Pakistan’s economic performance

Pakistan needs fresh industrial policy that will push for higher productivity

KARACHI:A snapshot of Pakistan’s performance in the 73 years since its independence reveals that the country has made significant progress on various socio-economic indicators.

It has shown considerable improvement in life expectancy, reduced infant mortality, boosted exports and enhanced income levels. However, when we compare Pakistan’s performance with other countries like India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Malaysia, we realise that Pakistan has not only lagged behind other Asian economies but has also trailed in terms of the rate of progress on these indicators, presenting a gloomy picture vis-a-vis its regional competitors.

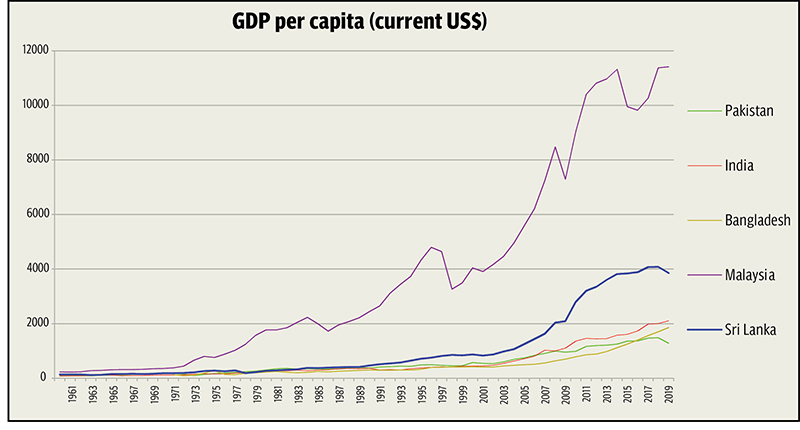

GDP per capita

GDP (gross domestic product) per capita is a useful statistic to measure a country’s standard of living. It is calculated by dividing the country’s economic output by its total population.

The GDP per capita of Pakistan and India was nearly the same in 1960 with Pakistan being slightly (1.4%) higher. However, the gap has now increased to 39% with India quite ahead.

Pakistan’s GDP per capita increased 15 times from 1960 to 2019 whereas that of India, Malaysia and Sri Lanka increased 26, 49 and 27 times respectively.

The gap in GDP per capita of Pakistan and Bangladesh was 34% in 1971 with Pakistan clearly enjoying a much higher standard of living. However, now the tables are completely turned with Bangladesh being ahead of Pakistan with a gap of 31%.

Exports

Exports not only improve balance of payments but are an important source of foreign exchange earnings. Although Pakistan’s exports have increased 105 times since 1960, it lags behind India and Malaysia whose exports increased 325 and 234 times respectively.

Bangladesh’s total exports increased by 84 times since 1971. Sri Lanka is the only country that remained behind Pakistan with an increase in exports of 46%.

The percentage of exports in terms of GDP is an insightful measure to look at international competitiveness.

A country may be able to sell its products domestically even if they are of poor quality because of the favourable treatment or excessive protection. But to sell internationally, its products must be of high quality for the world to purchase from it.

Pakistan’s weak position in terms of international competitiveness is clear from the fact that its exports comprised 10% of GDP as compared to 19%, 15%, 65% and 23% for India, Bangladesh, Malaysia and Sri Lanka in 2019.

India and Bangladesh surpass Pakistan even in terms of the rate of increase in exports-to-GDP ratio, which portrays further deterioration in terms of international competitiveness vis-a-vis these two countries.

Pakistan managed to increase its exports as a percentage of GDP by 1.44% since 1960 while India’s increase was calculated at 4.18% during the same time period. Bangladesh’s increase since 1971 has been 2.44%.

Infant mortality, life expectancy

The benefit of economic growth is a higher standard of living, leading to more resources for areas like health. Healthy populations then live longer, are more productive and save more.

Two important health indicators generally looked at by development economists are life expectancy at birth and infant mortality rates. Pakistan has shown considerable progress in terms of both these indicators, however, its rate of improvement has been much slower than other countries.

For example, Pakistan’s life expectancy was higher than that in both India and Bangladesh in 1971, however, Pakistan now lags behind these countries.

Pakistan’s life expectancy at birth in 2019 stood at 67.5 years as compared to 68.7, 72.4, 76.1 and 76.9 years for India, Bangladesh, Malaysia and Sri Lanka respectively.

Pakistan managed to reduce its infant mortality rate (per 1,000 live births) by one-third from 186 (per 1,000 live births) in 1960 to 60 (per 1,000 live births) in 2019.

Bangladesh and India have infant mortality rate of 26 (per 1,000 live births) and 31 (per 1,000 live births) respectively. Malaysia and Sri Lanka are way ahead with infant mortality rates of 6 and 7 (per 1,000 live births) respectively.

The above comparison of socio-economic indicators raises serious concern over Pakistan’s model of growth.

The economic policy debate has mostly been geared towards short-term perspectives of boosting exports through devaluation/ exchange rates and subsidies rather than focusing on the chronic issue of slow productivity growth.

Expanding exports through such a model may have brought some relief in the trade deficit but it has definitely eroded Pakistan’s international socio-economic position when compared with other Asian economies.

Way forward

In Pakistan, the term international competitiveness has often been wrongly understood as price competiveness. It is this view that policymakers and politicians have in mind when making economic and trade policies and boasting of increased exports.

REER (real effective exchange rate) and ULC (unit labour cost) are the most commonly used measures for analysing price competitiveness.

If this was to be considered a justified definition of international competitiveness, then a rise in ULC or stronger currency should lead to a decline in international competitiveness. However, empirical studies show that over long term, the market share of exports and relative unit costs or prices tend to move together.

Pakistan needs a fresh industrial policy that would take the focus away from short-term economic relief measures and push its ailing industrial base towards higher productivity and value addition.

Seeking to enhance exports through devaluation, exchange rate and protection is dangerous as it makes industries sluggish and inefficient and reinforces their focus on cost rather than producing better-quality products.

A classic example is Pakistan’s textile industry which, in spite of a long history of incentives and relief packages, still concentrates on low-priced commodity products. It has failed to come out of low skills and low competence trap.

To date, Pakistan hardly has any institute of even national repute that is producing relevant human resources for this industry that constitutes 60% of total exports. If Pakistan wants to remain competitive in its region, it must enhance its productivity growth by improving the quality of its industry-specific workforce.

Secondary education should be accompanied by the expansion of vocational training to improve specialised skills for export-oriented industries. Curricula should be developed with input from appropriate industry associations to ensure that relevant skills are developed.

This will not only enhance Pakistan’s productivity growth but will also provide a good alternative for its bulging youth that cannot acquire academic education for their working careers.

There is an urgent need for a linking mechanism that would closely work with ministries of education, labour and science and technology and coordinate the education and training requirements of its industrial development strategy.

The writer is a faculty member and ex-chairperson of the Economics and Finance Department at IBA, Karachi

Published in The Express Tribune, September 14th, 2020

Like Business on Facebook, follow @TribuneBiz on Twitter to stay informed and join in the conversation.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ