Himalayan glaciers melting twice as fast: study

Climate change is eating Himalayan glaciers, threatening water supplies for millions of people in South Asia: study

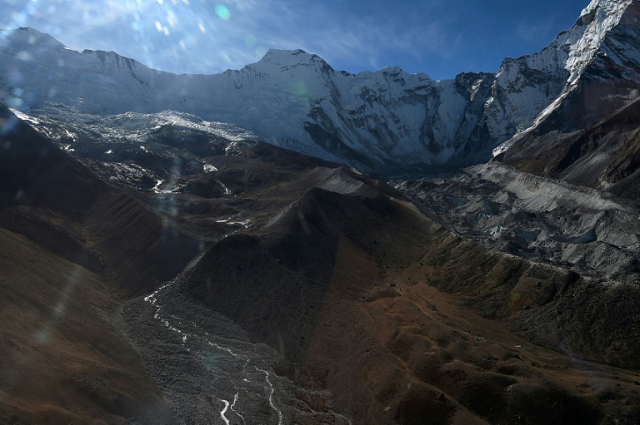

A glacier in the Everest region of Nepal pictured in November 2018 -- climate change is eating the Himalayas' glaciers, threatening water supplies for hundreds of millions of people downstream across South Asia. PHOTO: AFP

The study, which appeared in Science Advances on Wednesday, is the latest indication that climate change is eating the Himalayan glaciers, threatening water supplies for hundreds of millions of people downstream across South Asia.

"This is the clearest picture yet of how fast Himalayan glaciers are melting over this time interval, and why," said lead author Joshua Maurer, a doctoral candidate at Columbia University in New York.

Scientists combed 40 years of satellite observations spanning 2,000 kilometers (1,243 miles) across India, China, Nepal and Bhutan, and found that the glaciers have been losing the equivalent of a foot-and-a-half (45 centimeters) of ice each year since 2000.

Many of the 20th-century observations came from recently declassified US spy satellite imagery.

The figure is double the amount of melting that took place from 1975 to 2000.

Past research has found similar trends, but the latest work is bigger in its geographic and historic scope.

It concluded that rising temperatures are the biggest factor.

Though temperatures vary from place to place, average temperatures were one degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) higher between 2000 to 2016 than they were between 1975 and 2000.

Other factors the researchers blamed were changes in rainfall, with reductions tending to reduce ice cover, and the burning of fossil fuels which lead to soot that lands on snowy glacier surfaces, absorbing sunlight and hastening melting.

"It shows how endangered (the Himalayas) are if climate change continues at the same pace in the coming decades," said Etienne Berthier, a glaciologist at France's Laboratory for Studies in Geophysics and Spatial Oceanography, who was not involved in the study.

Sled dogs wade through standing water on the sea ice during an expedition in northwestern Greenland, whose ice sheet may have completely melted within the next millennium if greenhouse gas emissions continue at their current rate, a study has found. PHOTO: AFP

Sled dogs wade through standing water on the sea ice during an expedition in northwestern Greenland, whose ice sheet may have completely melted within the next millennium if greenhouse gas emissions continue at their current rate, a study has found. PHOTO: AFPA separate study also published Wednesday found Greenland's ice sheet may have completely melted within the next millennium if greenhouse gas emissions continue at their current rate.

The Greenland ice sheet holds the equivalent of seven meters (yards) of sea level.

"If we continue as usual, Greenland will melt," said lead author Andy Aschwanden, a research associate professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute.

It is the most recent warning about warming in the world's coldest regions.

"What we are doing right now in terms of emissions, in the very near future, will have a big long-term impact on the Greenland ice sheet, and by extension, if it melts, to sea level and human society," Aschwanden said.

The study, which used data from NASA's Operation IceBridge airborne campaign and was published in Science Advances, is the latest to suggest a much greater rate of melt than was estimated by older models.

The model relies on more accurate representations of the flow of "outlet glaciers," river-like bodies of ice that connect to the ocean.

"Outlet glaciers play a key role in how ice sheets melt, but previous models lacked the data to adequately represent their complex flow patterns," NASA said in a statement about the study.

"The study found that melting outlet glaciers could account for up to 40 percent of the ice mass lost from Greenland in the next 200 years."

As ocean waters have warmed over the past two decades, they have melted the floating ice that once shielded the outlet glaciers.

As a result, "the outlet glaciers flow faster, melt and get thinner, with the lowering surface of the ice sheet exposing new ice to warm air and melting as well."

In the next 200 years, the ice sheet model shows that melting at the present rate could contribute 48 to 160 centimeters (19 to 63 inches) to global sea level rise, 80 percent higher than previous estimates.

In October, the UN's Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) reported that avoiding global climate chaos will require a major transformation of society and the world economy that is "unprecedented in scale," and warned time is running out to avert disaster.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ