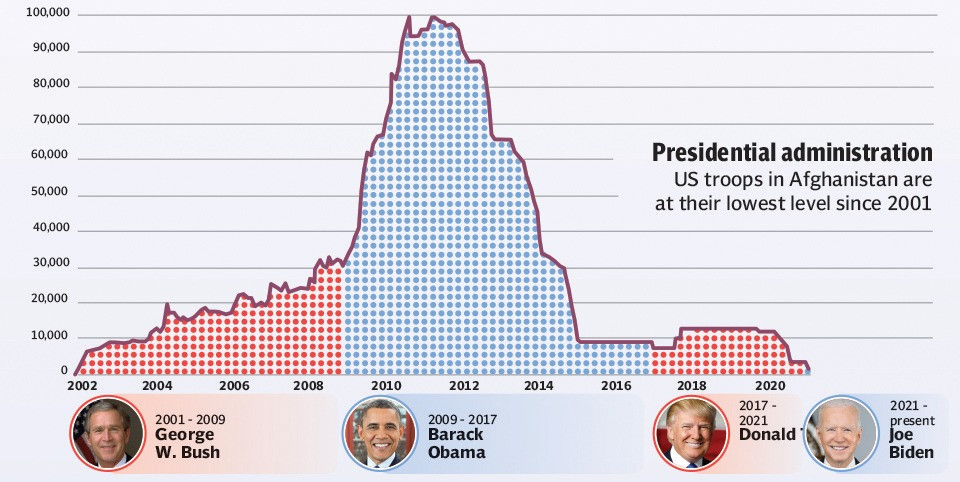

By the time Barack Obama took office, the Taliban had regrouped and gone on the offensive. He blamed his predecessor for losing the focus by launching another war in Iraq. Richard Boucher, assistant secretary of state for south and central Asian affairs between 2006 and 2009, summed up Bush’s Afghan strategy: “We did not know what we were doing.” Obama believed the Bush administration had missed crucial opportunities to win the war. “We could have deployed the full force of American power to hunt down and destroy Osama bin Laden, al Qaeda, the Taliban, and all of the terrorists responsible for 9/11, while supporting real security in Afghanistan,” he said while campaigning for the White House. Once behind the desk in the Oval Office, Obama declared that he had “a clear and focused goal: to disrupt, dismantle and defeat al Qaeda in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and to prevent their return to either country in the future.” In his Afghan strategy, unveiled on March 27, 2009, he further said: “Multiple intelligence estimates have warned that al Qaeda is actively planning attacks on the US homeland from its safe haven in Pakistan. And if the Afghan government falls to the Taliban – or allows al Qaeda to go unchallenged – that country will again be a base for terrorists who want to kill as many of our people as they possibly can.”

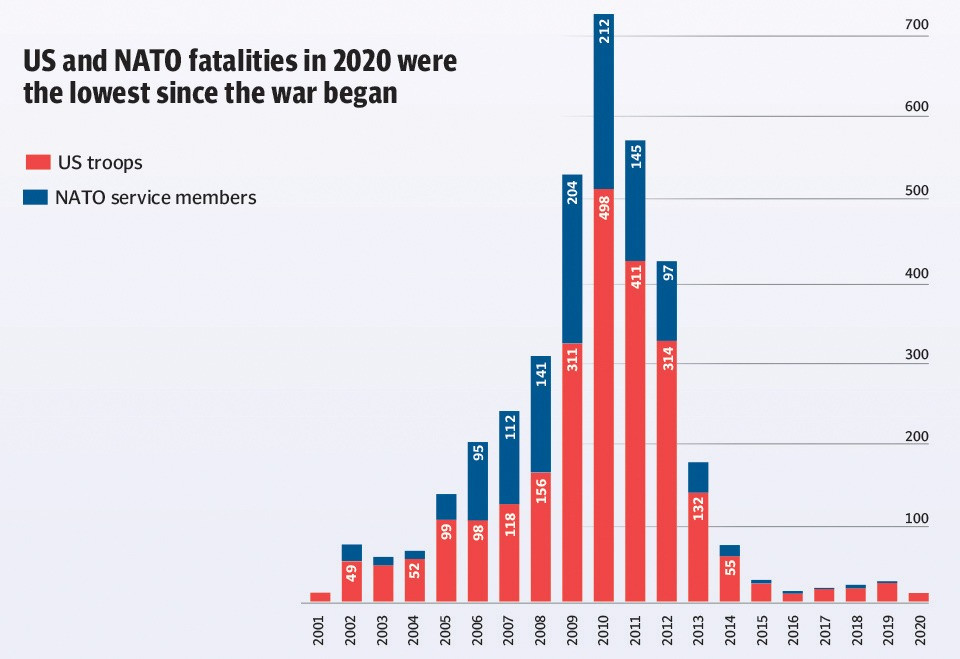

Obama laid out a “clear and focused goal” and a strategy to achieve it. He ordered a massive troop surge to quell the Taliban insurgency. At the same time, he stepped up a highly controversial CIA-led drone campaign in the border regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan to take out al Qaeda and Taliban high value targets. And within a year, al Qaeda was badly crippled, according to the administration officials. “The al Qaeda network has been severely degraded in recent years in efforts that both our countries work on,” US special envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan Richard Holbrooke told a joint news conference with Pakistan’s foreign minister while partially crediting Islamabad for the successes. But the “most significant achievement” came on May 1, 2011 when Bin Laden was killed in a clandestine raid by US special forces in Abbottabad. “We have put al Qaeda on a path to defeat, and we will not relent until the job is done,” he said in a speech on June 22, 2011 in which he also announced his plan to draw down US forces in Afghanistan. “We’ve inflicted serious losses on the Taliban and taken a number of its strongholds.”

And a year later, Obama proudly told the Americans while speaking from Afghanistan’s Bagram airbase: “We broke the Taliban’s momentum. We’ve built strong Afghan security forces. We devastated al Qaeda’s leadership, taking out over 20 of their top 30 leaders. And one year ago, from a base here in Afghanistan, our troops launched the operation that killed Osama bin Laden. The goal that I set – to defeat al Qaeda and deny it a chance to rebuild – is now within our reach.” One more year and Obama described al Qaeda as a “shadow of its former self” which does not pose the kind of threat to America that requires tens of thousands of US troops to fight abroad. “I can announce that over the next year, another 34,000 American troops will come home from Afghanistan. This drawdown will continue. And by the end of next year, our war in Afghanistan will be over,” he said in his State of the Union address on Feb 13, 2013. Obama’s closest ally, British Prime Minister David Cameron, went so far as to claim victory in the war. “The absolute driving part of the [Afghan] mission is a basic level of security so it doesn’t become a haven for terror,” Cameron said on Dec 17, 2013 as he visited the British base in Helmand province. “That is the mission, that was the mission and I think we will have accomplished that mission.”

Despite the hubristic triumphalism, the war in Afghanistan would continue to rage for another nine years. Behind the upbeat veneer, the Obama administration had already swallowed the odious idea of reconciliation with the foe. What he wanted to achieve by upping the ante on the battlefield was to weaken the Taliban’s will to fight and then talk to them from a position of strength. The United States encouraged the Gulf state of Qatar in 2011 to provide an address to the Taliban where American officials would engage them in behind-the-scenes talks. “It took a long time to reach a deal with the US because these [talks] started a few years back during the Obama administration but it was away from the eye of the media so it was only in the time of the Trump administration that we openly talked with them and all the details were told to the media,” Suhail Shaheen, the spokesperson for the Taliban political office in Doha, said in a March 2020 interview after the signing of the US-Taliban deal. President Obama declared cessation of US combat operations in Afghanistan on Dec 28, 2014, excluded the Taliban from future targeting, and announced a major shift in strategy. “We’re no longer in nation-building mode,” he told a meeting of the National Security Council in 2015.

Until then, Obama had frequently bracketed the Taliban with al Qaeda, and beating them was his avowed objective in Afghanistan. But his vice president would say the Taliban were never an enemy of the United States. “There is not a single statement that the president has ever made in any of our policy assertions that the Taliban is our enemy because it threatens US interests,” Joe Biden said in a Dec 2011 interview. But the White House perhaps didn’t know that. “We regard the Taliban as an enemy combatant in a conflict that has been going on, in which the United States has been involved for more than a decade,” Press Secretary Jay Carney said on June 4, 2014 when the militia had freed US Army Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl in return for the release of some top Taliban leaders from Guantanamo Bay. Carney called the Taliban an “enemy combatant” to deflect criticism of Obama for violating America’s sacred policy of not negotiating with terrorists. Perhaps Carney didn’t know that the Taliban were added to the list of Specially Designated Global Terrorists by an executive order in July 2002, while the US National Counterterrorism Center also listed the “Taliban presence in Afghanistan” on its global map of “terrorist groups.”

American military commanders repeatedly claimed “significant progress,” “tangible progress,” and “interesting progress” in the Afghan campaign, but the realisation had sunk in much earlier that it might not be possible to claim mission accomplished. “If we think our exit strategy is to either beat the Taliban – which can’t be done given the local, regional, and cross border circumstances – or to establish an Afghan government that is capable of delivering good government to its citizens using American tools and methods, then we do not have an exit strategy because both of those are impossible,” Richard Boucher said in an unvarnished interview believing it would remain confidential. Obama had set out to win the war in Afghanistan but ended up joining the initiative to reconcile the enemy.

Speculations were rife that his successor, Donald Trump, would pull the plug on the war he had called “futile” while campaigning for the White House. But he didn’t. “My original instinct was to pull out, and historically I like following my instincts,” he said in a speech to troops at Fort Myer, Virginia, on Aug 21, 2017. “But all my life, I’ve heard that decisions are much different when you sit behind the desk in the Oval Office,” Trump said. After exhaustive deliberations with his war cabinet he had been convinced that “a hasty withdrawal would create a vacuum for terrorists, including ISIS and al Qaeda,” he added. “The men and women who serve our nation in combat deserve a plan for victory. They deserve the tools they need, and the trust they have earned, to fight and to win.” Thus began a pursuit that his predecessors had to give up.

Trump said he would increase US military deployment in Afghanistan and ratchet up pressure on Pakistan to shut the “terrorist sanctuaries” on its western border. The duration and objective of the new deployment wasn’t clear. He sought to portray his strategy as a stark break with the Obama administration. But in essence, it wasn’t. The only difference was Trump’s imperial bellicosity and hubristic disdain for the enemy that he referred to as thugs, criminals, predators, and losers. “The killers need to know that they have nowhere to hide, that no place is beyond the reach of American might and American arms,” Trump said in the policy speech. “Retribution will be fast and powerful,” he added. “We are not nation-building again. We are killing terrorists.”

Little did Trump know that three years later he would be happy to call up the deputy chief of the same thugs and losers and compliment them as a “tough people” with a “very good country”! “I know that you are fighting for your soil. We have been there for 19 years and that's a long period. Now, the withdrawal of foreign forces from Afghanistan is in everyone’s favour,” Trump told Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar over the phone in March 2020.

However, Trump’s tryst with the Taliban was as mercurial as his temper. The on-again, off-again process continued for a couple of years. And just as a deal was in plain sight, Trump abruptly called off a secret Camp David meeting with the Taliban deputy chief and the Afghan president, and ramped up war rhetoric instead. “We have been serving as policemen in Afghanistan, and that was not meant to be the job of our great soldiers, the finest on earth,” he wrote in a super-hyperbolic tweet in Sept 2019. “Over the last four days, we have been hitting our enemy harder than at any time in the last ten years!” Trump called the Taliban “enemy” in a stark reversal from the Obama-era position.

Despite his bellicose talk, Trump was convinced about the futility of war in Afghanistan. He knew that the use of more military force would only sink the US deeper into a quagmire he desperately wanted to extricate himself from. The chief US negotiator, Zalmay Khalilzad, salvaged the peace initiative. And on Feb 29, 2020, the Trump administration signed an agreement with the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan”, the name the Taliban use for their government-in-waiting. Critics said this was akin to recognising the Taliban as a parallel government and eroding legitimacy of the democratically elected government in Kabul. But Trump was happy to have pulled off something his predecessors had failed to deliver. “Other [US] presidents have tried and they have been unable to get any kind of an agreement,” Trump said after the phone call to Mullah Baradar, which came three days after the Doha signing.

The deal envisaged all US troops out of Afghanistan by May 1, 2021 [the process started immediately] in return for a Taliban assurance they would not allow al Qaeda or any other terror group to use the areas they control. The US troops had been killing terrorists in Afghanistan “by the thousands” and now it was “time for someone else to do that work and it will be the Taliban and it could be surrounding countries”, Trump said assigning the role of US forces to the Taliban. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who attended the Doha signing as a witness, defended the deal and described al Qaeda as a “shadow of its former self” borrowing a phrase from Obama to portray the global terror network as more of a nuisance.

From Bush to Biden, every administration has claimed that al Qaeda in Afghanistan has been devastated, and poses no serious threat to America. But the Pentagon doesn’t appear to be in agreement with this optimistic assessment. US Centcom chief General Kenneth F McKenzie warned during a recent Pentagon briefing that after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, the biggest threat would be regrouping of al Qaeda and ISIS militants who “will be able to regenerate if pressure is not kept on them”. He apparently sought a military base in one of Afghanistan’s neighbouring countries to keep the Taliban in check. Months before Gen McKenzie, the fear was expressed by Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg. “Afghanistan risks becoming once again a platform for international terrorists to plan and organise attacks on our homelands,” he said in Sept 2020, soon after the US started scaling down troops following the Doha deal. “And ISIS could rebuild in Afghanistan the terror caliphate it lost in Syria and Iraq.”

These bleak military assessments mean the Americans might be in for a rude awakening in Afghanistan because: a.) the gains of two decades of military campaign against al Qaeda are so fragile they could unravel soon after the exit of foreign forces; b.) the Taliban are strong enough to retake the country; and c.) the multibillion-dollar project to build a Western-style democracy might be an exercise in futility because the Taliban reject the Afghan constitution and want a theocratic state based on political Islam.

If a ‘modicum of success’ is all the US military could tout after years of ‘strategic stalemate’ in the trillion dollar war in Afghanistan, then America needs to ask itself if the two-decade campaign was worth its price in blood and treasure.