The psychoanalysis of Pakistan

If nations are like people, then what sort of person would Pakistan be? And what if that person were to see therapist?

Pakistan lay on the couch, with the therapist sitting behind him close to the door. She dimmed the lights, giving the weathered wood paneling a bronze glow. She hadn’t known Pakistan for long, but long enough to detect a disturbing pattern. Having changed several therapists, Pakistan followed a predictable course with all of his previous shrinks — starting off in a blaze of intimacy, slowly withdrawing, reaching a point of violent confrontation and then starting over with someone else. She knew that he badly needed her to understand him, even as he erected every possible obstacle in her endeavours to do so. Every session with Pakistan was a struggle — both for the therapist, as she tried to decipher his thoughts and motivations beneath the white noise of his obscurantist denial and obsessive paranoia — and for him, as he resolutely prevented her (and himself) from reaching his innermost chambers.

The therapist had no idea just how old Pakistan was, for even by his own accounts, his birth was a matter of great dispute. Pakistan was born either in the Bronze Age when the Indus Valley Civilisation was established in Mohenjodaro. Or, in the 8th century with the arrival of Muhammad bin Qasim, the 17-year-old Arab general, who became the first man to plant the flag of Islam in the Indian Subcontinent. Along the way, he also planted seeds in the collective Jungian psyche, the shoots from which continue to surface to this day. Sometimes he claimed to be born as a reactionary ideal in 1857. His real genesis, in 1947, was corroborated by an official birth certificate. Though that might simply be the day he was separated from his Siamese twin in a rather bloody operation.

The therapist took out her file to review her notes. From session to session, Pakistan varied from bouts of extreme pride and grandiosity– touting the mark on his forehead from excessive prostration during prayer, picking fights with the toughest boys in the neighbourhood, showing off the missile tattoos on his biceps — to states of despicable self-loathing — slitting his wrists to atone for his ‘sins’, claiming to have disavowed his religion and his brethren, shooting up heroin to disassociate himself from self-reflection. It was difficult to pin a diagnosis on him. Her initial hunch was that he had manic depression, swinging from grandiosity to doom and gloom. But she couldn’t pick that diagnosis, since these personality traits had persisted since about as long as the therapist could note. She relied on what she knew of Pakistan’s life thus far to inch closer towards a diagnosis.

Pakistan’s childhood remained of great interest to the therapist. While it was a topic that Pakistan refused to confront directly, drawing from his nightmares, his rambling digressions, and notes she had received from his previous therapists, a vague picture had come together. Born on the stroke of midnight, Pakistan and his twin brother, India, had had a tumultuous childhood, resulting in frequent fights, bleeding noses and cut lips. Orphaned in his infancy with the premature death of his father, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, frequently beaten by his estranged brother (who also took away Pakistan’s favourite cashmere sweater), deeply insecure due to his short stature, and lacking any sort of guiding hand, Pakistan had a tormented upbringing. Once he attacked his brother to take back his sweater but failed (though he still claims it was his brother who started that particular round of fisticuffs). To this day, Pakistan refused to acknowledge any blood relationship with his brother, claiming to be a separate entity from him.

After his companion and childhood friend, Bangla, abandoned him in the early ‘70s, instead of reflecting on the many years of neglect and abuse he had inflicted on her, Pakistan transitioned into another high of energy. His charisma won him many friends and he formed a relationship with a mysterious sheikh, who would go on to have a deep impact on him. Sheikh Al-Wahab charmed Pakistan with his white robes and his shiny Rolexes (which he would jingle whenever he wanted Pakistan’s attention). The therapist could see that Pakistan believed that the sheikh, and his devout breed of Islam, offered him a chance to reconstruct his identity … but it was a dangerous façade.

Armed with this new identity, Pakistan entered a phase of gradual psychological self-mutilation, wherein he began to erase all memories that contradicted his new self. He grew a beard, rode his pants high on his tummy and learnt Arabic, but forgot his own native tongue. In his attempt to be born anew, he began to loathe himself: his brown skin, the festivals he celebrated, and the culture he shared with his estranged brother.

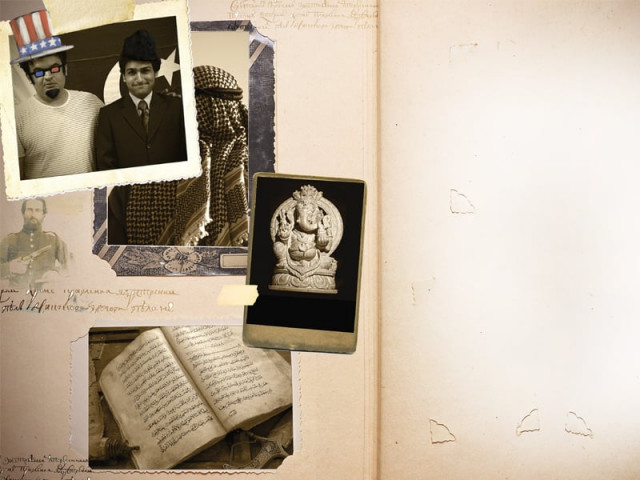

Pakistan’s newly found religiosity didn’t go entirely unnoticed. In fact, Uncle Sam encouraged Pakistan’s violent streak in order to settle a score against its long time adversary by training Pakistan’s crazy cousin, Talib. With his AK-47 loaded with incendiary rounds and an even more incendiary faith, Talib, with the help of his Arab roommate, Qaeda, and Pakistan’s full backing, did for Uncle Sam what no one else could have. After the fight, when Pakistan and Talib turned around to celebrate their victory with a series of high-fives and ‘Allah-u-Akbar’ chants, Sam was nowhere to be found. All they had to show for their efforts was a crate full of Kalashnikovs, heads full of grandiose delusions and a stash of smack to ensure insight remained an unwanted guest.

Pakistan, far from smothering Talib’s zeal, channeled it to settle scores with India in his unending struggle to regain his cashmere sweater. But in his efforts to agitate Talib against India, it was Pakistan who was influenced by his oddly appealing cousin. Meanwhile, Qaeda ran out of his supply of Ritalin® and, no longer in the spotlight, grew increasingly bored in his suburban house-cave. Convinced that Sam, who no longer showered him with attention, was the root of all the evils in the neighborhood, Qaeda went to Sam’s house with his bamboo stick and poked it right into Sam’s eye. Sam, infuriated, attacked Qaeda, who had taken refuge in Talib’s house-cave next to Pakistan’s, and demanded of Pakistan that he too join him in fighting both Qaeda and Talib. Scared out of his wits by the heavily muscled and belligerent Sam, Pakistan shaved his beard and donned a suit to convince Sam that he was ‘with him, not against him’. But in his heart, Pakistan could not abandon Talib, and banking on Sam’s short attention span (possibly due to serious ADHD), hoped to be able to hold off any Public Displays of Affection with Talib until Sam’s interest fizzled out.

But Talib just didn’t get it. He began to attack Pakistan for supporting Sam. Talib and Qaeda dealt Pakistan blows the likes of which he had never received, tearing into him, ripping apart whatever was important to him. But for all the pain they inflicted on him, Pakistan blamed everyone else in the neighborhood. Unable to remove himself from his association with Talib and Qaeda, and yet fully aware of their actions, the therapist noted that Pakistan found himself more confused, more in pain, more depressed and more vulnerable, than ever before.

The therapist formulated Pakistan’s history into what she regarded as a pattern of unstable identity, unstable relationships and fearful attachments. She started crossing out all the different diagnoses she had written on her sheet including adjustment disorder, substance abuse, depression with psychotic features, dysthymia and anti-social personality disorder, until the only diagnosis un-maimed by her pen was borderline personality disorder.

And yet, even armed with this knowledge, the therapist continued to have a difficult relationship with Pakistan. She knew that this was not just because Pakistan was, to put it mildly, un-normal, for she barely knew anyone in the entire neighbourhood who was.

“What happened, Pakistan? You look terrible.”

Pakistan remained mum, looking blankly up at the ceiling. The therapist prodded on, “Why do you have mud on your hands?”

“A great flood destroyed my house. I had to dig myself out of the rubble. My cow, Rani, my princess, I couldn’t find her. The waters took her away. My crops have all run a-waste.” Pakistan spoke in a monotone, staring blankly at the ceiling. The therapist didn’t know what to feel. A part of her believed he was pre-schizophrenic, his ability to process reality crumbling slowly. Another part felt that the heroin was like a virus, forever impairing his ability to test reality. She tried to feel sympathy for him, but found herself unable to do so. “Did anyone help you out?”

“Sam helped me out, not because he cared, but because he feared that if I lost my mind a bit more, I would blow up in his face.”

The therapist carried on, without believing his entire flood story. Just a few years back he had come running to her, with an earthquake-story in which his house was leveled, and here he was again, carrying on what was now becoming a comically long list of tragedies, some real, some imagined. “Why do you think these catastrophes happen to you?”

“It is a test of my faith, or a punishment for my transgressions, I can’t seem to understand.” The therapist’s attempts at objectivity began to fail, as Pakistan’s contradictions started to amuse her. His misery became a source of mirth, rather than solemn reflection.

“What transgressions?”

“I have failed my religion and no matter how much I pray for forgiveness, Allah continues to punish me. And I continue to be Sam’s slave. I have shaved my beard and started wearing suits just so that he does not suspect me of being with Talib. But inside, I know that I am in the wrong, and that is why Allah-Almighty punishes me.”

“But haven’t these Muslim ‘brothers’, hurt you more than even those who you claim are your enemies, including your actual sibling? Look at how you’re bruised, scarred, hurt — isn’t that the work of your so-called brothers?”

“They are angry, and justified in being so.”

“So they have the right to spew hatred and commit violence, but no one else does? Why bend the rules for them? Your sheikh has taken more from you than even your worst enemies: he took away you.”

“What is that supposed to mean? I have me.”

“What me, Pakistan? What of you do you have left?” The therapist’s frail figure shook, her spectacles danced on the bridge of her nose, as she continued to unabashedly counter-transfer.

“All of me is here in front of you. Me, born to live life governed by the laws of Islam, and to vanquish the apostates who tarnish its name.”

“But how can that be! Don’t you remember that when you were born, not in the 8th Century, but in 1947, your first law minister was a Hindu, and your finance minister was an Ahmadi, a sect you now consider as worthy of murder!”

“That cannot be true! Why wouldn’t I remember it if it were so? Wait, you are right, but how…?”

The blank look left Pakistan. Suddenly, he was awash with palpable emotion. The therapist knew what was going on, a rock had been upturned, and from beneath it had scampered out a thousand repressed memories. Memories of a father who never said his prayers, who swore by his suit and his whisky, of a time when festivals were marked with kites flying in the sky rather than blood from sacrificial animals running in the streets. Clearly in pain, Pakistan held his head. He tried to get up from the couch, before falling onto his knees, his hands covering his ears, ensuring that nothing but the voice within was heard. The therapist ran to the door, but stayed on to look at Pakistan writhe as alarmed guards ran in to pin him to the ground. Her unfinished case history was still lying next to her chair in the room. She was shaking. This would be her last session with Pakistan not so much because Pakistan’s malady awoke no empathy in her anymore, but because she knew she had stepped on the wrong side of Pakistan’s split monochromic psychological spectrum of blacks and whites.

Pakistan’s search for reflection began anew; a search that he ensured was always a never-ending spiral, where the journey itself is enacted only to avoid the destination. The therapist wondered who Pakistan would be if she were to meet him after some time; she wasn’t even sure if she would recognize him. She held the notebook tightly next to her chest and walked off determined to hold on to her diagnosis, if nothing else. And yet, she knew that in spite of all that he had endured (and inflicted) he had still lived to tell the tale. A survivor and stubborn to the core, she knew he’d be back. And while he wouldn’t be pretty for his pains, she knew, irrationally, that she might just like to see him again.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, July 24th, 2011.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ