On breathing words

The Covid-19 pandemic provides us a catalyst to appreciate human helplessness

It is almost a year now since a tiny virus that put our lives upside down first ambushed us. As all our hopes to return to a normal life retreat further and farther into the future, in a certain uncertainty we are floating desperately in this troubled air that surrounds us. Some of us have already lost their loving family members and friends, but then there are those who have survived and are trying to cope with the long term effect of this virus we call Covid-19: the so-called post Covid syndrome, along with many other symptoms like shortness of breath. In many ways, this pandemic has provided us a catalyst to understand many aspects of human helplessness and also courage in front of the catastrophe and we visit and revisit literature that has shaped various modes to understand and experience the disease.

This instance has provided us yet another opportunity to talk about the overall human condition vis à vis diseases at general – both in our day-to-day life and in our literature. A formidable number of literary works touching on Covid-19 have been already produced in different parts of the world – poetry, fiction, non-fiction and even critical accounts that discuss and assess this body of literature. Our own literature has been quite alive to this representation. Taking the line of discussion a little further, one would like to muse on a lesser menacing and a not-too-precarious illness that could otherwise – in tandem with Covid-19 – reach to a malignant magnitude, that is, asthma.

This is important also for the fact that the new pandemic revokes some old metaphors into life, for example, breath and breathing, and it reminds us to take a pause and introspect the fragility of life in the seemingly mundane experiences rather than letting them blur into a miasma of disjointed and scattered images.

Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib breathed his last on February 15, 1869. PHOTO: FILE

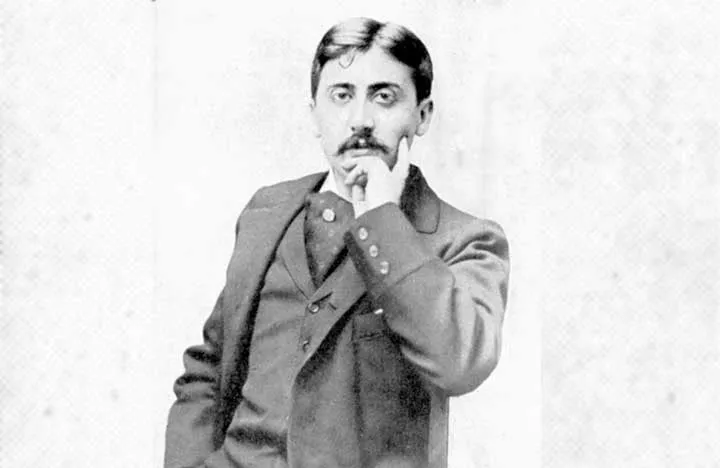

The moment I was diagnosed with asthma caused by multiple types of allergies – from pollen to dust mite – that create, at times, constant respiratory problems, I recalled Marcel Proust who “was subject from the age of nine to violent attacks of asthma,” as one of his biographers tells us, “and although he did a year of military service as a young man and studied law and political science, his invalidism disqualified him from an active professional life.”

Well, Proust was ‘distinctly asthmatic’, but that is the story of his personal life whereas here we are more interested in the novel he wrote and through which Proust – the man – continues to live even centuries after his death: In Search of Lost Time. Portrayal of the disease, in one section of the book, goes like this:

“There are asthma sufferers who can assuage their attacks only by opening the windows, inhaling the high winds, the pure air of mountains, others by taking refuge in the heart of the city, in a smoke-filled room….”

There is another character that even the smell of the sardine fisheries gives him “terrible attacks of asthma.”

But, how to draw a dividing line between the story of the man and story of the writer, especially when the novel comes out in the first-person narration and it has a lot of autobiographical elements in it?

In any event, we know that Proust’s asthma was repeatedly triggered by allergies - especially to certain plants and scents. He confided in a friend that he would have a fit just by looking at the painting of a rose, and that certain women – because of their strong perfume – were not allowed into his apartment.

Thinking of Proust’s pulmonary pathophysiological problems is not in the vein of a self-flattering megalomania cherished through identifying oneself with the great writer; rather it may be taken as an attempt to seek relief from the high literature – even in the matters of one’s health. It is not even an instance of Schadenfreude, the feeling of gloating over the malady-ridden writer; it could, however, be considered as an act of experiencing an empathy with him and deriving, maybe, some amount of masochism that Proust himself might have gone through while narrating his misery.

Respiratory problems cause excessive phlegm in the lungs that results in chest congestion, my doctor tells me. Cold air also creates problems as your airways are irritated and swollen by it, he adds.

Our poet Ghalib, however, comes with a panacea to all such ills:

Pii, Jis Qadar Mile, Shab-e-Mahtaab MeN Sharaab!

Is Balghami Mizaaj ko Garmii Hii Raas Hay

(Drink as much of wine as you come by in the moonlit night!

It's the heat only that suits your phlegmatic temperament.)

Well, Ghalib was a watery phlegmatic and I of the airy sanguine temperament, so, simple wine can be of little use in my case.

Proust’s allergy to scents inadvertently draws our attention to another Urdu poet, Firaq Gorakhpuri. To relate a story from the horse’s mouth: our poet in his infancy or early childhood was allergic to going into the laps of, let’s put it in milder terms, not so beautiful women; in the hands of fairer ladies, on the other hand, he would be quite comfortable.

So, allergies here, in contradistinction to the ones that afflicted Proust, have got altogether different dimensions – albeit all three types have aesthetic criteria in their reaction and response. Persian poet Sa'eb Tabrizi had, as most of the genuine literary lot would do, an acute allergy to his fellow human beings. But, we are not supposed to go too far – to the metaphoric or symbolic allergies, and better we confine ourselves to the ones that tend to suffocate us in the true sense of the verb.

Having allergies or having no allergies, the vital point is that of the breath; of breathing – the dialectics of breathing in and breathing out that one of our classical poet, Meer Dard, had called Namaaz e Ahhl-e-Hayaat; an obligatory prayer of the living beings, that one must never miss as when it is missed, one misses the train to life.

Asthma, as we all know, is a health problem related to respiration. The Urdu word Dama that derives from Dam (breath) conveys this relationship with the disease more explicitly. Dam is used also as prefix and, in some cases, also a suffix like in Ham-Dam. Here Ham a prefix: ‘Co-’ in English, and Dam stands for breath as well as the current moment. Generally, a Ham-Dam is a close companion, but it may be the one who lives in the same moment and inhales from/shares the same pool of breathing air.

We have another cognate, a compound – Ham-Nafas, wherein Nafas again means a breath. Both Ham-Dam and Ham-Nafas have the same compound construction and almost similar meanings, but whereas the latter has an air of classic about it, the former has been, by and large, relegated to somewhat kitsch category. That said, comrade, colleague, and confidante – name you any word and none of them would come to level of the subtle and profound layers that Ham-Nafas and Ham-Dam offer. So, a simple paraphrasing of these compound words can hardly convey the deep shades they carry. They both suggest also someone who is close to your breaths – whose breaths intermingle with those of yours – conveying thereby not only a sense of proximity and intimacy but also of a relation vital as breath and breathing itself and so on.

Both words appear frequently in Persian and Urdu poetry in varied contexts and with variegated connotations. Dama, per say, however, does not occur very often in our poetry. Instead, our poets tended to refer to other verbal coinages that might signify the malady, but their semantic range would be much wider. Indian-Persian poet, Bedil Dehlavi, for example, employs Nafas-Tangi, that literally is: a restriction in breathing.

Asthma might not be as such a lethal disease, but surely, it could be generative to different fatal maladies. It is a life-long ailment, as a proverb suggests it – Dama, Dam Ke Sath and Aadmi Gham Saath (Asthma, when it is started, it accompanies you till your last breath. Similarly, sorrow is inalienably attached to the human being). It is a disease that is not only annoying and irritating, but it is also the one that disturbs the very basic rhythm of your life. Naturally, you have to bear with it and in this process of coming in terms with it you learn, though intuitively, some deeper meanings and latent layers of the disease. While writing these lines I was pleasantly surprised to note that over the period of last few years certain respiratory issues have already sneaked into my own poetry.

Woh Habs – e Jaan Hay Ke Seene MeN Saans Ulajhne Lagi

So, AAj Dard e FaraawaaN Bhii Pay-Ba-Pay Naheen Hay

(Such life-choking the suffocation is that breaths entangle within the chest

So, today even the abundant pain is not so incessant)

or

Aisa Safar Ke Seene MeN Urtii Thii Dhool Sii

Phir Saans Ko Bahaal Kiaa Aur Chal Pare

(What a journey it was that a dust-storm brewed in my chest

And I restored my breath and proceeded)

Need not to say, it is not only an asthmatic who can write about such matters. Theoretically, anybody can write about anything. On having pestered with non-stop speculations about the identity of the female protagonist in his novel Madame Bovary, Gustave Flaubert had famously exclaimed: “Madame Bovary, c'est moi” (I am Madame Bovary). Nevertheless, one must not take Flaubert’s statement too literally as the novelist is doing here nothing but to assert that he has understood the character intimately and has portrayed it truthfully. It matters little that the subject matter you come with has been your Erlebnis – the lived experience, or not; important is the end result, the finished form of your literary artefact.

Thomas Mann was of the opinion: “All interest in disease and death is only another expression of interest in life.”

A malady, ‘the night-side of life’ – to remember a telling phrase of Susan Sontag – can provide an impulse to think about and put forward some vital issues in your writings.

Interestingly, the word ‘inspiration’ also relates to the semantic cast of the breath as we all know that it comes from Latin verb inspirare: ‘breathe or blow into’. The word was originally used of a divine or supernatural being, in the sense of ‘impart a truth or idea to someone’.

Can some sort of inspiration be of any help in mending the deteriorated condition of respiration as well? I don't know, but I hope so and believe that one must always be optimistic and be longing for the Muses - till one expires, till one breathes one’s last.

(The writer is a Pakistan-born and Austria-based poet in Urdu and English. He teaches South Asian Literature & Culture at Vienna University)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ