Creating art out of bricks

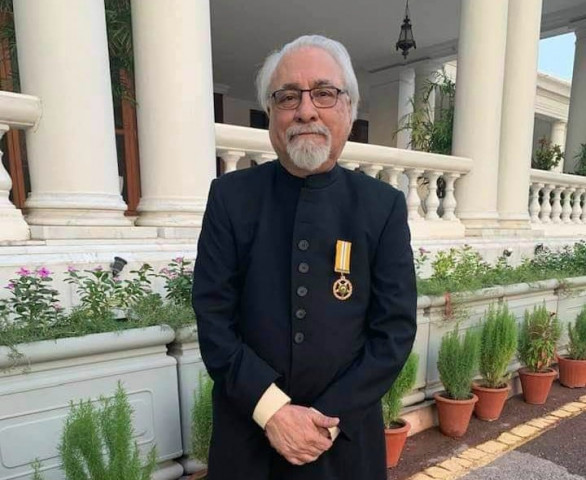

2020 Tamgha-i-Imtiaz recipient Naeem Pasha talks about navigating architectural masterpieces

One of the most prominent architects of Pakistan, Naeem Pasha, also the recipient of the 2020 Tamgha-i-Imtiaz, is a bit of a chameleon – his artistic expression manifests in several mediums and in multiple ways. Besides holding the distinction of being one of the most eminent architects of the country, Pasha is a prolific painter, curator, interior designer, poet and social pundit.

He started painting at a young age and in his youthful naivety, he thought that Rembrandt was the easiest to copy.

“Just before my middle exams, I had a knee injury that got bad and I was lying on the sofa most of the time. One day, my brother quizzed me about my plans for the future and I mentioned me wanting to be an architect. He laughed it off and warned me that I will end up with grey hair and thick glasses like all the other architects,” he shares, adding how at the time, there were no colleges offering a degree in architecture and his family couldn’t afford a foreign education either.

Pasha landed at NCA in 1960 but two years in, he left to join the University of Engineering and Technology - NCA only offered a diploma but the university offered a degree. “Whatever little natural talent I had in art got furthered at NCA as most of my evenings were spent there. There were very few students in the college so I could walk into any studio and watch the class do the work.”

“Sometimes I would stand on the upper floor at the university looking at the labourers below constructing some new blocks. I would draw them from a top view but for some odd reason they appeared elongated in my sketches as if I was looking at them from below,” Pasha explains, talking about how he developed his strength of perfecting proportion. “That perspective became very interesting and gave me some innovative ideas on proportions and how to deconstruct objects,” he reflects.

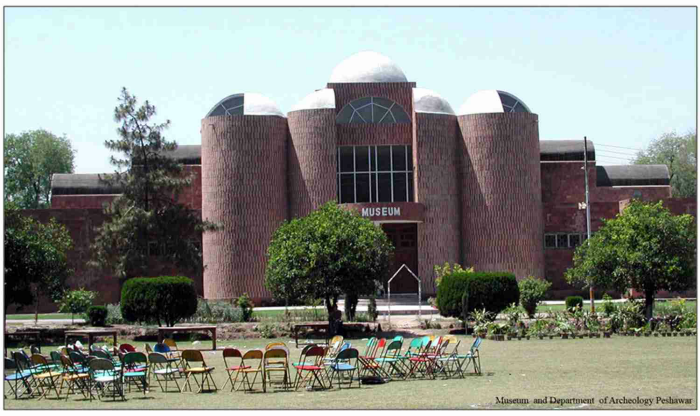

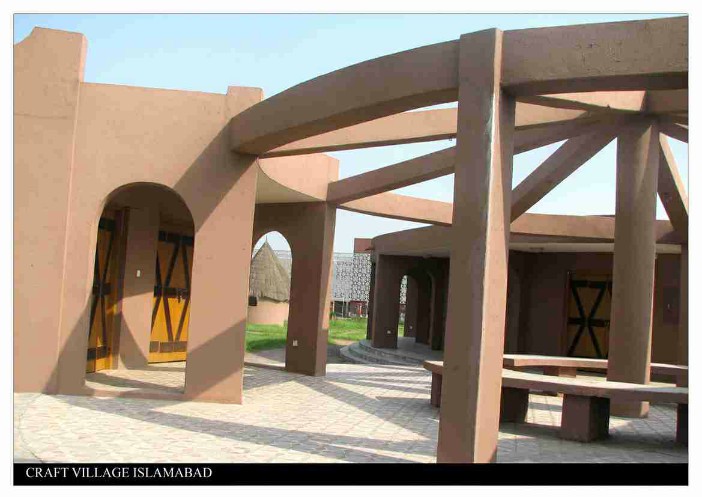

After graduating in 1967, he started designing buildings and has landmark buildings such as the Museum and Department of Archaeology, Peshawar; State Life Tower, Islamabad; PAF Academy, Risalpur; and Art and Craft Village, Islamabad under his belt.

Pasha also has the honour of designing the National Art Gallery, Islamabad, and one thing that stands out in his designs is his variety of inspirations that are generally aligned with the functional purpose of the building.

When Prince Charles visited Pakistan, he was invited to meet the royal guest. Pasha recalls the Prince being concerned about an extension planned to the main building and how that may compromise the original Denise Scott Brown design. “He was obviously very with the tradition so I explained to him that even in the initial design one could see traces of Alhambra and Granada because British also didn’t just do British Gingerbread House but brought Greko-Roman with the traditions of grandeur, stability, agility, and royalty in architecture.”

“My first project was to build a house in Multan for the Gardezi family. They brought their family mason to work with me and though I knew my business, I didn’t know anything about construction apart from what I had seen at a project site,” he recalls, sharing how he learned from these masons along the way and still uses their advice over his own foresight.

“I was designing a dog legged staircase and I was not leaving enough space between and the two railings were cutting into each other. Thankfully the mason was there and he proposed minor alterations and we fixed it. Even today if a mason tells me what to do I am more than willing to listen to him,” Pasha admits.

Talking about his own style of architecture, Pasha feels that should be something that evolves unconsciously and subconsciously. “If someone sees a building and says this looks like Pasha’s design then they are defining a certain style for me.”

Pasha believes that building should always be designed from inside out but a lot of times architects make an envelope and try to fit their function in it. Pasha considers Louis Isadore Kahn as a teacher although having never met him. “Kahn says we must go looking for the whole and once we know the whole then go looking for the pieces,” he explains.

“If we start by putting together pieces we will never make a whole. But while evolving an idea, always have a certain scale in mind,” he adds. Elaborating on his point, Pasha says, “People keep fretting about arches and windows but not many care about what is happening inside.

He goes back to referring Kahn and adds, “When you are designing a building there is a lot of noise and excitement. When the building is being constructed, it is also very excited about being constructed and everyone listens to it. Once the building is in servitude nobody listens. Again, when the grass starts growing out of its foundation, it tells a story and people are eager to listen. If you go to Takhtbai or Taxila today, you can read in to their story because of the scales and units.”

One of the most iconic buildings Pasha has designed is the St. Thomas Church in Islamabad. “In terms of a religious building like a church or a mosque, the orientation is fixed,” he says, pointing out how the architectural language in this part of the world is still heavily influenced by the West which poses problems when constructing intelligently well-lit places.

“We have been taught by the English that north light is the best light so we have been following it blindly not realizing that in Lahore, Rawalpindi or Abbottabad the north tends to be absolutely dark. So the orientation depends on where you are. Our architecture, like our art, will eventually find its own niche language. May be not today or tomorrow but definitely in another 100 years. We are slowly but gradually defining our own identity in architecture.” Pasha concludes.

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ