Taliban seek image revamp as peace talks grind on

Social media messages, videos, website reports aim at depicting militia as good governors

As Afghan peace talks grind on, the Taliban are trying to portray themselves as a viable government-in-waiting in an image makeover that includes rehabilitating their ultra-violent affiliate, the Haqqani network.

Negotiators from both sides in Afghanistan’s 19-year-old war have been meeting in Qatar since September and are attempting to draw up a blueprint for the country after US and foreign forces leave next year. However, the languid pace of talks belies the chaos on the ground in Afghanistan.

As the militants push for battlefield dominance including a major assault this month in Helmand province, the Taliban’s propaganda arm is churning out a steady stream of social media messages and videos, and publishing reports on a slick website depicting themselves as good governors.

A recent article said Taliban task forces had been deployed in Kabul to protect the population against “lawlessness and corruption”. A video released on Facebook by the group this year showed members in surgical masks distributing hand sanitisers after the coronavirus reached Afghanistan.

And even though they frequently blow up telecom towers and government buildings, the militants are also circulating claims on WhatsApp about their infrastructure projects such as roads and irrigation canals. Sediq Sediqqi, a spokesman for President Ashraf Ghani, highlighted this apparent contradiction.

“On one hand, they are talking about brotherhood, mercy, service, humility, and unity, and affection among the Muslims,” Sediqqi told AFP. “And on the other hand, they are killing and wounding innocent civilians, including women and children.”

The most dramatic part of the Taliban’s public relations push is around the Haqqani network. Designated a foreign terrorist group by the US State Department in 2012, the network has been linked to a string of attacks against foreign forces and Afghan civilians.

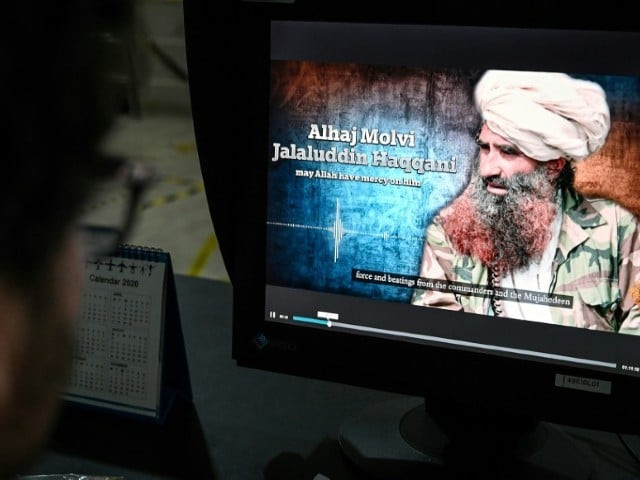

A new documentary tracing the life of Jalaluddin Haqqani, founder of the eponymous network, depicts him as a “great reformer”, who fought heroically over four decades – first against the Soviets and then against the Americans.

The film features archive footage of the bearded and turbaned Haqqani, who died in 2018, and claims he was an effective administrator in his former stronghold of Khost province, where he opened dozens of madrassas, “focused on charity” and fought corruption.

Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid said the film aimed to “introduce” Haqqani as an “icon”. “We wanted to show his way of life, his sacrifices, his speeches to our future leaders and young mujahideen,” he told AFP.

The film seeks to rebrand the deadly and once semi-autonomous Haqqani network, and present them as unified with the broader Taliban movement, Andrew Watkins, an analyst on Afghanistan for the Crisis Group think tank, told AFP.

The Taliban “clearly have an agenda” to show supporters and outside audiences that the two groups “are the same thing”. “They may not have been in the past but they are today. And the Taliban celebrating the Haqqani network’s patriarch is a way of solidifying that,” Watkins said.

In February, Sirajuddin Haqqani, one of Haqqani’s sons who now heads the Haqqani network and is also deputy leader of the Taliban, penned an editorial in The New York Times. Sirajuddin wrote that the Taliban were ready to agree to “a new, inclusive political system in which the voice of every Afghan is reflected and where no Afghan feels excluded”.

The Taliban’s attempt to depict themselves and the Haqqanis as efficient rulers is a far cry from early public relations efforts, when the insurgents produced videos, showing suicide bombers. Watkins said the effort being pumped into the image revamp is directly linked to the peace talks: “They’ve expanded their capability and are producing on a staggering scale now.”

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ