Pandemic pains: the plight of Pakistan’s labourers

Pakistan’s labourers struggle to make ends meet as coronavirus pushes them beyond the edge of insecurity

KARACHI:It was over a century ago that a violent struggle between labour protesters and the police in Chicago struck so deep a chord with people that it forever became a symbol of struggle of the rights of the labourers. So profoundly did the protest that transformed into a bloody shootout (where there were both police and civilian casualties) elevate the plight of labourers that the month of May will forever be remembered for them.

Creative: Mohsin Alam

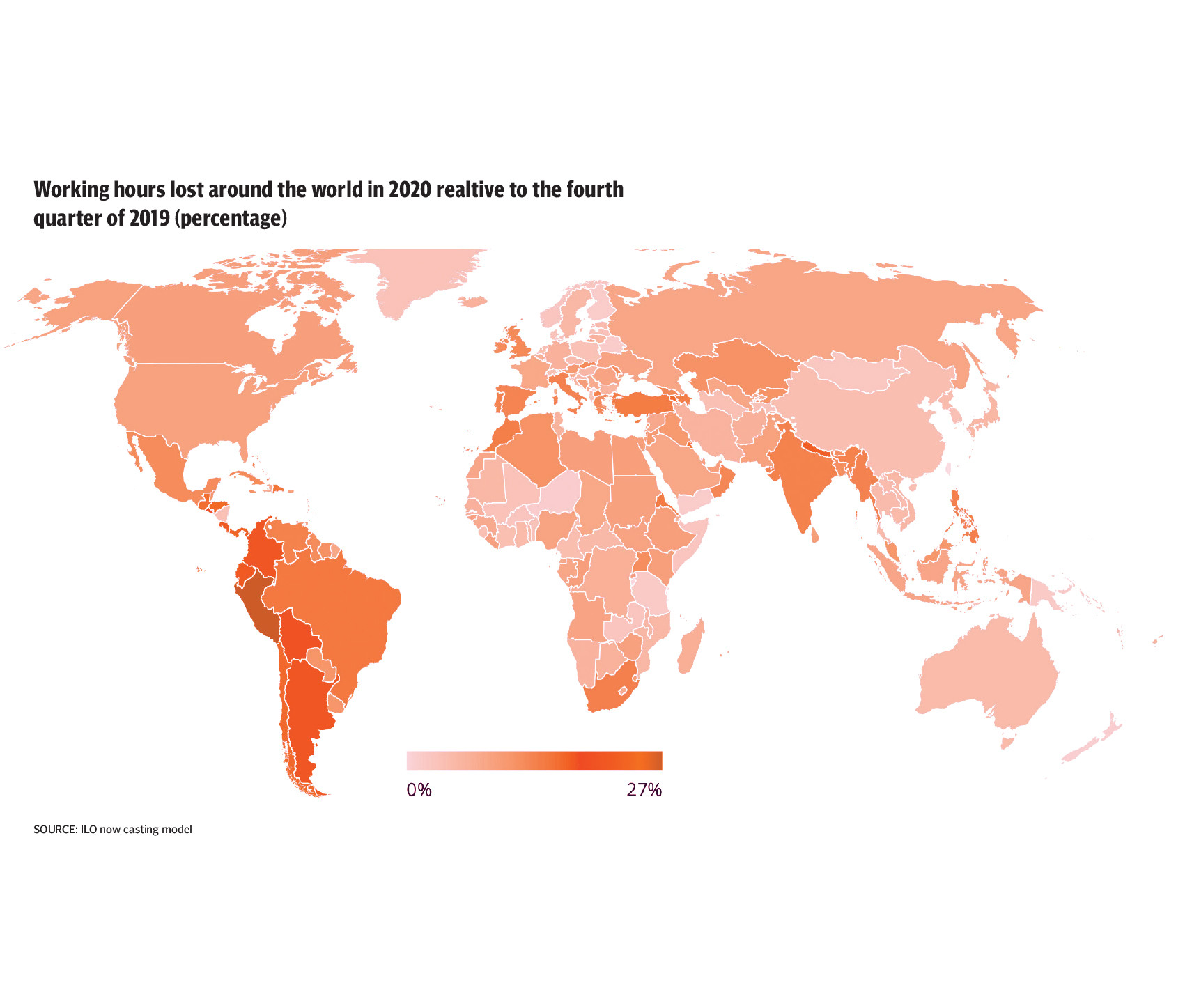

The labour class in Pakistan has always been on the brink of unemployment. One injury or dismissal can push them to homelessness and starvation. The coronavirus pandemic which spread across the globe like a wildfire, showing neither prejudice nor mercy in selecting its victims, hit the labour force in impoverished nations in a way that has left many of them unable to make ends meet.

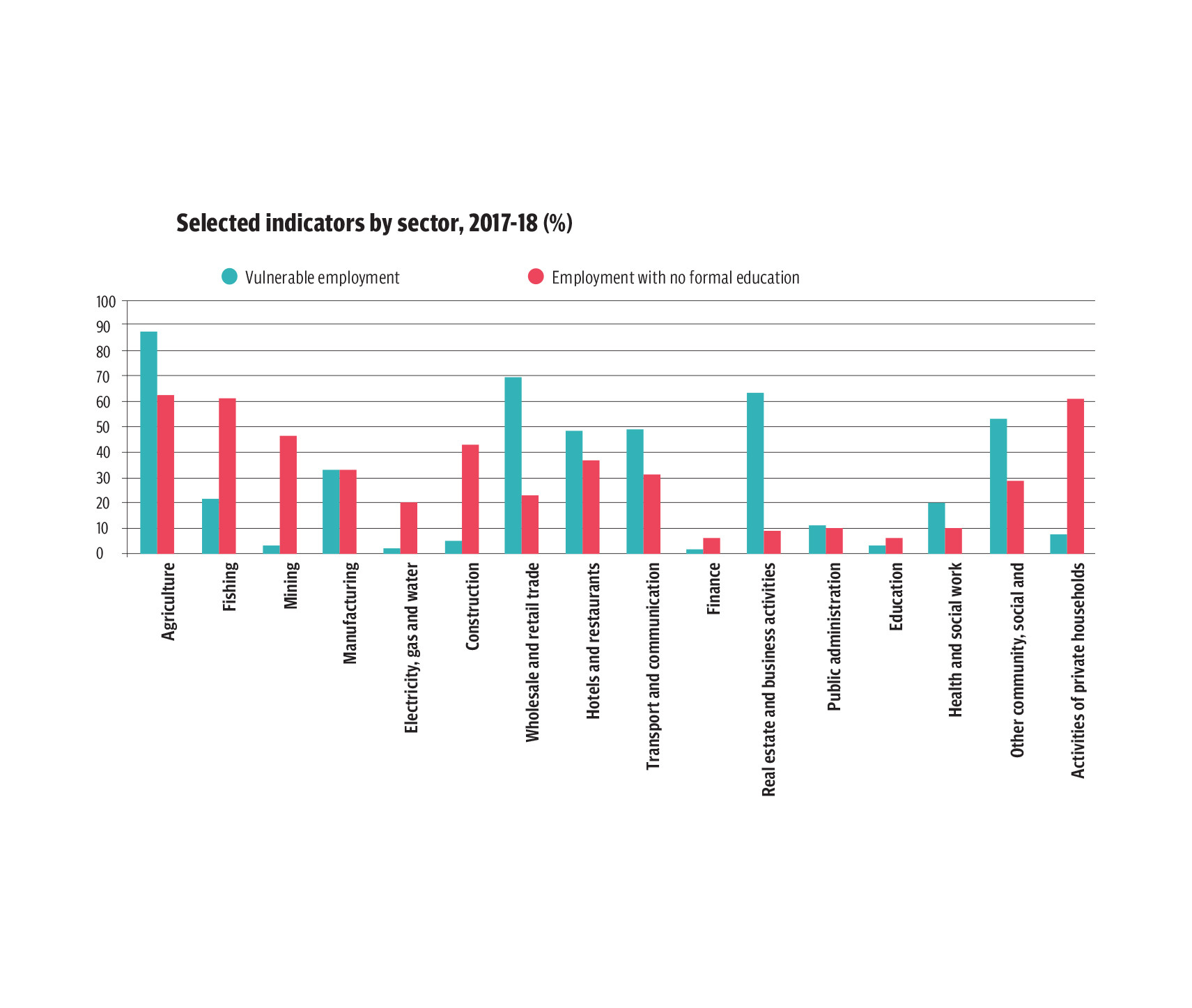

According to a 2018 Labour Force Survey by Pakistan Bureau of Statistics titled, ‘Pakistan Employment Trends,’ the unemployment rate for both sexes was before the pandemic was already at 5.1% between 2017 and 2018. The share of employment in agriculture working 50 hours or more had also declined from 29.3 per cent between 2006 and 2007 to 23.7 per cent between 2017 and 2018.

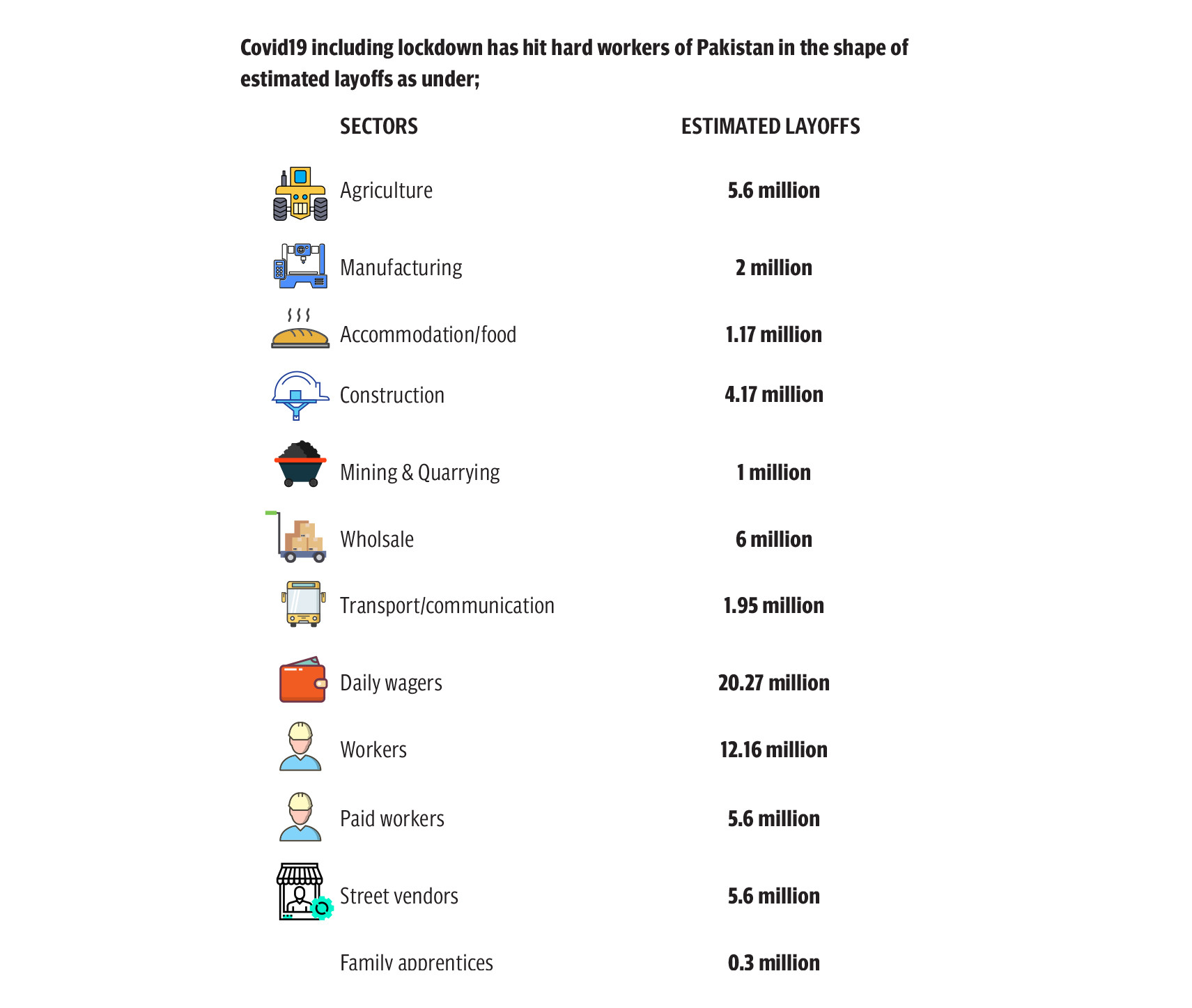

According to a paper titled, Covid-19 and World of Work, by Pakistan Worker’s Federation that assessed the impact of the pandemic on the workforce between 20th March, 2020 and 20th May, 2020 estimated layoffs by mid-May 2020 had reached 5.6 million in agriculture, 2 million in manufacturing, 1.17 million in accommodation and food, 4.17 million in construction, 1 million in mining and quarrying, 6 million in wholesale, 1.95 million in transport and communication, 20.27 million in daily wagers.

More than ten thousand power loom workers alone in Faisalabad have lost their jobs and hundreds of thousand brick kiln workers in the Punjab province alone have lost their livelihood. Textile industries in Pakistan also had to conduct layoffs, especially those industries whose export were cancelled due to the pandemic. In Balochistan, 30 per cent of mine workers also lost their jobs.

According to the International Labour Organisation database, Pakistan’s unemployment rate, which was already 3.98 per cent in 2019, increased to 4.65 per cent in 2020. Now with the third wave of the deadly pandemic sweeping across the nation, the labour force fears that the worst us yet to come.

“There even came a time when I thought to leave everything and go back to my village and start farming,” shared Aslam Khan* who works at Gadani ship-breaking yard and was unable to earn his living during the lockdown. The story of Khan, however, is no different from many others living in the area as almost every household in the vicinity is suffering from more or less from the same problems.

“The workload had already been slowing down since 2018, when dollar prices started to increase. Out of several work setups, hardly one to two were working because no ships were coming to the breaking yard,” said the ship breaking workers union head, Bashir Mehmoodani. The most affected social class was the poor labor class, which was left with no choice other than to move back to their villages or wait for government help. “After two months of strict lockdown, the union started helping the poor people. A few NGOs came out to help as well but that was not sufficient as it was a temporary solution to the bigger problem,” he said, adding that those two months impacted the economy very severely and that it can take years to come back to just the level of stability.

The breaking yard houses approximately 500 families in Gadani where the workers do not have to pay rent however, other basic facilities are not sufficient there. “In 24 hours, we only get electricity for three to four hours so if even the government announced relaxation in electricity bills what we would have get from that in the end?” said Khan, who has a family of five members, including his two toddlers. Gadani is not only is deprived of necessities like electricity but also water supply is also huge issue and leaves the residents with no other choice but to resort to buying water, which automatically increases the expenses of the labor class. “Living here is free as the land is not, we pay for but electricity and water take away all of what we earn,” he shared.

The normal wage for any labour working at the breaking yard is between Rs8,000 and 9,000 for a junior labour for 15 days of work and the amount goes upto Rs 15,000 to 20,000 for a senior welder for the same time period.

Daily-wage woes

“Two to three times during this situation last year, I didn’t go back to my home as I hadn’t earned anything and I knew my hungry children were waiting for me at home,” shared Ismail Shah, who lives in a make-shift settlement which he calls home. Shah who works as a labourer at construction sites was unable to earn a living after the construction ceased completely during the last lockdown. “There were days when people used to give us donations but after a while, even that stopped because times were tough for everyone, and every business and person was affected in one way or another.”

Last year when the country was closed down and since then the timing of the markets and the workplaces were fluctuating, the businesses and markets also suffered and more than that the labourers working in those markets were directly affected. “No one can pay the salaries of the labour for long because the business is shut and the even the owners are unable to pay the rents,” said Chairman Al Karachi Tajir Ittehad Ateeq Mir, while talking to The Express Tribune. He also shared how there was no income and shop owners were even unable to pay electricity bills. Answering if the government promised relaxations were given to the businesses, he said, “Relaxation in electricity bills was not even close to what is relaxation is. The owners who have big setups were still in a better position to pay to their workers but shopkeepers who were already living hand to mouth, how could they have done so?” he said, adding that a lot of people shut their businesses because they were unable to pay their shop rents, employee salaries and utility bills and the workers working for them also lost their jobs in the process.

“There are countries which are still fighting it and are sustaining but we (Pakistan) can’t sustain if we close down everything,” said the chairman reasoning that our governments can’t compensate for the loss we are facing, and if this continues the economy of the country cannot be brought back.

To curb the misery, the State Bank of Pakistan launched a three types of loan schemes to help businesses sustain themselves. Through these loans, they can pay their bills, salaries, and rent but many people chose against taking them the mark-up from those loans would have only added to their burdens during these uncertain times. According to Mir, “The most affected from the lockdown is not the lower social class worker but the lower middle class who do not register themselves in any charity and donation drives and do not even ask for money. The white-collared workers are the ones who did not get any compensation whereas the lower class was still receiving donations, most of them even received the Ehsaas programme money,” he added.

An invisible struggle

The struggles of home-based women workers invisible to our eyes as they’re hidden in inside their homes. Working day and night for a miniscule minimum wage while also managing house chores and raising kids is not an easy task and when Covid-19 hit, these women lost a lot of work too.

“I attach small mirrors to stoles and sometimes we just attach them to laces for a mere of three rupees per metre,” said Shahida, who lives in Korangi, while showing small triangular mirrors which she was sticking to a scarf with a glue gun. Shahida and almost every woman in her area work for such vendors who bring them work like this. “These are one-off jobs usually. Sometimes we attach pins to hairbrushes, cut off extra threads from jeans or even stitch pockets,” she said. The women are able to secure such work based on their skills. For example, if someone knows how to stitch, then they earn better as they stitch whole dresses but ones who aren’t able to do that, can secure other odd jobs such as Shahida. Those who can stitch can earn Rs 15 to 25 for a child’s dress.

The market and businesses mostly exploit workers as they are unaware of their rights and also are needy and with the given situation of Covid-19 and lockdown, home-based workers suffered a lot with companies either completely shutting down or going to half working capacities. Even the men of the houses losing their jobs so the women of the lower social class were helpless in the case and worked tirelessly for the whole day for a mere Rs100 or Rs200.

Such home-based workers are usually catered by a contractor or a supervisor who picks work from companies and distributes it to the low-income areas where women are desperately in need to make extra money without leaving their homes, so they agree to the jobs on very minimal amounts. “I get work through a man who has contacts in textile companies who outsource their work and here I provide him services for my area,” said Kanwal Faheem, who distributes work to women like Shahida. As a woman, she has access to these households since factory managers cannot approach these women directly. Moreover, with one person managing an area, the rates can be taken care of or else each house can keep quoting different rates which may become too chaotic to manage.

Sharing how Covid-19 and lockdown have impacted their work, Kanwal shared that last year when markets were closed, it was difficult for every one of us as most of the men here are daily wagers or workers in factories and most of them lost their jobs and even women weren’t getting the work so people were struggling to make ends meet. “Now since the markets have partially opened, even with specific timings, factories have started producing and people have started getting work,” she shared adding that they are hopeful that there will not be any lockdown now but yes specific days and timings will slow down the work but still they are thankful that at last, they are getting work.

Laid off with no warning

Labourers in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the majority of whom are employed in agriculture and work for daily wages, faced similar struggles as the rest of the country.

Sarir Khan, who is a painter by profession, told The Express Tribune that he earns about Rs 1,500 a day when he is contracted work while his household expenses stand at Rs1,000 a day. He has a wife and two children to support at home, who impatiently wait for him to bring essentials and food when he returns from work. “During the first lockdown, there were days when people had to go home empty-handed,” said Khan. “People used to run away due to fear of the virus during the first wave of Covid-19 and I was even forced to work at the vegetable market to make ends meet.”

An employee named Faisal Shehzad based in Peshawar, who works in a private company, maintained that during the 2020 lockdown, he was sent on compulsory leave by the company. A few days later, he received a call asking him to come and collect his salary. When he went to collect his salary, he was told that he had been fired. He said that there were no jobs due to the lockdown and he ran from pillar to post in search of a job for four months but found no success. Now he has finally secured work at a factory but still fears of imposition of a lockdown.

The Express Tribune tried to contact Provincial Minister for Labour Shaukat Yousafzai and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government’s spokesperson Kamran Bangash for a comment but despite several attempts, they could not be reached.

Balochistan Labour Federation President Khan Zaman has said that till date the ratio of daily wagers unemployed by Covid-19 across Balochistan is almost 50,000 with 25,000 out-of-work labourers in District Lasbela alone.

According to Zaman, nearly 500,000 daily wagers are in Balochistan alone.

According to General Secretary Workers Federation Peer Mohammad Kakar Pakistan, during the pandemic, the daily wagers who work as domestic workers were 100 per cent unemployed last year but now it’s again reaching around 70 per cent in Balochistan because of the third wave of the virus.

“It takes me slightly over an hour to reach my workplace daily on foot and this is third day I am going home with empty hands due to prevailing situation,” said a fifty-year-old labour Muhammad Irfan. “My forefathers were also engaged in this work but we never experienced this situation at our homes before.”

Similarly, the third wave of coronavirus has affected a large number of daily wage earners in Punjab too. Strict enforcement of SOPs in factories and mandatory condition to restrict staff attendance to 50 per cent has led several industrial workers redundant. Altogether, this vulnerable class of workers represents around 20 per cent of the entire labour force of the province, according to a conservative estimate.

Iftikhar, a daily wage worker and a hard laborer engaged in Gulberg main market, told The Express Tribune that he used to work as a construction worker would be paid Rs 1,200 a day but because people have stopped contracting for him work now.

Similarly, Ali, who works in a restaurant, said that since the ban on outdoor and indoor dining, he has also been laid off. He used to earn between Rs600 to 700 a day but now he is forced to remain at home without a penny to call is livelihood.

(THIS ARTICLE INCLUDES ADDITIONAL REPORTING BY MUHAMMAD ILYAS FROM LAHORE, AHTESHAM BASHIR FROM PESHAWAR AND ZAFAR BALOCH FROM QUETTA)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ